HMRC claws back celebrities' tax profit on empty data centres

- Published

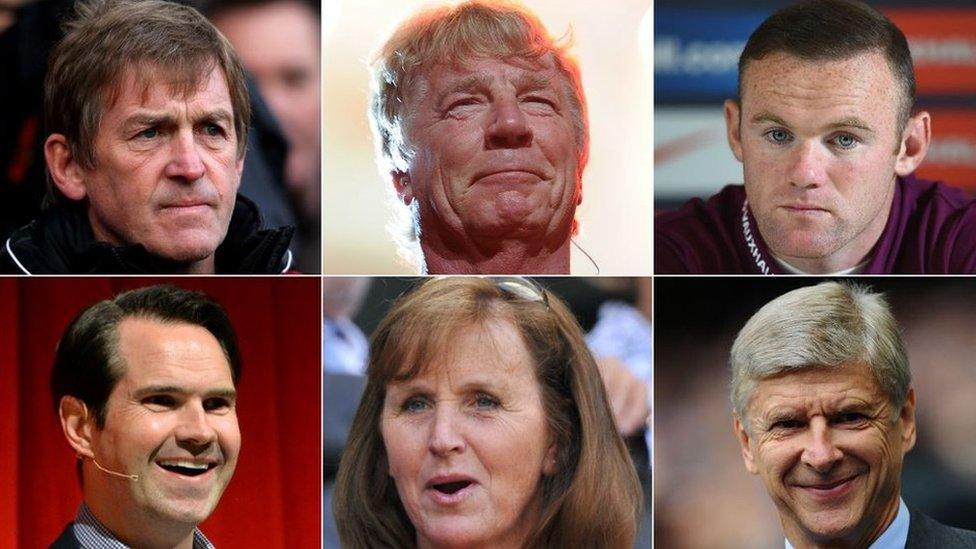

Investors and former investors in Cobalt Data Centres 2 and 3 included a number of celebrities and household names, such as (clockwise from top left) Kenny Dalglish, Rick Parfitt, Wayne Rooney, Arsene Wenger, Lady Ann Redgrave, Jimmy Carr

Millions of pounds in tax relief given to celebrities via a scheme to start economic growth in deprived areas is being clawed back by officials.

Wayne Rooney, Arsene Wenger, Jimmy Carr and Rick Parfitt were among 675 people who invested £79m in 2011 but got back £131m in relief - or £50m "tax profit".

Their money built two data centres on Tyneside that remain unused, despite assurances marketing began in 2013.

Project backers Harcourt Capital said it expected its first tenants soon.

There is no suggestion of wrongdoing by anyone who put money into Cobalt Data Centres 2 and 3, nor that they were aware they would not be tenanted and functioning within a reasonable time.

Some investors have had tax payment demands, the BBC understands.

Generous tax allowances

These accelerated payment notices (APNs) - requiring an individual to pay first and appeal afterwards if they disagree - are issued by HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) if it believes too little tax has been paid.

Harcourt Capital said HMRC began an inquiry into the centres in 2012 but did no work on it until 2015. Some investors had been "forced" to fight HMRC demands for payment of tax and had taken the matter to tribunal and court, it added.

HMRC said it could not comment on individual cases.

The Cobalt Data Centres have elevated security including double fencing and mantraps and lie within sight of major companies, council offices and government departments

The investors benefitted from generous tax allowances - intended to encourage economic growth in enterprise zones - just before these allowances were scrapped in April 2011.

These allowed them to claim 50% tax relief on the full £263m cost of building the data centres, despite their contribution being £79m. The remaining 70% of the cost was borrowed from Bank Winter in Vienna.

It means many investors received more money in tax relief than they actually paid in.

Investors contributed an average of £117,000 each, though the exact proportion is not clear. As a group they made a "tax profit" of about £50m.

This allowance - of about £74,000 each - could then be deducted from future tax bills.

Who invested in the data centres?

Cobalt Data Centres 2 and 3 have never had tenants

The data centres are surrounded by lawn and leafy trees within sight of major companies, council offices and government departments on Cobalt Business Park on North Tyneside.

They were marketed as shells, poised to house computer servers belonging to whoever needed somewhere to put them.

A list of promised specifications included a dedicated power supply from the National Grid and security measures such as mantraps - a vestibule with two set of interlocking doors, rather than anything more brutal.

Footballers, celebrities, lawyers, accountants, doctors, dentists, board members of well-known businesses, millionaires and people involved in banking and finance were among the 675 investors.

Household names involved include Kenny Dalglish, Roy Hodgson, Terry Venables, Marouane Fellaini, Lady Elizabeth-Ann Redgrave, Arsene Wenger, Oscar-nominated producer of Harry Potter films and Gravity, David Heyman, and co-owner of T in the Park and V Festival, Simon Moran.

Comedian Jimmy Carr, who was criticised in 2012 for sheltering income using the legal but aggressive K2 tax avoidance scheme, resigned as a member of Cobalt Data Centre 2 in May. His agent has not responded to requests for comment.

Representatives of Wayne Rooney, Marouane Fellaini and David Heyman declined to comment.

Rick Parfitt's principal consultant said: "As this matter is currently under appeal it would be inappropriate to comment at this time."

Dr Redgrave said she had invested "in good faith on the advice of my financial advisor through an investment scheme".

The agent of Roy Hodgson and Arsene Wenger said his clients were "pleased to invest in government-backed regeneration programmes which will hopefully help to generate new jobs in these areas".

Mr Dalglish, Mr Venables and Mr Moran have been approached for comment.

The data centres are now being marketed under the name Stellium Datacenters.

Two of the new company's three directors - Piet Pulford and Guy Marsden - are both original investors in the data centres and directors of the buildings' developer.

Project backer Harcourt Capital said the delay in letting the centres was because of a rapidly-evolving industry which had proved a "more difficult market to predict than was originally expected".

Harcourt said HMRC, by challenging enterprise zone investments, "appears to now be backtracking" on agreements made with industry in the 1990s on how enterprise zone schemes should comply with legislation.

"We are seriously concerned that HMRC's actions are treating investors who fundamentally supported successive governments' efforts to successfully regenerate derelict areas of the country extremely unfairly," it said in a statement.

This was "creating considerable stress and financial burdens on individual taxpayers", it said.

Was it exploited?

Investment in the centres attracted criticism when it was highlighted by The Guardian newspaper in 2013., external

The paper quoted Margaret Hodge, then chair of the Commons public accounts committee, as suggesting their lack of tenants "fuelled the perception that the scheme was aimed at tax avoidance".

At a meeting of the Commons public accounts committee last week, Houghton and Sunderland South Labour MP Bridget Phillipson asked representatives of HMRC what progress had been made since then.

"It's unfair potentially on those people if it is a legitimate means by which you can - and should - invest, but it's not fair on the taxpayer if it takes a long time for HMRC to get to uncover quite what's going on," she said.

There was a "principle at stake" if a system set up to support regeneration and investment was "exploited by others with no interest in regeneration or investment, simply to line their own pockets", she added.

Chief executive Jon Thompson said HMRC would try to send a detailed update to the committee.

Labour MP Bridget Phillipson asked the HMRC about delays and investors "lining their pockets"

A spokesman for HMRC separately stressed that, although "morally reprehensible", tax avoidance was neither tax evasion nor illegal.

"It often involves contrived, artificial transactions that serve little or no purpose other than to produce a tax advantage," he said.

"It involves operating within the letter - but not the spirit - of the law."

HMRC has warned against promoters marketing those schemes, external as "wealth management products or dressed up as exciting investment opportunities".

Analysis: Kevin Peachey, BBC personal finance reporter

While tax has never been simple, the difference between tax evasion and avoidance has always been clear.

Evasion is illegal - dodging taxes by failing to fully declare earnings and income. Avoidance is legal, used to reduce taxable income. There is also legitimate tax planning, using government tax reliefs such as saving in an ISA.

But now the government and the UK's tax authority spend a lot of energy attempting to tackle "aggressive avoidance". That is bending the rules to gain a tax advantage that Parliament never intended.

HMRC issues fines not only to individuals failing to pay this tax, but also the advisors and promoters in the background.

That is not easy when information and money can now move around the world very fast. Yet critics say the UK's tax authority is too far off the pace to satisfy the honest taxpayer.

'Too good to be true'

Richard Murphy from Tax Research UK, which campaigns on tax issues, said avoidance was "tax abuse".

"The boundary between avoidance and [unlawful] evasion is simply too imprecise to be of any practical use in the management of taxpayers' affairs," he said.

In cases where investors can claim tax relief on more than they put in, there was "quite clearly a mismatch", he added.

John Bramhall, deputy chief executive of the Professional Footballers' Association (PFA), said it had warned players against schemes which look "too good to be true" - but they had trusted their financial advisors.

"They're professional footballers, they look to these people to give them specialist advice," he said.

- Published1 November 2016

- Published17 August 2016

- Published5 April 2016

- Published12 May 2014

- Published26 April 2013

- Published21 June 2012