Atelier Populaire: French protest art found in English castle

- Published

Publisher's son Oliver Dobson found the originals among - literally - tonnes of books and papers

A stash of original French political art has been found in the cellar of an English medieval castle.

The posters were found in Brancepeth Castle in County Durham, tucked away among books belonging to the late publisher Dennis Dobson.

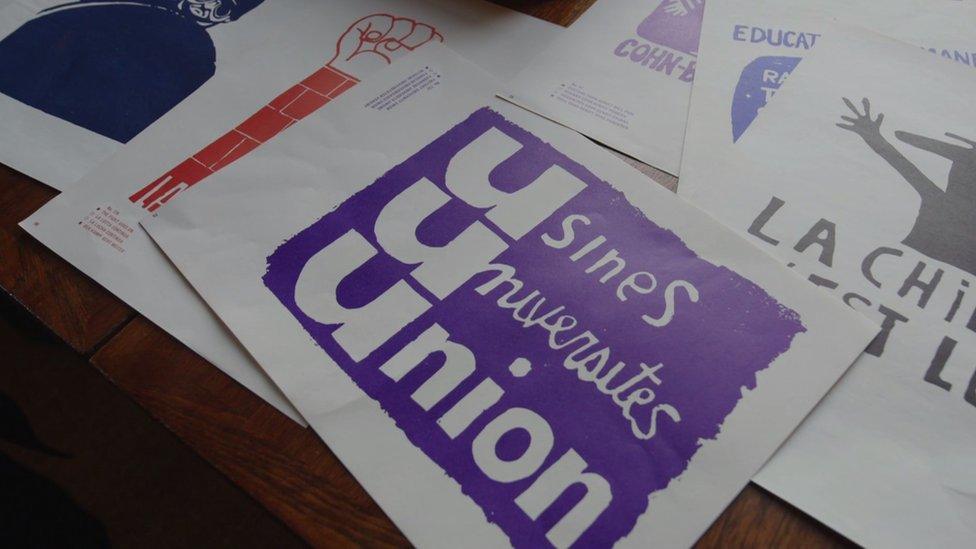

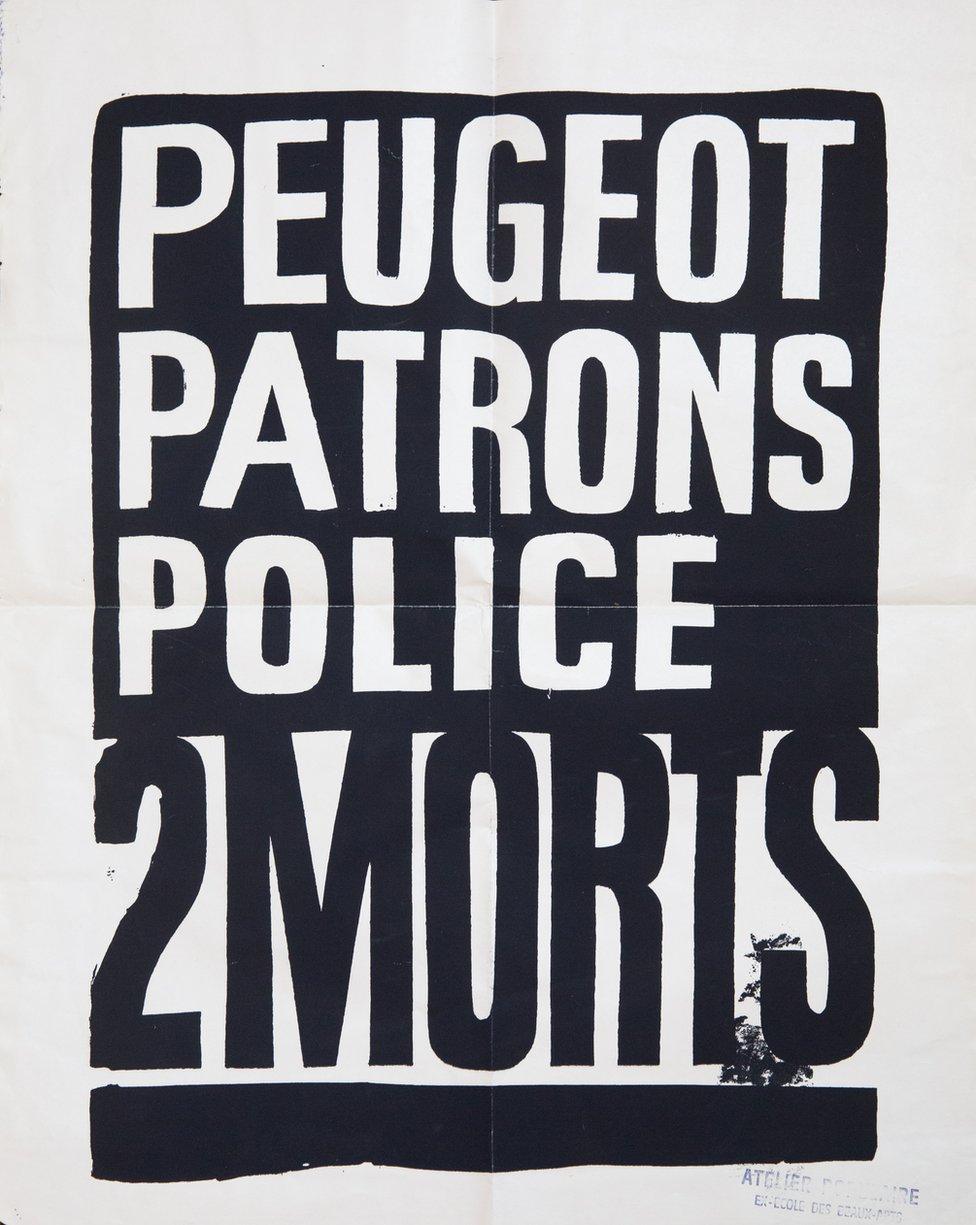

They were produced in 1968 by a group of Parisian students protesting against the "bourgeois" university system, the government and the "police state".

French expert Dr Gillian Jein says their discovery is "overwhelming".

"They're amazing - I can't believe the colour is so vibrant," she says.

Similar posters - originals rather than prints - can fetch up to £1,500, depending on rarity and condition.

The stable temperature in the old castle wine cellar has helped preserve the posters

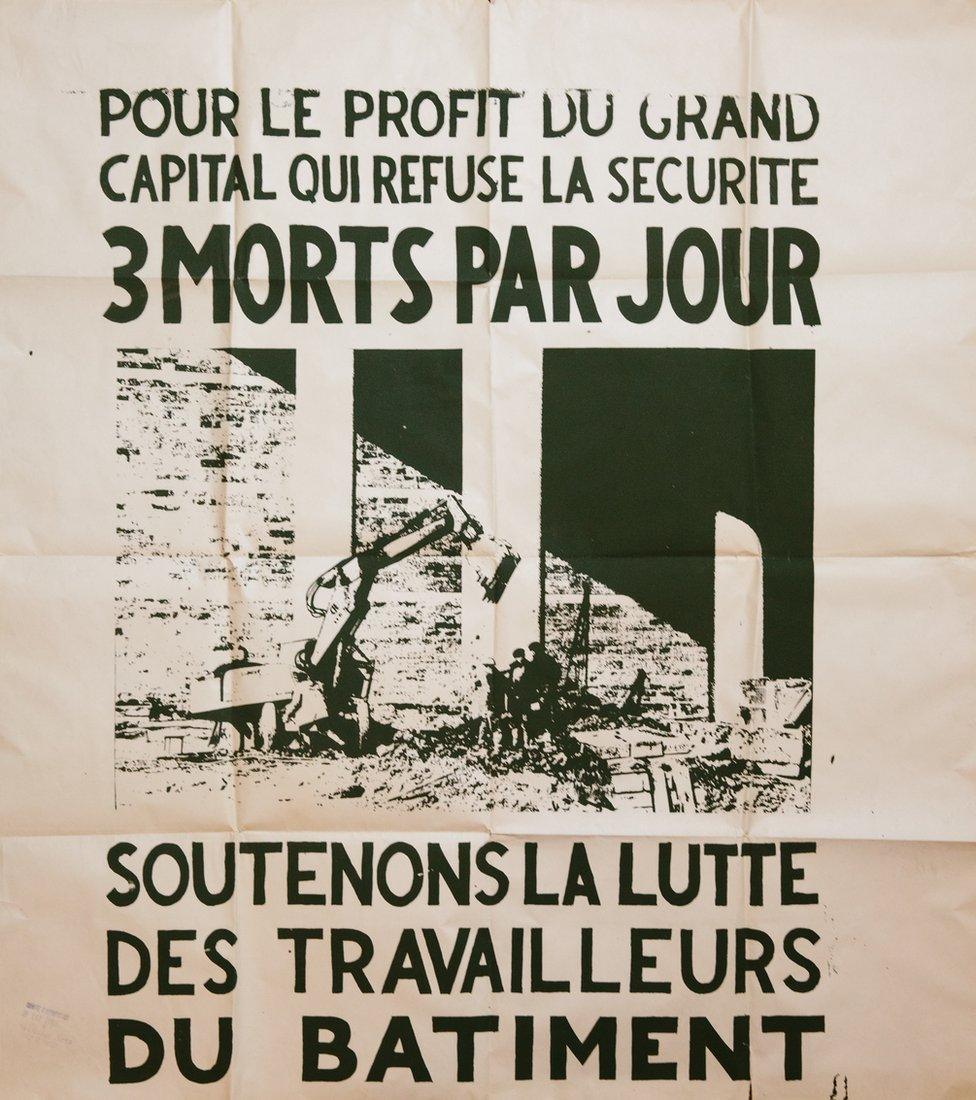

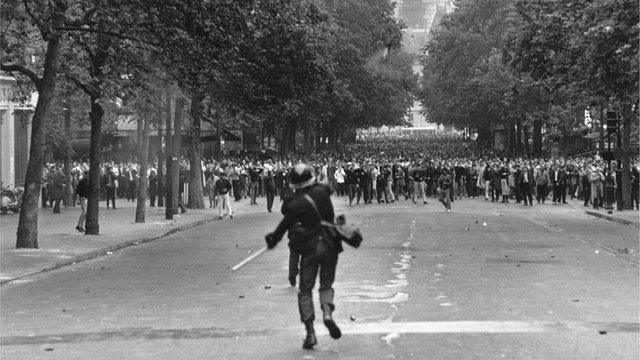

The protests of May 1968 began with students objecting to the policies of President Charles de Gaulle.

The confrontation escalated to involve factory workers and, at one point, saw a million people march through Paris demanding his resignation.

One group of art students from the École des Beaux-Arts founded the Atelier Populaire - or people's workshop - and printed posters to spread the revolutionary message.

Many of the posters poked fun at political figures such as Charles de Gaulle with a caricature nose and trademark military kepi

The posters were minimalist, condemning capitalism, the state and police "repression".

Many poked fun at political figures, including Charles de Gaulle himself, with his "military kepi, the big nose, the arms out", says Dr Jein, a senior lecturer in French studies at Newcastle University.

"It was art on the streets in the service of the people," she says.

Daniel "Red" Cohn-Bendit - once a student leader, now member of the European Parliament

The students planned to sell their first poster to a gallery to support striking factory workers, Dr Jein says.

But some others "grabbed it from their hands and pasted it on the walls", she says.

"They realised, forget galleries, we need to put these messages on the walls."

The students quickly realised the posters would be more effective on walls than in galleries

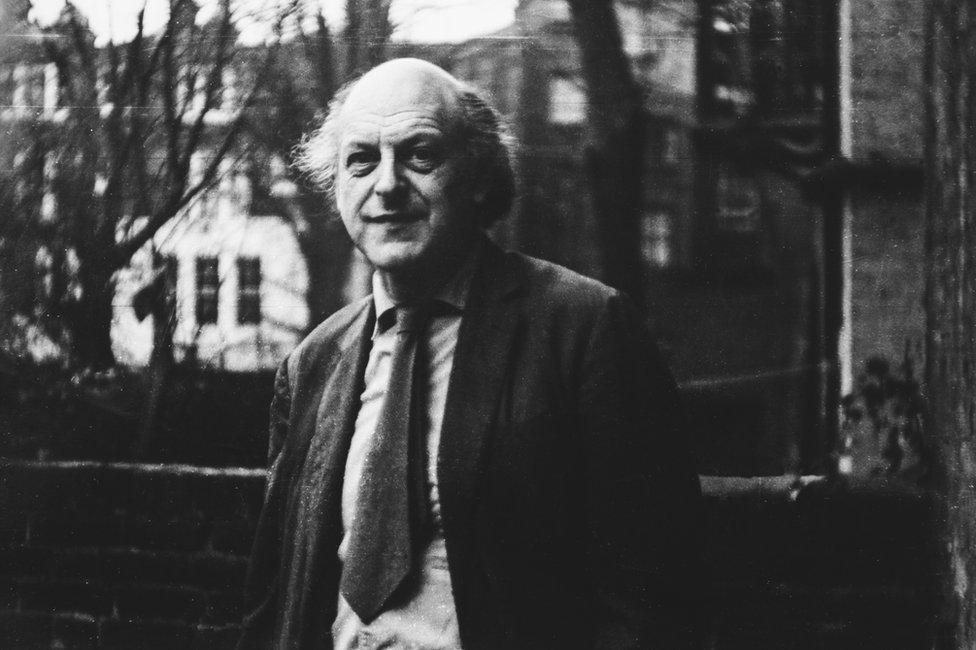

They were introduced to Mr Dobson by a literary agent friend living in Paris, says his son, Oliver.

"I found a letter that indicates she saw dad as being suitable for the Atelier Populaire, for the artists, because he produced lovely books and so he would do them justice and also have a sympathy for them," he says.

His father had something of a socialist "leaning" and had already raised funds for republicans in the Spanish Civil War.

So the students came to the family home and office in London.

"My sister remembers them all gathered round, Gitanes and all the rest of it, sitting there, discussing what to do," the younger Mr Dobson says.

His son says Dennis Dobson was "perhaps the most conservative of socialists you'd ever meet"

The poster production was "all very clandestine" as sticking them on walls in France was prohibited.

"Back in '68 they were doing this illegally, effectively, by occupying the school and just running off posters that were hand printed from silk screens on paper that was donated to them by the newspaper workers who were on strike," Mr Dobson says.

The posters were printed on newsprint donated from striking newspaper offices

Dennis Dobson's attention to detail was such that he had the book printed using pre-mixed ink - to match the original posters' own silk-screen printing process - rather than the usual book-printing method of layering blue, red and yellow over one another to produce the desired colour.

The book became so big it would not fit into a binding machine, so every copy had to be bound by hand.

Dr Gillian Jein says she "could not put a price tag" on the posters

Original prints, destined to be framed and hung on walls, are now sold for hundreds of pounds. Copies can be picked up in markets and shops.

However, a note in the front of the book stresses the posters should only be used for "the furtherance of the revolution" and as "items of protest", not for "bourgeois pleasures" as pieces of art, Mr Dobson says.

"But the only way they could disseminate the information was to make sure it got out there," he says.

"I think they probably realised that you had to use every route to market."

The student backlash against the establishment spread to teachers and factory workers

The Dobson family bought Brancepeth Castle in 1978 but, just before they moved, Mr Dobson died on a train home from the Frankfurt book festival.

His wife, Margaret, transported their seven children and about a quarter of a million books from London alone.

She stored much of this publishing legacy in the 700-year-old castle's cellar, including first editions of children's classics such as Mr Benn and Elmer.

It stayed largely untouched for 30 years.

The trucks bringing the vast collection to Brancepeth only just made it through the gates

The family knew the book of French protest posters was among the hoard but had no idea Mr Dobson had kept four originals among the many less-valuable prints.

These were only discovered when, expecting a visit from a BBC film crew interested in the story of the book, Oliver Dobson started rooting around.

"Just pure serendipity, hunting through baskets, I came across a wrapped up brown parcel and, in it, was the Atelier production files," he says.

About a quarter of a million books were brought from the Dobson home and offices in London

What will happen to the posters, how they might be made available to view or used to mark his parents' work, is still under family discussion.

You can see more on this story on Inside Out on BBC One in the North East & Cumbria on 11 February at 19:30.

The children were enlisted to clean out the wine cellar ready for the collection

- Published28 April 2018

- Published18 May 2016

- Published3 September 2011