Lady Tankerville: The botanist and secret scientist

- Published

Lady Emma Bennet, painted with two of her 11 children, lived from 1752 to 1836

Lady Emma Bennet was an 18th Century aristocrat and plant enthusiast whose collection of botanical paintings is a jewel of the Kew Gardens archives. Despite the great effort that goes into preserving her collection, little was actually known about the botanist and secret scientist until a historian started to do some digging.

In 1932, several crates were delivered to the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, London, after being bought at auction from a castle estate sale.

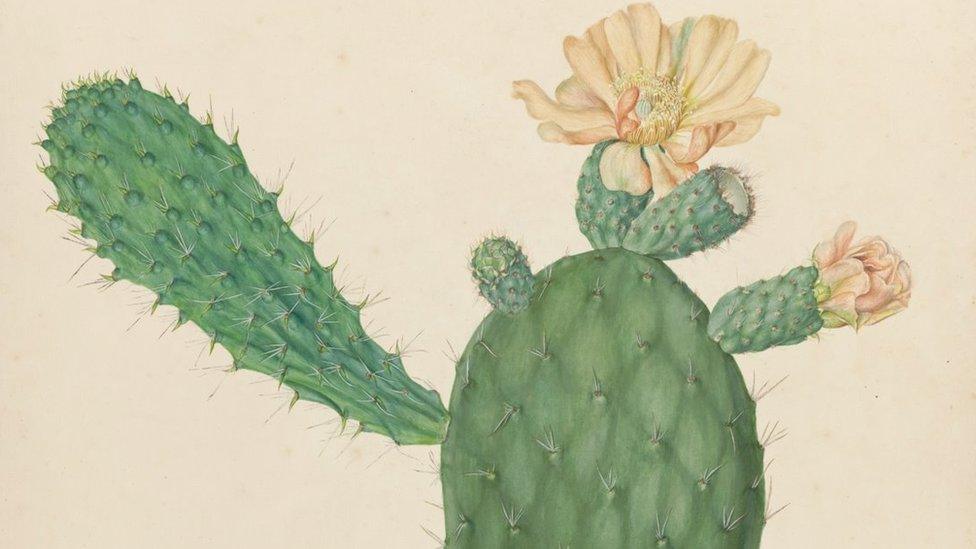

They contained 648 watercolours of plants and flowers amassed some 130 years previously by Lady Emma Bennet, the fourth countess of Tankerville.

The illustrations are fragile. They are painted in gouache and watercolour on vellum, which had then been fixed to paper in an album, a customary method in the 18th Century.

However, with the vellum's flexibility and the paper's rigidity, there is a high risk of paint detaching from the vellum.

Lady Emma Bennet amassed 648 images of her beloved plant collection including some she painted herself

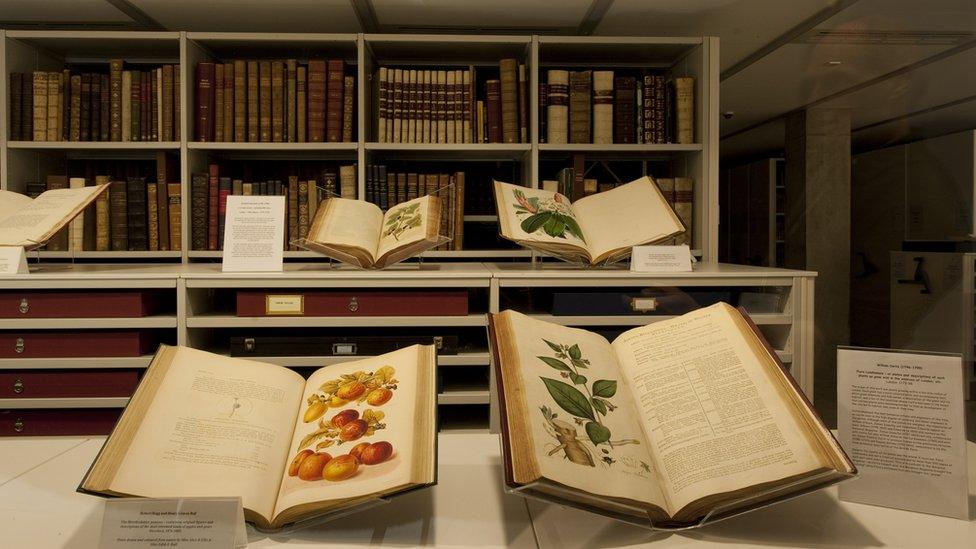

Carers of the collections have worked to preserve them, placing them in Kew's Rare Books and Illustrations store where they must be kept at a safe and steady relative humidity and temperature to avoid further damage.

Kew knew the paintings were special and needed preserving for further research, but it wasn't until 2019 when a mature history student from Northumberland visited that their secrets began to be revealed.

June Watson, now 75 and studying for a PhD in the forgotten women of 18th Century science, came across Lady Emma while writing a book on her own family history.

June Watson has been researching Lady Emma Bennet

For some 200 years, June's family were the stewards for the Aubrey family and their home at Dorton House in Buckinghamshire.

Lady Emma's sister Mary married into the Aubrey family which brought her to the attention of June.

Lady Emma was born in 1752 and after the early deaths of her parents she and Mary were raised on a country estate in Surrey and a city square in London by their rich uncle George Colebrooke, a banker and chairman of the East India Company.

At the age of 19 she was married to Charles Bennet, the fourth earl of Tankerville and owner of Chillingham Castle in Northumberland, a prominent MP and shell collector who later became one of the men who wrote the rules of cricket.

The Tankerville Collection is kept at the Royal Botanic Gardens along with numerous other rare and valuable books and documents

It was an arranged marriage but there was great love and admiration between the two, June said, perhaps evidenced by their 11 children born over a 16-year period.

It was the age of enlightenment when explorers were travelling the world, collecting rare and exotic species of plant to be both marvelled at and monetised.

Doctors wanted new medicines, clothing manufacturers new materials and food and drink makers new ingredients.

Lady Emma made notes to go along with her accurate illustrations

Carl Linnaeus devised the ultimate classification system by which all plants came to be categorised and collectors such as Francis Masson were commissioned to search the globe for intriguing new varieties.

Lady Emma was one of those who caught the plant collecting bug and was a friend of Joseph Banks, the naturalist who famously joined James Cook's Endeavour voyage to South America and Australia.

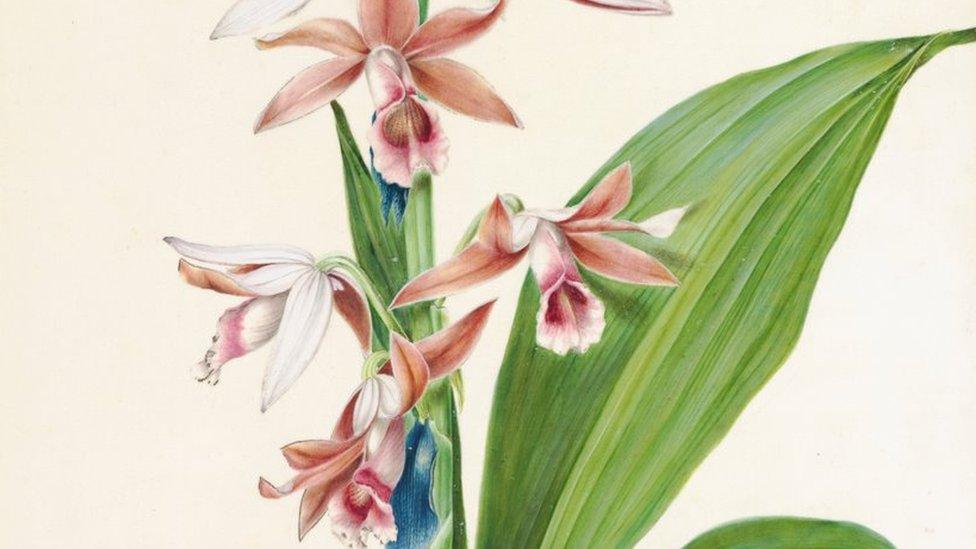

Banks, who bought and lived in the Soho Square house Lady Emma had grown up in as a child, was impressed by her passion and skill and named an orchid after her after she became the first person to successfully make it flower in England.

Joseph Banks named this orchid after Lady Emma as she was the first person to successfully make it flower in England

The Bennetts lived mainly at Walton House on the bank of the River Thames in Surrey, and it was there Lady Emma and her head gardener William Richardson experimented with cultivating new and exotic plants in the estate's greenhouses

But while plant collecting was seen as a "gentile and useful" past-time for wealthy and well-educated women according to Lynn Parker, Kew's curator of illustrations and artefacts, the actual science of botany was not something they were encouraged to pursue with women unable to attend university or join the Royal Society.

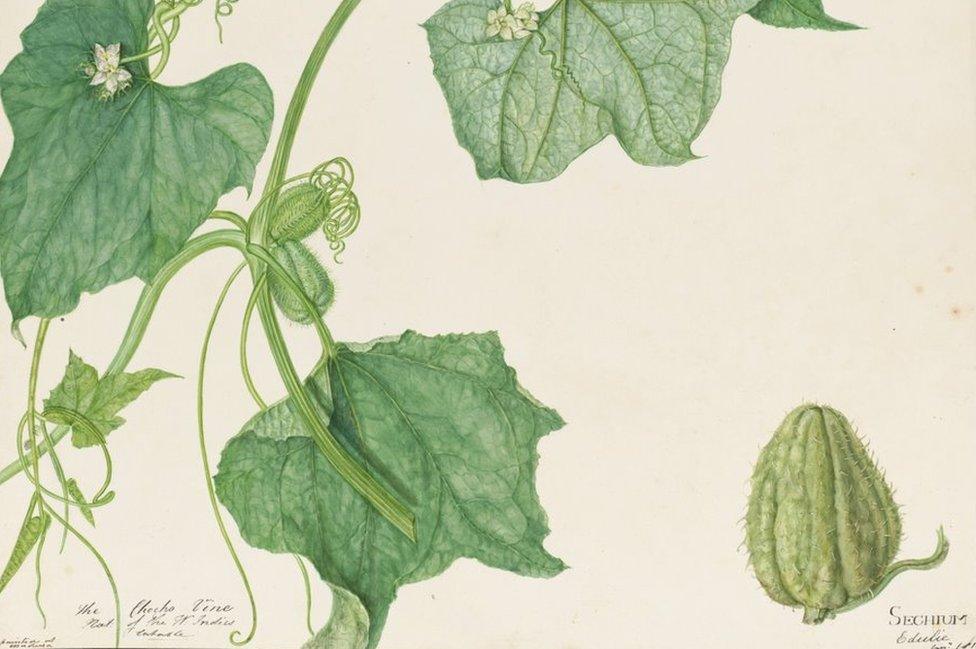

Lady Emma's paintings are exquisite in their detail, but what elevates them from artworks to being of botanical significance are the notes Lady Tankerville made on the margins and back, June said.

They are scientific in scope, detailing the plants' various classifications, conditions for growth, history and her own observations.

The illustrations are intricately detailed and Lady Bennet added scientific notes

Lynn agrees, adding: "On the face of it she is collecting flowers which was thought of as a respectable past-time, but she is also clearly interested in the science of them, such as where they are coming from and their anatomy."

In 1811 Lady Emma moved to Madeira, the Portuguese island off the coast of north Africa, on doctor's orders after two of her children became ill with consumption.

Madeira was a bustling trading port, a key meeting point on the sailing routes between the Americas and India, and its balmy climate was reckoned to be good for health of the ill.

During her 18-month stay, Emma painted 21 pictures of the island's plants which were added to the collection of those she had commissioned of her own plants.

They form the basis of an exhibition currently on display at Northumberland County Council's County Hall in Morpeth and where June will be giving talks on 21 and 27 March.

Karen Lounton at Northumberland County Council praised June Watson's work

June - who is completing a PhD at Northumbria University and is supported by Northern Bridge - spent months wading through 60 large boxes each containing 300 letters and documents.

They detailed the intricate workings of the Tankerville dynasty, stored at Northumberland County Council's Woodhorn archives in Ashington after being donated by the family.

She had to get the permission of Lady Emma's descendants to look through the boxes and what she found painted the picture of Lady Emma's life.

She had exchanged letters with George Washington and other notable citizens of the 18th and 19th Century she could call friends and acquaintances, before her death in 1836 at the age of 84.

Lady Emma collected plants from around the world

"She was a remarkable woman who deserves to be recognised as a significant botanist, artist and collector of exotic plants," June said, adding: "She captured the spirit of women's intellectual engagement with natural history of the period whose important legacies to botany disappeared from the record."

Karen Lounton, interim head of service at Northumberland County Council said June's work discovering and telling Lady Emma's story had been extraordinary.

"[Emma] was a talented woman who did not get the credit she deserved," Karen said, adding: "The work June has done has gone a long way to making sure [Emma] has her moment in the sun and her place in history."

June is giving talks at County Hall in Morpeth about Lady Emma on 21 and 27 March

Lady Emma's collection is one of the largest private collections in the Kew archives, bettered in size only by more official and professional collections like that amassed by William Roxburgh of the plants at Calcutta Botanical Gardens where he was superintendent.

But Lady Emma did not receive any official recognition for her work with women not allowed to join the Royal Society, the body most likely to reward scientific endeavours such as hers.

"It is a beautiful collection to have and is one of our jewels," Ms Parker said of the Tankerville paintings, but she added more needs to be known about the "obscure but very important figure" who put it together.

"She definitely does not get the recognition she deserves."

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published16 September 2021

- Published24 January 2016

- Published23 October 2015