Huntington's disease: Service for patients in Northern Ireland 'overwhelmed'

- Published

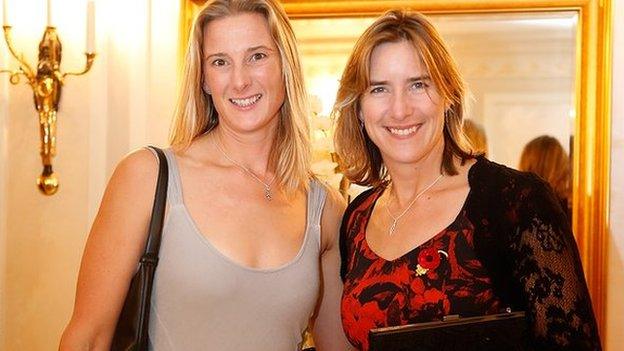

Prof Patrick Morrison said the service for people with the disease is currently overwhelmed and understaffed

A leading expert in Huntington's disease has described the service for patients in Northern Ireland as being seriously overwhelmed.

Patrick Morrison, professor of human genetics at Belfast City Hospital, hit out at the lack of specialist staff.

He accused the government of "failing" patients with Huntington's disease.

The condition is a rare, inherited and highly complex neurodegenerative disorder that affects more than 120 people in Northern Ireland.

Unfilled posts

Huntington's disease is caused by a faulty gene which progressively destroys the central area of the brain, affecting all aspects of the person's life including physical, cognitive and behavioural processes.

"The current service is severely overwhelmed and understaffed," Prof Morrison said.

"For such a tragic condition where the funding of NHS services by the government has not stepped up to the mark, this is failing families with Huntington's disease."

The BBC has learned there are no dedicated specialist nurses currently in place across any of the five health trusts in Northern Ireland to care for patients with this chronic and debilitating condition.

The Belfast Health Trust is the only Northern Ireland trust that has two dedicated Huntington's disease nursing posts. However, due to one nurse being off ill and another changing job, currently neither post is filled at present.

Asking for help

About 120 men and women are affected by Huntington's disease, but the actual figure is believed to be higher as many cases are undiagnosed.

Patients from as far away as County Fermanagh have been contacting the Belfast Health Trust asking for help.

In a statement to the BBC, a spokesperson for the Belfast Health Trust said it "had difficulties recruiting a specialist nurse to work in this team".

"We have actively encouraged existing staff who may be interested in applying for the vacant post," they said.

"The post has been re-advertised. In the meantime we continue to do our best to meet the needs of our service users.

"There is currently a proposal in process to secure additional funding for a regional manager which would further enhance the service."

Anne Boyd says her concentration and mobility have been affected by the disorder

In the meantime, patients have told the BBC they are relying on their families and GPs for help.

One of those patients is Anne Boyd, who lives in west Belfast.

'Especially cruel'

Diagnosed with the condition 11 months ago, Ms Boyd said she is learning to take one day at a time.

"I began noticing a lot of changes," she said. "I was dropping things and falling over.

"There was also a bit of a devil in me. I was nasty, hard to live with. I wasn't a nice person."

Huntington's disease progresses at different rates.

Those who have had it or have witnessed a loved one suffer have described it as being especially cruel, as it affects both the mind and the body.

Depression

According to Ms Boyd, as her memory has been affected she can no longer read.

Her concentration and mobility are also affected and as she is confined to her home a lot of the time, she also suffers from depression.

"I get up every day not really knowing what it may bring," she said.

"It is really hard and not just for me, but for my family. They need help too."

According to Prof Morrison, Huntington's disease is one of the worst disorders a person can get.

"It starts with movement problems and progresses to the centre of the brain," he said.

"There are memory issues, temper outbursts and a person becomes irritable. There are striking neurological and psychological features too."

Testing dilemma

A person with Huntington's disease has a 50% chance of passing it on to their children.

According to Prof Morrison, it can have a massive impact on families.

Ms Boyd's brother has also been diagnosed. Another sibling has decided not to be tested.

Her children are also faced with the dilemma of whether or not to be tested. One son has already started the process of counselling.

"It's their choice," Ms Boyd said. "They will all decide in their own time what's best for them."

Diagnosed in January, Ms Boyd said the news came as a relief.

Isolation

"The day the doctor told me my results I said 'thank God - at least I know what's wrong with me'," she said.

"The doctor remarked on my reaction - but they said that was the mummy and the granny in me.

"Now that I knew, I could get on with my life and organise getting things done."

Those who have lived with the disorder for decades say it can cause many years of fear, shame and isolation not just on one person, but over successive generations.

Prof Morrison said the service based at the Belfast Health Trust is busy.

"Not only are we receiving more requests for testing but clearly there are more people out there requiring help," he said.

'Short-changed'

"Two nursing posts in Belfast is clearly not enough. Every trust needs dedicated nursing teams.

"This is a rare condition and specialist nursing is required. It puts a strain on everyone, including staff.

"Therefore it needs planning on the part of the government when it comes to funding care."

In Scotland and England there is at least one specialist nurse for every 50 patients with Huntington's.

Prof Morrison said patients in Northern Ireland are being short-changed.

"There are also specialist nursing units and nursing homes in Scotland," he said.

"In Northern Ireland patients aren't always receiving the appropriate care in the appropriate place."

'Better understanding'

The issue is gathering momentum among health specialists in the community and the Huntington's Disease Association of Northern Ireland has appointed a manager - Sorcha McGuinness.

The human rights campaigner has previously led investigations into the rights of homeless people.

"We need to lobby the executive more about more funding for patients and their families," Ms McGuinness said.

"There also needs to be a better understanding and awareness among the public. I aim to do that."

The Northern Ireland Rare Disease Partnership (NIRDP) is holding a series of open public meetings, external next week allowing people to help shape the future of their healthcare.

Up to 100,000 people whether they are patients, carers or family members are impacted by rare disease in Northern Ireland.

Conditions include: motor neurone disease (MND), muscular dystrophy, spina bifida, Huntington's disease, vasculitis, spinal muscular atrophy, lupus as well as rare forms of cancer.

Related topics

- Attribution

- Published15 July 2014

- Published5 October 2012

- Published12 April 2012