Orange Order on the equator: Keeping the faith in Ghana

- Published

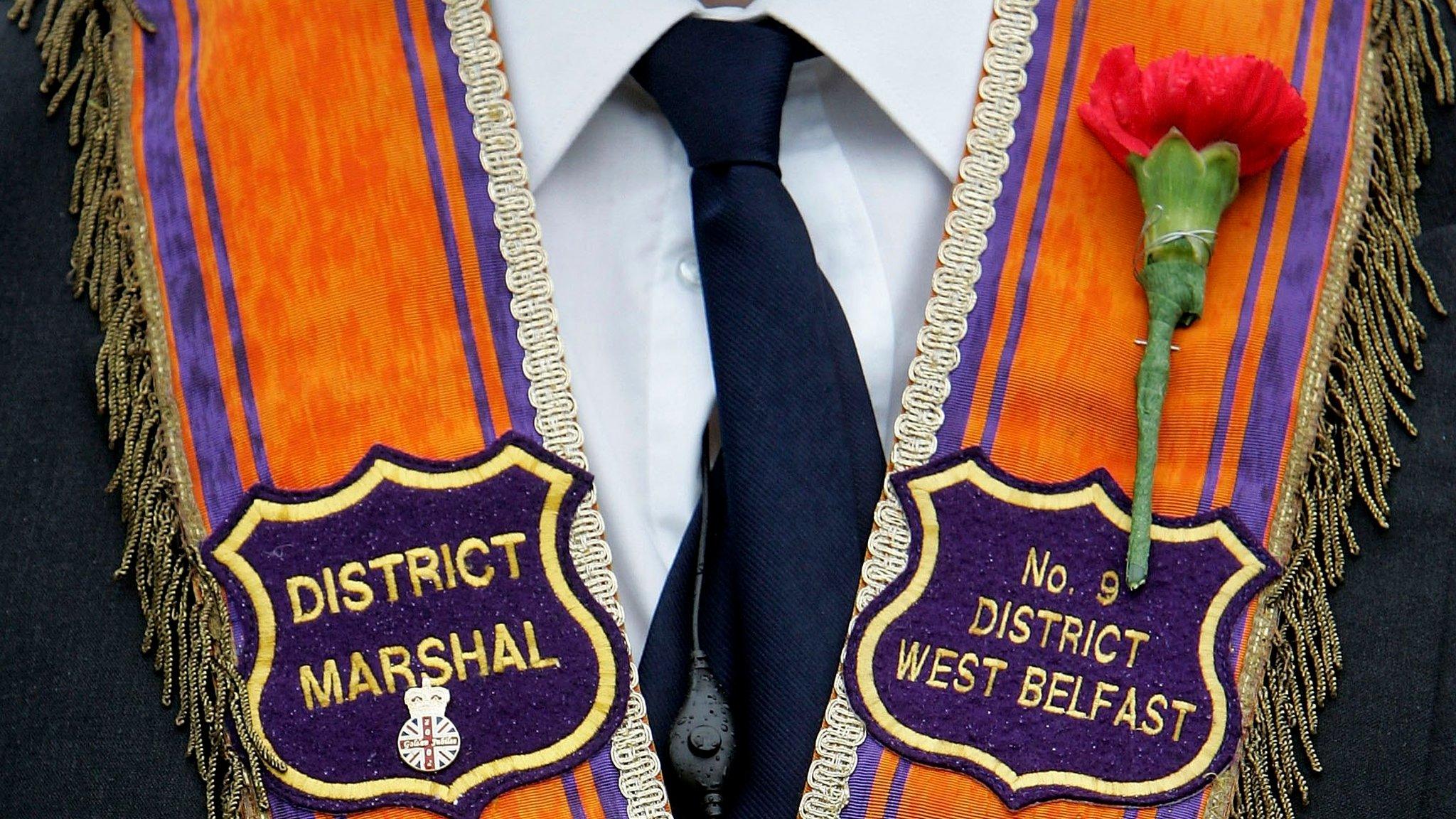

Orange Order members in Ghana say their Orangeism is a way of practicing their Protestant faith

Torchlight shines on a wall with paintings of battle scenes from the late 17th Century.

It's just after 17:00 local time, so there's no power yet - the electricity comes on at 18:00.

The battery-powered beam reveals a familiar picture of a king on a white horse.

He is the Dutch-born British monarch King William III, a man whose image is on many gable walls in Northern Ireland.

But this is one-and-a-half continents away from Belfast.

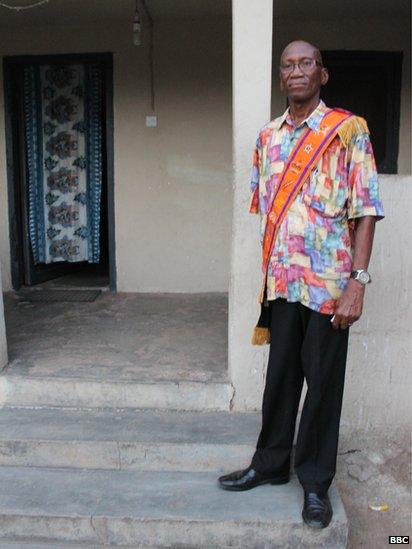

I'm on the outskirts of Accra, in the home of Dennis Tette Tay, the acting grand master of the Orange Order in Ghana.

Dennis's living room is full of photos, paintings and certificates relating to the order.

He tells me Orangeism is "in his soul".

Outposts

One photo pictures Dennis in a sash, along with Emmanuel Aboki Essien, who was the first African to be president of the Imperial Orange Council, the leader of worldwide Orangeism.

"Maybe I will be the second," says Dennis with a gentle laugh.

Ghanaian Orangeman Dennis Tette Tay says Orangeism "is in his soul"

The Orange Order was founded 220 years ago, named after the king who defeated a Catholic army at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690.

On 31 August BBC Radio 4 will broadcast Orangemen On The Equator.

It is perhaps unsurprising that the order has outposts in countries like Australia and Canada where ex-pats from Northern Ireland have emigrated.

But that is not how the order took root in the West African countries Ghana and Togo.

The first Orange lodge in what is now Ghana was founded in 1918.

Then it was a British colony, the Gold Coast.

Suspicion

A postal worker read about the order in a newspaper and wrote to the organisation in England asking to join.

The Grand Orange Lodge of Ghana, like the eight other national grand lodges, operates independently while maintaining links with the global Orange organisation.

The order says there are several hundred members in Ghana but numbers have declined.

One of the reasons why it was eager to tell us its story was to correct myth and rumour.

Parading in Ghana has never been controversial, but there has not been a march for some years now

In Ghana, there is often suspicion around lodge-based organisations.

Popular films show members engaged in occult activities.

Orangemen and women find this hurtful and emphasise that their Orangeism is simply a way to practise their Protestant faith.

Deputy grand master Togbi Subo II says: "The order enlightens one's spiritual living.

Watershed

"When you go deep into the learning and doctrines of the order, you know you are closer to Christ."

Northern Ireland is a much more secular society.

There the organisation is considering its future direction as the Troubles recedes further into the past.

A Ghanaian flag is one of nine flying outside the Museum of Orange Heritage in Belfast.

It is one of two museums recently opened by the order, in a project that they regard as something of a watershed.

"We have to stay relevant," says Drew Nelson, grand secretary of the Grand Lodge of Ireland.

Drew Nelson says the Orange needs to think carefully about its direction if it is to remain relevant

"If we cut ourselves off from society and retreat behind the walls, we will eventually fade from the pages of history."

So the museums tell the Orange story from the order's point of view, and they are hoping to attract Catholics to visit.

Unity

In Northern Ireland, the Protestant brotherhood has been viewed by many Irish nationalists as anti-Catholic.

Parading disputes, such as those at Drumcree in the 1990s and north Belfast more recently, have generated negative headlines.

But the order says the true essence of its organisation is faith and fraternity, and that Orangeism's continued existence abroad shows this.

Making this programme took us from the humid, heaving city of Accra, to the sea-ravaged but resilient town of Keta, where Ghanaian Orangeism was born.

Producer Conor Garrett and I got a sense of the unity of Ghana's numerous ethnic groups on the country's Independence Day.

We also had the rare experience of observing a Ghanaian Orange lodge meeting in a seaside church with an unfinished Orange hall outside.

The journey also featured the tri-annual conference of international Orange Order members, in Liverpool, and the flagship Twelfth of July parade in Bessbrook, County Armagh.

A sense of the unity of Ghana's numerous ethnic groups can be felt on the country's Independence Day

The order in Ulster points out that the vast majority of Orange marches are like that one - peaceful and non-contentious.

Misunderstood

Post-colonial Ghana and post-conflict Northern Ireland are very different cultural contexts.

In Ghana, parading has never been controversial.

But there hasn't been an Orange march for some years now.

However, one of the favourite hymns of the Ghanaian Orange Order members is Marching To Zion.

Like their counterparts in Northern Ireland, they often feel maligned and misunderstood, though not for the same reasons.

They may be numbered in the hundreds rather than the tens of thousands, but the Orangemen on the equator have a deep commitment to the fraternity founded in Ireland in 1795.

As they have faith for new members to carry them into a second century, they also hope to see a time in the Order's heartland where belief will be unifying rather than divisive.

Togbi Subo II says: "It is our prayer that one day misunderstanding will be over in Ireland."

Orangemen On The Equator will be broadcast on BBC Radio 4 at 20:00 BST on Monday 31 August, and will be available on the BBC iPlayer.

- Published11 July 2012