Battle of the Somme: The story of the 'only speaking artefact'

- Published

Drummer Jack Downs of the 36th Ulster Division was a member of the First Derry Presbyterian Church

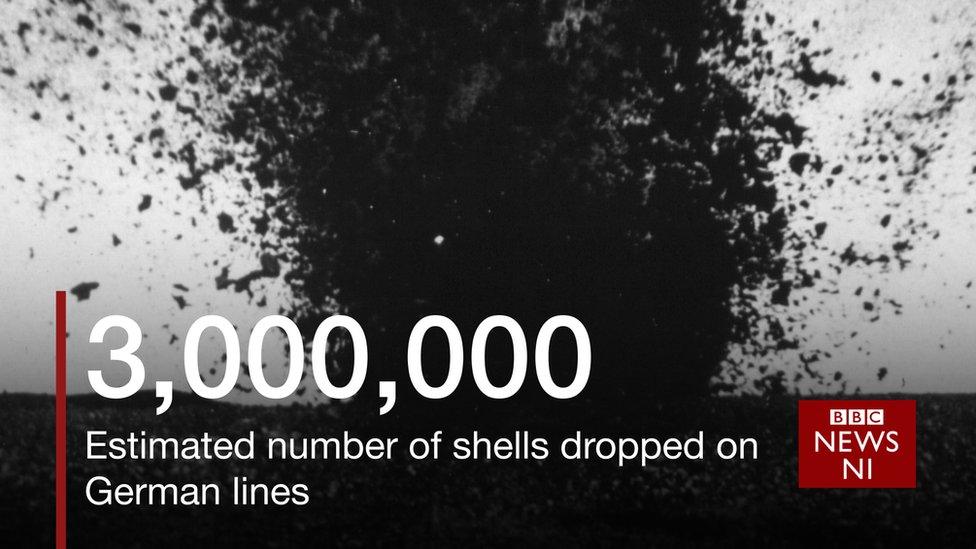

On the morning of 1 July 1916, the guns fell silent, marking the end of a seven-day Allied bombardment of the German trenches at the Somme.

As the barrage lifted, bugles and whistles signalled as 100,000 men went over the top.

One of those was sounded by Drummer Jack Downs of the 36th Ulster Division.

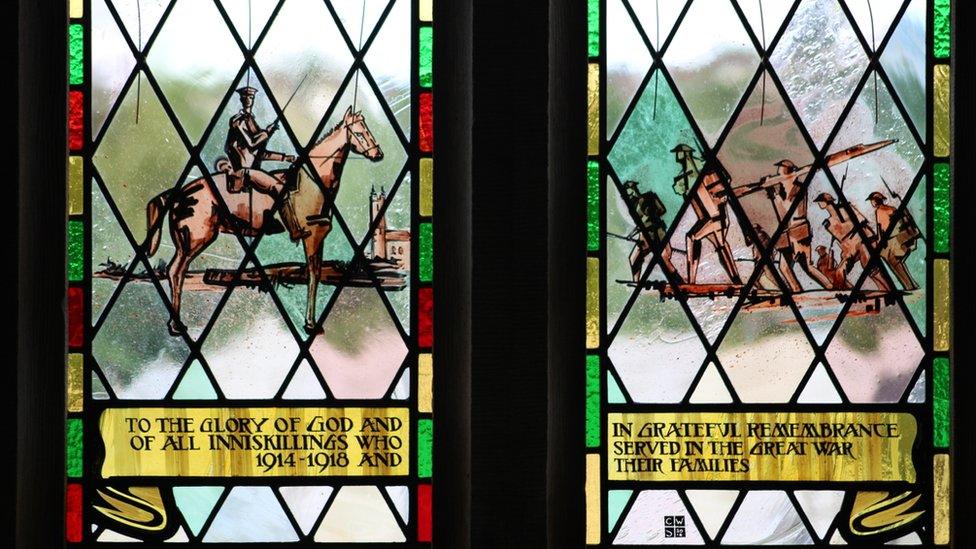

A member of First Derry Presbyterian Church, he joined the 10th Battalion Inniskillings, Derry Volunteers, at the outbreak of the World War One.

Drummer Jack Downs sounds the Advance, playing the same bugle used 100 years ago

In response to the bugle call the men left the trenches and rushed to the German frontline.

In the first two days of the battle, the 36th Ulster Division suffered almost 5,000 casualties and about 2,000 of those men were killed.

Downs' battalion had over 130 fatalities, but he would survive to fight another day.

When going on leave in November 1916, he was presented with his bugle by Colonel Macrory, who told him to have the following inscription engraved on it:

"On this bugle was sounded the famous charge of the Ulster Division on 1 July, 1916, at Thiepval, by Bugler J. Downs, 15486, 10th Inniskillings, also the retire for the raiding party who captured the machine-gun at Kemmel Hill on the night of the 30th September, 1916."

The bugle was one of those which sounded as 100,000 men went over the top

Drummer Downs' war continued, and he fought at Messines in June 1917, but he would not return home.

He was killed during the retreat from Cambrai in March 1918.

His iconic bugle is now part of a collection at the Inniskillings Museum.

It again sounded the advance at 07:30 on Friday, exactly 100 years after its call sent the men into battle, as part of a day of Somme centenary commemorations at Enniskillen Castle.

It was played by Portora Royal Grammar School pupil Stephen Humphries, who said it was "an honour".

"It was very different to a normal bugle - it's dented and it was very difficult to get the hang of - but it's very emotional as well as [Downs] was killed in action," he said.

"It's crazy, I'm only 17 and I don't know how schoolboys could just go off to war.

"It just doesn't seem normal at all to me."

Neil Armstrong, the curator of the Inniskillings Regimental Museum, said hearing the sound of the bugle was "very emotive".

"I suppose it's the one artefact within our collection that can speak," he said.

"Certainly medals and photographs and letters are very poignant but this is the exact sound that our relatives would have heard 100 years ago, and that's the most important thing and I think that's how we managed to link with that occasion."

Mr Armstrong, whose great grandfather served with the 11th Battallion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers and was killed on the first day of the Somme, said he had mixed emotions during the commemoration.

"Right now as we have gone beyond zero hour, it must have been horrendous conditions for the Inniskillings," he said.

"We can't even contemplate what they were doing and how many, even by this stage, would already have made the ultimate sacrifice for the division."

- Published1 July 2016

- Published1 July 2016

- Published29 June 2016