Northern Ireland Assembly divided by Irish language

- Published

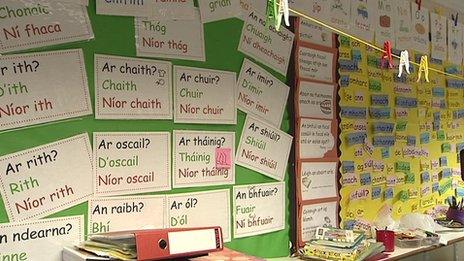

Irish is seen as important to the wider nationalist community as a symbol of identity

There are few places in the world where the issue of manhole covers would cause a political row.

However, when a unionist councillor in Ballymena complained that new covers installed in the town included the word "uisce", no-one was particularly surprised.

This is because "uisce" is the Irish word for water - two of the new covers installed as part of an improvement scheme were found to be bilingual.

The difficulty was 'resolved' by the Irish word being scraped off, but it was an illustration of how polarised attitudes to the Irish language are in Northern Ireland.

Despite only a minority of the population speaking Irish as a vernacular, the language is seen as important to the wider nationalist community, and a small number of unionists, as a symbol of identity.

It is, in turn, vigorously resisted by many as a symbol of resistance to that identity.

'Curry my yoghurt'

The result is almost total polarisation of the issue among politicians, nowhere more so than in the Northern Ireland Assembly, where clashes on the language issue have made headlines.

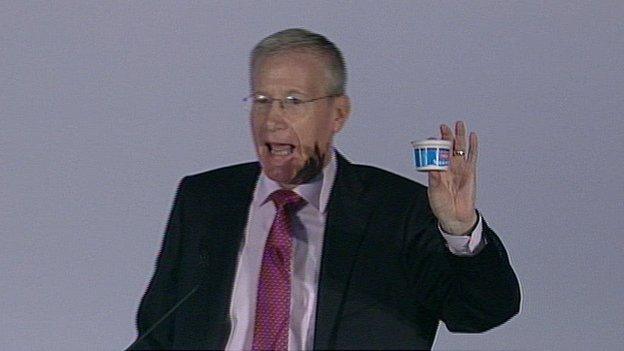

In 2014, the DUP's Gregory Campbell was barred from addressing the assembly for a day for parodying the language and after failing to apologise.

He began a speech with: "Curry my yoghurt can coca coalyer".

The Irish sentence "go raibh maith agat, Ceann Comhairle" translates as "thank you, speaker" and is used by Sinn Féin, and to a lesser extent, the SDLP, members to address the Stormont Speaker as "ceann comhairle" - in a similar fashion to the way the speaker is addressed in the Dáil (Irish parliament).

Mr Campbell said: "My tolerance gets stretched beyond any credibility when I hear Irish ad nauseam on hundreds of occasions for no purpose other than a political one".

The speaker said Mr Campbell's conduct fell "well short of standards expected from MLAs".

The then deputy first minister, Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness said the incident "bordered on racism".

Gregory Campbell, when invited to speak, said "curry my yoghurt can coca coalyer"

The clashes have continued. DUP Agriculture Minister Michelle McIlveen took the decision in September 2016 to rename a fisheries protection vessel from the Irish name given to it by a previous Sinn Féin minister, Michelle Gildernew.

Thus 'Banríon Uladh' became 'Queen of Ulster', a direct translation.

Same ship but a new name - this time, in English as opposed to Irish

Ms McIlveen said the move was part of a change to a "single language policy" and an attempt to give her department "a fresh identity".

Irish language group Pobal said it "deplored" the change, describing it as "a sad and petty action, which brings no benefit or value to a society struggling to move away from inequality and discrimination".

DUP Communities Minister Paul Givan's decision to withdraw funding for an Irish language bursary scheme two days before Christmas, which was subsequently revoked, is seen by Irish speakers as the latest battle in a cultural war.

Dr Niall Comer, president of Comhaltas Uladh, the Ulster Irish language organisation, called the move a "blatant act of discrimination".

Mr Givan said his original decision was not political, but Martin McGuinness cited the £50,000 cut as one of the reasons for his resignation as deputy first minister.

The subject of Irish medium education (IME) is also hotly debated in the chamber, where arguments on whether or not to officially recognise an Irish medium school will invariably split the parties along traditional lines.

IME is legislated for in the 1998 Education Order, however, limiting the scope for disagreement.

In recent years, assembly debates have focused on demands for an Irish Language Act - a legislative framework for the language.

The Irish language umbrella group, Pobal, has been focusing on the question of an Irish Language Act since 2003 and its chief executive, Janet Muller, said: "The Irish Language Act was promised in the St Andrews' Agreement in 2006.

"More than ten years on, it is more than time to move this issue forward.

"The political parties and the Irish and British governments now have the opportunity to resolve this outstanding issue.

"We welcome Sinn Féin's emphasis on the act, and call on them to state clearly that there will be no return to Stormont without a detailed guarantee and timescale on Irish language legislation."

Other Irish language groups have also lobbied for legislation which has the political support of both the SDLP and Sinn Féin.

The Alliance Party supports the creation of a comprehensive languages act covering "indigenous languages and other spoken languages used within Northern Ireland, as well as various sign languages.

But both main unionist parties oppose the proposed legislation.

Irish language activists point out that the Gaelic Language Act protects Scottish Gaelic in Scotland, despite the fact that, according census figures, there are fewer speakers of Gaelic in Scotland than Irish in Northern Ireland.

Graffiti in Belfast calling for an Irish language act, a proposal that divides the assembly along traditional community lines

However, their opponents make the point that the vast majority of those speakers in Scotland are native speakers, brought up speaking the language, whereas the majority of Irish language speakers in Northern Ireland are not.

Sinn Féin attempted to introduce the Irish language bill in the assembly in 2015. The DUP criticised the effort as "futile" and it did not gain the necessary support to become law.

The SDLP had a private members bill on the issue before the assembly before it collapsed, the second such attempt it had made on the issue.

Political debate rarely involves the actual content of a possible Irish language act, focusing more on the general principle of whether there should be legislation or not.

Many Irish language activists call for legislation that would guarantee Irish was given the same official status as English.

That would lead to measures like:

The option for Irish to be used in court

Irish being used in assembly debates

The widespread use of Irish by all state bodies including the police

The appointment of an Irish Language commissioner to ensure the language is facilitated

The right to be educated through the Irish language

Bilingual signage on public buildings and road signage.

The DUP MP Gregory Campbell told his party conference in 2014 that the party would never agree to an Irish language act.

His party leader Arlene Foster re-iterated that stance in February this year, telling a party event: "If you feed a crocodile it will keep coming back for more."

She later said she regretted that remark and struck a more conciliatory tone when she visited pupils studying the Irish language at a Catholic school in Newry, even going as far as saying thank you in Irish.

However, with political flux at Stormont, many Irish language speakers saw a chance to put demands for an act at the centre of those negotiations - calling on Sinn Féin and the SDLP to make an Irish language act a "red-line issue".

Thousands of Irish language activists attended a march and rally in Belfast earlier this year calling for language legislation in what was certainly the largest demonstration of its kind ever held in Northern Ireland.

Irish language groups have continued to press for "stand-alone rights based" legislation throughout the latest round of talks as Stormont aimed at re-establishing Northern Ireland's power sharing executive.

Privately, though, many fear that comprehensive language legislation, as exists in Wales, is highly unlikely to ever come about, given steadfast unionist opposition.

The language remains one of the key sticking points preventing the parties coming to an agreement although reports suggest that the DUP may be willing to accept that some sort of legal provision for Irish could be included as part of a wider 'Culture Act' which would include Ulster-Scots, a form of Scots taken to Northern Ireland during the Plantation of Ulster by Scottish settlers.

Irish language groups say that that would not be acceptable as there is no demand from Ulster-Scots speakers for legislation and because Ulster-Scots is in a very different linguistic situation from the Irish language.

Language Facts

According to the 2011 Census 8% of Northern Ireland's population claim some knowledge of Ulster-Scots, external - just over 140,000 people.

Over 179,000 claim some knowledge of Irish according to the 2011 census, almost 11% of the population, however only 4,045 said that Irish was their main language.

Place-names in Northern Ireland come from a variety of sources, however the vast majority derive from Irish.

There were over 6,000 children being educated through Irish in Northern Ireland in 2016-17 according to Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta, the body which promotes Irish medium education, there are no schools teaching through Ulster-Scots.

- Published20 May 2017

- Published6 February 2017

- Published17 December 2014

- Published29 September 2016

- Published12 January 2017

- Published4 November 2014

- Published26 January 2015

- Published16 January 2014