Article 50: What to look out for in Northern Ireland

- Published

- comments

Theresa May has said her goal is for the UK to build a "deep and special partnership" after Brexit

The Prime Minister has signed the letter notifying the European Union that the UK is leaving and will trigger Article 50.

Theresa May has said her goal was for the UK to build a "deep and special partnership" after Brexit.

Talks on the terms of exit and future relations are expected to take two years.

There has been a lot of speculation and debate about the prospect of a so-called hard border since last June's EU Referendum vote.

But what else should Northern lreland look out for during this process? BBC News NI specialist correspondents take a look at the key issues that will impact us.

Business and economy - Julian O'Neill

The manufacturing industry in Northern Ireland has been broadening its export horizons

Northern Ireland's biggest export market remains its nearest neighbour.

Just under one third of its total manufactured goods - £2.4bn - were sold across its land border in 2016. But increasingly the region has been broadening its horizons.

Many companies will not want cross-border trade to be damaged by Brexit and whatever border arrangements follow.

Selling beyond Ireland and outside the European Union is becoming more of a priority. To this end, Invest NI, the jobs promotion agency, is opening up to 10 new offices worldwide.

Chile and Singapore are among its latest outposts. After the Irish Republic, Northern Ireland's largest customer is the United States.

Around £1.6bn worth of goods were sent stateside in 2016, up 41% off the back of a weaker pound.

It would be wrong, however, to understate the importance of EU markets.

Of Northern Ireland's £7.7bn export total, the majority of sales (£4.2bn) were to the EU.

But growth in non-EU export markets has been accelerating at a quicker rate in recent years.

The business community probably desires the best of both worlds - a negotiated free trade arrangement involving the EU, with the UK cutting deals with other big economies like the US and China.

But that could be a huge ask - especially within a two-year time frame.

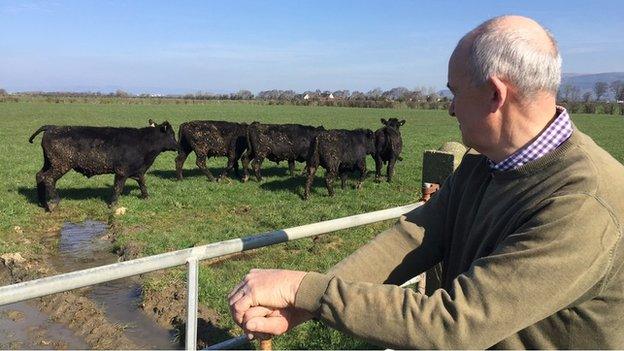

Agriculture and environment - Conor Macauley

Northern Ireland currently gets 10% of the UK's European subsidy payments

Farmers in Northern Ireland had hoped to maintain their farm subsidies post-Brexit. The EU contributes about £250m a year to farmers.

But all the indications from government are that the annual cheque is a thing of the past.

Instead it looks increasingly like support will be much more targeted through things like agri-environment schemes - in which farmers are rewarded for environmental services such as flood prevention work and biodiversity schemes.

And there's a suggestion that there'll be a greater reliance on things like insurance and futures markets to help manage volatility in prices paid for what they produce.

In November, the Assembly was told farmers and the agri-food industry need a post-Brexit strategy to stop them "falling off the edge of a cliff" once the UK leaves the EU.

The call was made during a debate on the future funding of farming.

The Assembly heard claims that funding agriculture was not a priority for the UK government.

Northern Ireland currently gets 10% of the UK's European subsidy payments.

Speakers, including the SDLP's Patsy McGlone, said it would not do as well under a domestic agricultural policy.

If the Barnett funding formula - used to calculate Northern Ireland's share of UK budgets - was applied the equivalent share would be 3%, he said.

But the DUP's Edwin Poots said farmers had voted "overwhelmingly" for Brexit, adding that it offered them opportunities.

These included displacing agricultural produce currently imported to the UK.

He said farmers did not want "handouts", but a fair return for their work.

Education - Robbie Meredith

One fifth of staff at Queen's University are from the EU but not the UK

Queen's University and Ulster University have warned that leaving the EU risks their ability to attract international staff, students and EU research funding.

Both universities have carried out their own internal studies analysing the possible implications of Brexit.

The number of EU students applying to Queen's dropped by 6% this year, while one-fifth of its staff are from the EU but not the UK.

Meanwhile, Ulster has warned that Brexit puts 20m euros (£17.5m) of EU funding and tuition fees in doubt.

Both have asked for reassurances about the immigration status of international staff and students, and continued access to European research funds.

Concerns have also been expressed that Northern Ireland students wanting to study in the Republic of Ireland would have to pay much higher tuition fees in future if they are classed as non-EU students.

While uncertainty is most acute in higher education, a number of schools here also participate in the EU funded Erasmus+ programme which sees them partner with, and send pupils to, schools in other European countries.

Like the universities, they too will hope the forthcoming negotiations provide guarantees that there will still be some access to EU money and projects in future.

Health and social care - Catherine Smyth

An acute shortage of nurses has prompted four international recruitment drives in the past two years

One of the areas of concern will be the continued ability of EU nationals to work in Northern Ireland's health and social care system.

At the moment there are 1,000 nursing vacancies: The acute shortage of nurses led to four separate international recruitment drives in the past two years.

In 2016 around 50 job offers were made to nurses from Italy and Romania, although the bulk of the jobs - around 490 - were offered to nurses from further afield in the Philippines.

The health unions are urging the government to clarify its intentions - there is concern that some foreign nationals may feel it necessary and safer to return home.

Cross-border services are another issue where the implications of Brexit are yet to unfold.

After years of negotiation, a new cancer centre in the north-west has finally opened and is offering treatments to people on both sides of the border.

For some patients this can mean travelling a distance of 10 miles in order to cross the border. The cancer centre, radiotherapy services and paediatric cardiac surgery are all cross-border services that politicians and the public have campaigned to get for decades - services they will not want to give up easily.

Some of these services are provided by cross border workers. They may live in one area such as Donegal but work in Northern Ireland.

Those people can get a medical card in Northern Ireland and be seen as "free workers".

One of the most contentious pieces of EU law affecting the health service in NI is the working time directive: If the Westminster government decides to repeal or amend it, this could have implications for local employment contracts, as well as pay and conditions.

EU law has also provided a harmonised approach to medicines regulation.

The European Medicines Agency is currently based in London, but Health Minister Jeremy Hunt said in January this was "likely" to move outside the UK.

Could a beneficiary be the Republic of Ireland? The Republic's health minister is currently compiling what he argues is a heavyweight case for Dublin to host the medicines regulator.

Finally, Queen's University is among those that have built up reputations as centres of excellence for cancer research.

Academics have called for the Brexit negotiations to consider how these centres can continue to play a role in cross-continental projects, while attracting top international staff and funding.

Politics - Mark Devenport

With no power-sharing executive in place, Stormont politicians have little, if any, influence over Brexit negotiations

The triggering of Article 50 looks likely to further exacerbate the divide between the Stormont parties, who are already unable to form a power-sharing executive.

The DUP and Sinn Fein campaigned on different sides before last June's EU referendum.

But their leaders were able to patch up their differences and sign a joint letter to Theresa May last August.

That letter set out shared concerns about the border, trading costs, the energy market, EU funding and treatment of the agri-food sector.

Since then, though, relations between Stormont's two main parties have nose dived.

Now the DUP continues to emphasise the opportunities presented by Brexit, whilst Sinn Fein, the SDLP and Alliance have all backed Northern Ireland retaining some kind of special status within the EU.

With no power-sharing executive in place, Stormont politicians currently have little, if any, influence over the Brexit negotiations.

However, London and Dublin are both committed to maintaining as open a border as possible, whilst the EU's Chief Brexit Negotiator Michel Barnier says the EU will not stand for anything that weakens dialogue and peace in Northern Ireland.

- Published28 March 2017

- Published29 March 2017

- Published24 June 2016

- Published20 March 2017

- Published29 March 2017

- Published30 December 2020

- Published24 June 2016