Sign language act: Should it be a 'bigger priority' than Irish language?

- Published

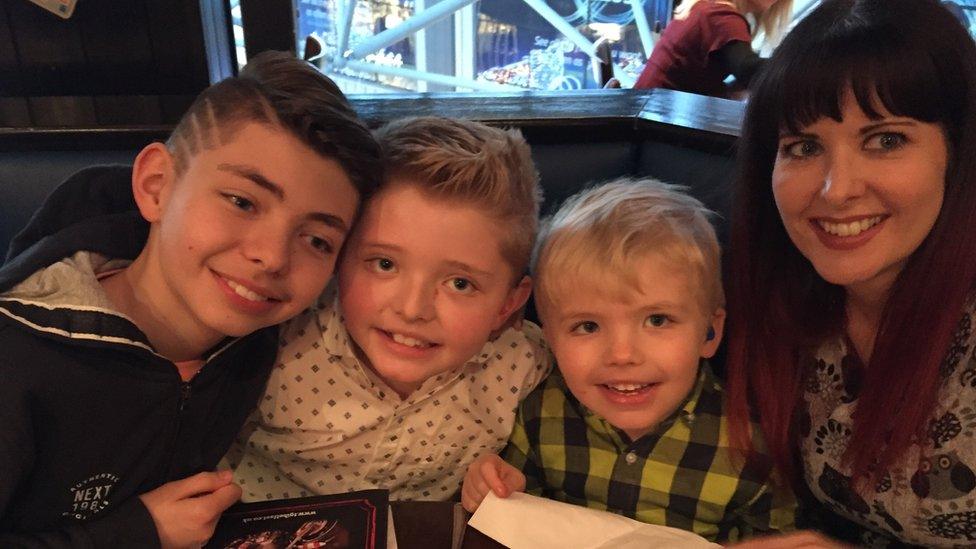

Wendy Newbronner said she had never met a deaf person before she had her children, who all have hearing difficulties

Every morning, County Antrim woman Wendy Newbronner's first task is waking up her three children.

Unlike most parents though, she cannot shout into their rooms and tell them to get up. All her sons are deaf.

Mrs Newbronner had to pay to learn sign language after her first child was born, and now supports calls for a sign language act in Northern Ireland.

Scotland is the only part of the UK with an act, but legislation was passed in the Republic of Ireland, external last year.

The problem is, without a functioning Stormont assembly, legislation for sign language in Northern Ireland cannot be introduced.

'Paying a fortune'

Northern Ireland's power-sharing executive between the DUP and Sinn Féin collapsed almost 18 months ago, and the parties remain locked in a stalemate over, among other issues, demands by Sinn Féin for an Irish language act.

"An Irish language act is all well and good, but for me, sign language is a bigger priority. Parents (of deaf children) are paying a fortune to learn to communicate with their child on a day-to-day basis," said Mrs Newbronner.

"If kids were taught sign language in school, there wouldn't be that barrier between the deaf and hearing community.

Wendy's three sons go to a school where they are educated through sign language, but she wants to see all schools in Northern Ireland teaching it

"People would feel confident when in a situation with a deaf person, and imagine how that would feel for my boys, if someone they didn't know could sign with them?"

British and Irish Sign Languages were given official status as minority languages in Northern Ireland in 2004, but the British Deaf Association (BDA) has said that does not go far enough.

At present, sign language is not required to be on the school curriculum and there are only 32 sign language interpreters working across Northern Ireland.

The BDA has been campaigning for a sign language act for decades, and is disappointed by the lack of progress.

Majella McAteer is the organisation's community development manager. She is deaf, and when I met her at her office, she spoke to me through her interpreter, Rosie.

'Never give up'

"The deaf community are very frustrated," she said.

"We're told funding is available for other languages, which are classed as cultural issues and that's why the money is available, but somehow money is never available to us.

"A lot hinges on Stormont or we'll have to look at alternative ways to get it through - but we'll never give up."

The British Deaf Association's Majella McAteer at work, talking to someone on the phone with the help of her sign language interpreter

One of the biggest components of an act would be a requirement for Stormont to provide free sign language classes for parents, siblings and grandparents of deaf children.

"90% of deaf kids are born to hearing parents and of course, there is a need for those parents to learn sign language," said Majella McAteer.

"An act means funding for this would become compulsory, which means those parents would have the choice of learning sign language before the child is five. They would be able to learn it by watching their parents sign, and that in turn would increase their language access.

"A lot of parents have to self-fund to go to a college to learn sign language to communicate with their child - that shouldn't have to happen.

'Not an excuse'

"That's why early years intervention is so important, when they leave school at age of 18 they can go on to access more education or employment - it's all part of the journey."

In 2015, Sinn Féin MLA Caral Ní Chuilín was Stormont's culture minister and ordered a public consultation into a draft sign language framework.

Since then, however, devolution in Northern Ireland has collapsed and so too, has the chance for sign language legislation to be passed through the assembly.

But Caral Ní Chuilín told BBC News NI that the political stalemate should not be a barrier for her former department when it comes to making progress.

Caral Ní Chuilín said she believed her former department could do more to help the deaf community in Northern Ireland

"I don't believe the department needs legislation to go ahead and provide free sign language classes or extra support for the deaf community," she said.

"The department is hiding behind the fact that there is no minister, it shouldn't be an excuse."

Ms Ní Chuilín also rejected criticism of Sinn Féin that the party is wrongly focusing on an Irish language act, when some may feel a sign language act should be a bigger priority.

'Second nature'

"Language groups don't want to compare rights, they all say they want the government back up and running on a sustainable basis - and that means providing rights for all minority groups," she said.

A spokesperson from the Department for Communities said it had taken the process as far as it could, and would bring the issue to the attention of any future minister.

She added that the department is working on a range of actions to benefit the deaf community and increase sign language awareness.

Wendy Newbronner says she fears for her children growing up because there is not enough support given to the deaf community in Northern Ireland

But for parents like Wendy Newbronner, every day that goes by without a sign language act leaves them concerned that deaf children are losing out.

"Not having an act causes a lot of gaps in the community," she said.

"It upsets me to think my child's going out into the world when they get older and won't have access to things in the same way I do, things we take for granted.

"If a sign language act was in place, people would learn it and it would become second nature."

- Published24 October 2017

- Published1 June 2017

- Published21 February 2017