Spanish flu: How the 1918 pandemic hit Ulster and beyond

- Published

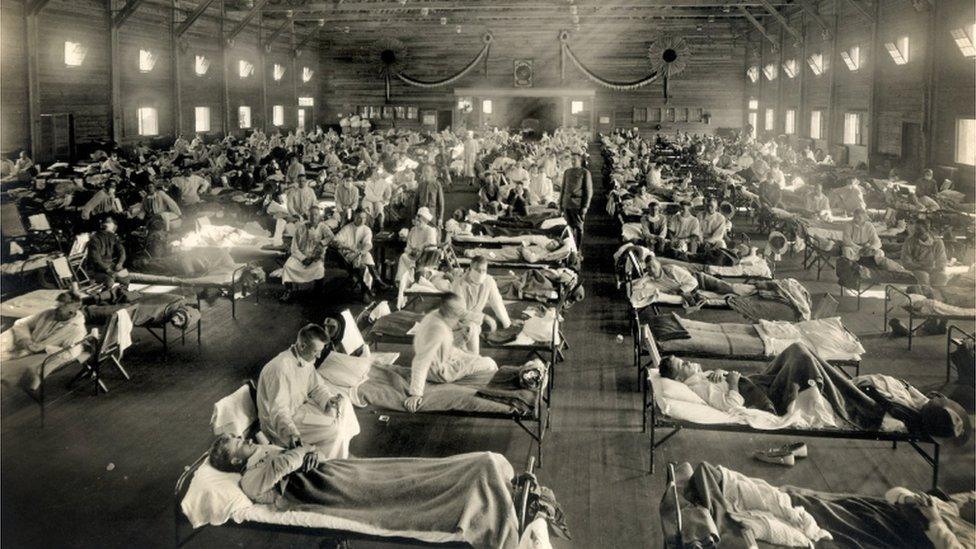

Patients infected with influenza at an emergency hospital ward at an American Army camp in Kansas

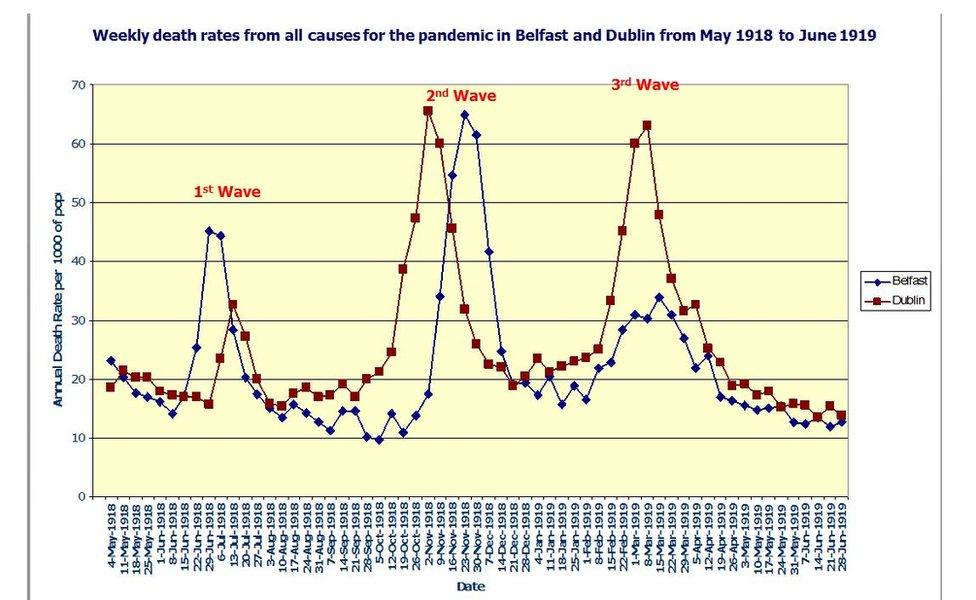

One hundred years ago this weekend, a fortnight after Armistice celebrations brought people to the streets across Great Britain and Ireland, a killer that claimed more lives globally than the four-year conflict reached its peak in Belfast.

In the week ending 23 November 1918, the death rate in the city had tripled from the yearly average for all causes.

Although the recorded reasons varied, historian Dr Patricia Marsh said that the vast majority of deaths were undoubtedly related to a much-feared global pandemic - the Spanish flu.

According to Dr Marsh, it is no coincidence that the death toll soared in the two weeks that followed Armistice Day.

The virus was, by this stage, in its "second wave" in Ulster.

Dr Patricia Marsh's diagram shows how Belfast's death rate soared in the two weeks that followed Armistice Day

"The Spanish flu had returned in October in a much more virulent wave than the previous one, and so the public were advised to avoid cinemas and other confined spaces," said Dr Marsh.

"The authorities were doing their best to try and contain it, but you can't expect people not to come together to celebrate the end of a war.

"You can see from the photos that there were thousands of people on the streets on 11 November. We know now that this is how viruses spread, but back then, people weren't as knowledgeable about the causes of illness."

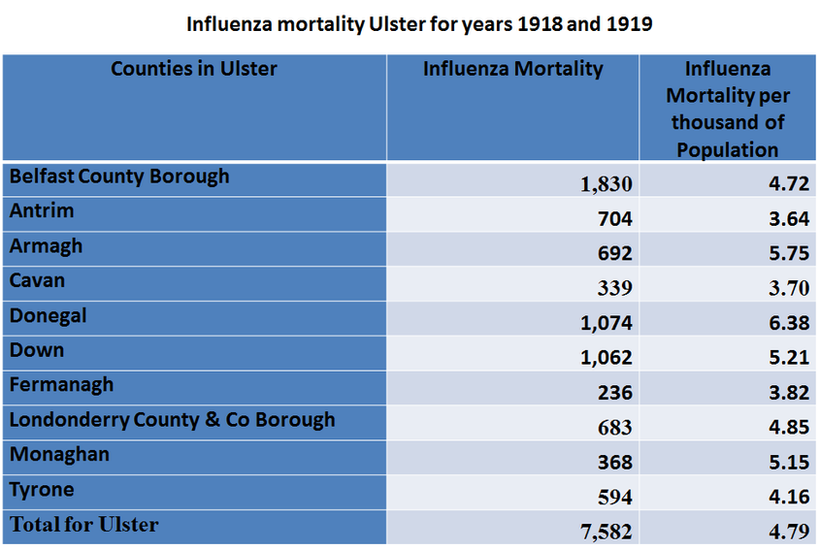

Across the whole island of Ireland, there were more than 23,000 recorded deaths as a result of the virus - approximately 7,500 of those were in Ulster.

However, due to a lack of diagnosis and documentation, it is thought that up to 800,000 people in Ireland could have been infected, according to Dr Ida Milne, of Maynooth University.

Doctors with a 1918 flu patient at a US naval hospital

The pandemic is estimated to have killed up to 100 million people worldwide, reaching countries across the globe, as well as remote pacific islands and even the Arctic.

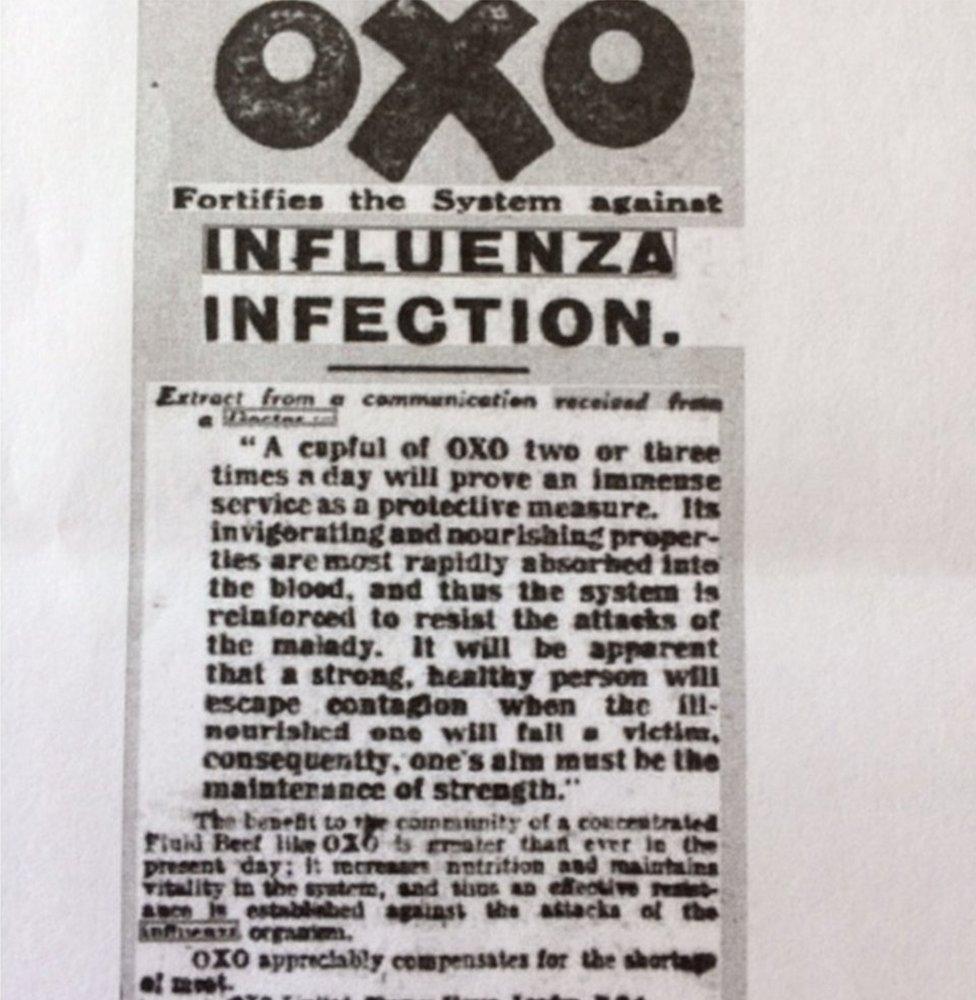

An advertisement hailed Oxo as a preventative of influenza

The movement of troops and goods in a post-war world allowed the respiratory illness to be transported trans-nationally.

In the shadow of World War One, many people were left malnourished and with weak immune systems, making them more susceptible to illness.

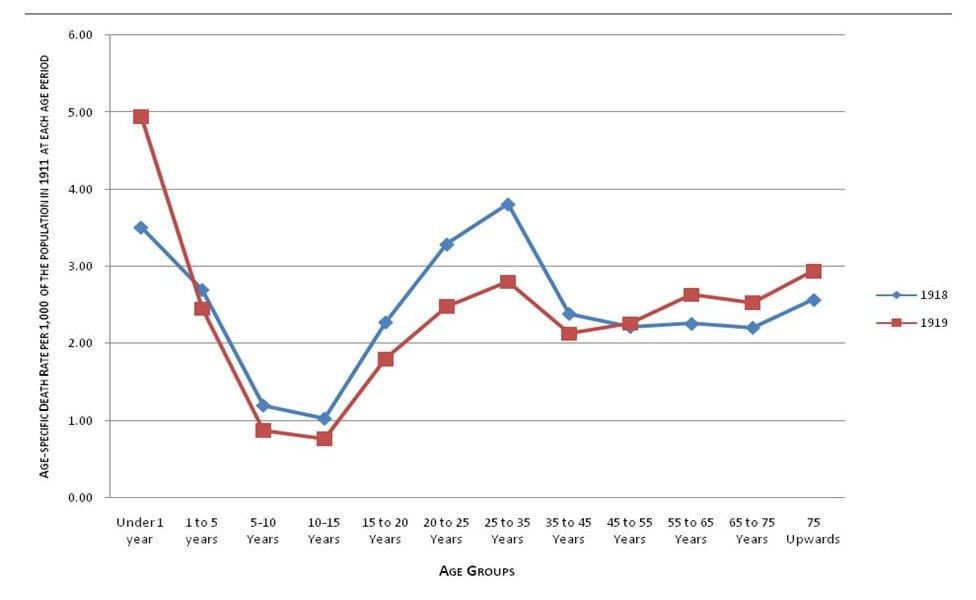

Unusually, the virus also affected the 20-40 age group more than any other section of the population, so "strong, young adults, parents and workers, were wiped out by it", said Dr Marsh.

To make matters worse, many doctors and nurses had been killed while working on the Western Front, so the medical industry was not fully equipped to deal with another disaster.

Public places, such as cinemas and schools, were closed to prevent the spread of the flu and people were advised to keep their hands clean and to refrain from spitting.

Archive advertisements associated with flu and remedies

According to Dr Marsh, Belfast was the first location in Ireland where signs of Spanish flu were detected.

From there, it spread across the rest of Ireland, thriving in densely populated towns and cities; factories, where workers gathered in close quarters, encouraged the virus to spread.

"Newry also had a high mortality rate, which remains more of a mystery, but the nearby port, with its merchant ships, could have been the reason as to why the death rate was so high," said Dr Marsh.

"It was recorded as returning to Northern Ireland on 9 October in Larne - probably because of the harbour."

Figures calculated from the 55th and 56th detailed annual report of the Registrar-General Ireland

Despite being a rural farming area, County Donegal also experienced great losses.

According to Dr Marsh, the Catholic tradition of holding wakes for the deceased is likely to have been a primary cause of death within the county.

"Many believed an infected corpse would have been contagious, but it was actually the gatherings in confined spaces that would have caused the spread," she explained.

"Many members of the farming community died in Donegal. If one infected person entered a small cottage at an event such as a wake, the disease would spread like wildfire."

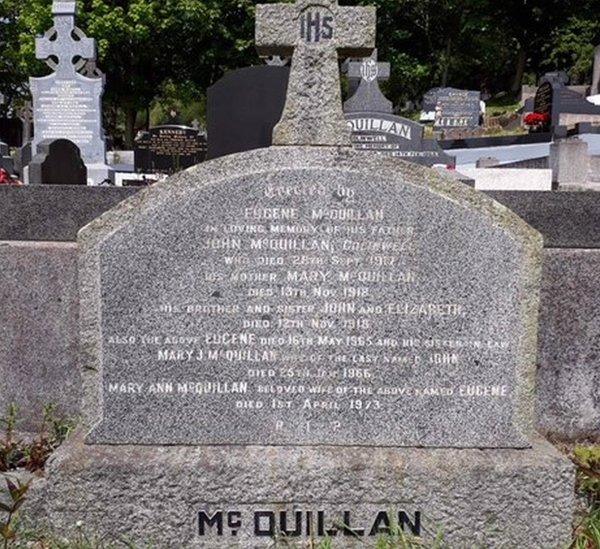

Rosaleen McQuillan Crilly, whose family descended from Hannahstown village on the outskirts of Belfast, has some knowledge of the horror the virus caused.

Her father, John McQuillan, was born in September 1918.

"Tragedy struck the McQuillan family when my father was eight weeks old, as they were caught by the epidemic that was sweeping across Europe," she said.

Triple funeral

"My grandfather, Johnny, died from the flu on 12 November 1918, aged just 30 years. His sister, Elizabeth, passed away the very next day, aged just 32 years, as well as their mother Mary, aged 58 years.

"Both granddad and Elizabeth's death certificates state the cause of death to be influenza and septic pneumonia, and great-grandmother Mary's stated influenza and heart failure."

Their gravestone is a subtle reminder of just how badly the 1918 influenza pandemic devastated both society and communities in the post-World War One world.

Today, there remains no official commemoration site marking the pandemic and it is rarely included in school history curriculums.

However, evidence of the lives lost can be found on gravestones, in obituaries, in newspapers and within stories passed down through the generations.

The McQuillan family tombstone

"There was death everywhere," said Dr Marsh.

"When you think about 23,000 deaths in Ireland in the space of nine months - more than the total for the War of Independence that followed - when you think about whole families dying together, countless children left orphaned across Ireland, the horror of that is quite unimaginable in this day and age."

*This is an amended version of the original report. The reference in the second paragraph to the number of people who died in November 1918 has been corrected.

- Published15 October 2018