Spanish flu pandemic 1918 - could it happen again?

- Published

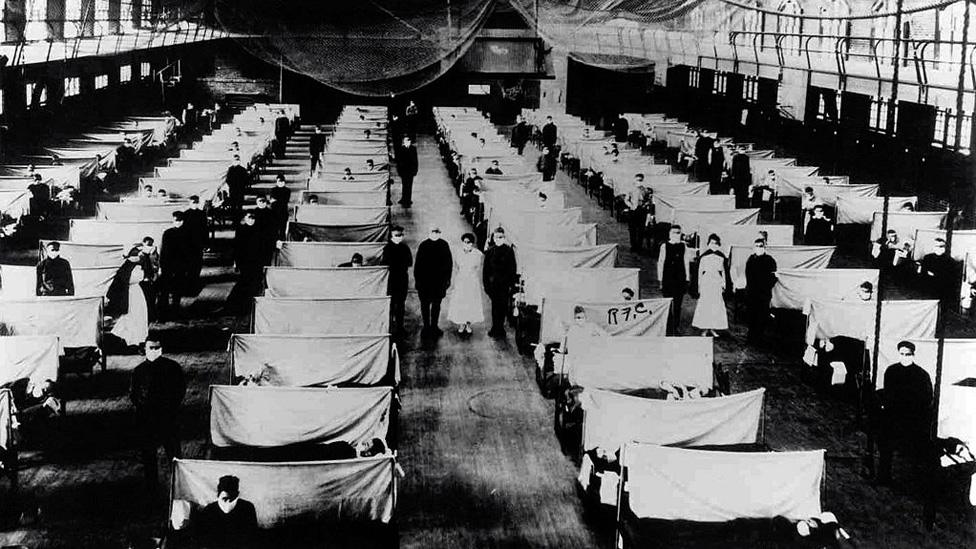

A warehouse being used as a makeshift hospital for flu patients in 1918

It is 100 years since the influenza pandemic killed millions around the world, a death toll far worse than the bubonic plague. But what is the chance of something similar happening again? New strains of flu continue to emerge and experts warn that another pandemic could happen despite a century of advances in technology and healthcare.

During the 1918-19 outbreak, it was thought that Spanish flu was caused by bacteria rather than a virus. Viruses are now better understood, but scientists have also learned a great deal from studying the pandemic which struck a century ago.

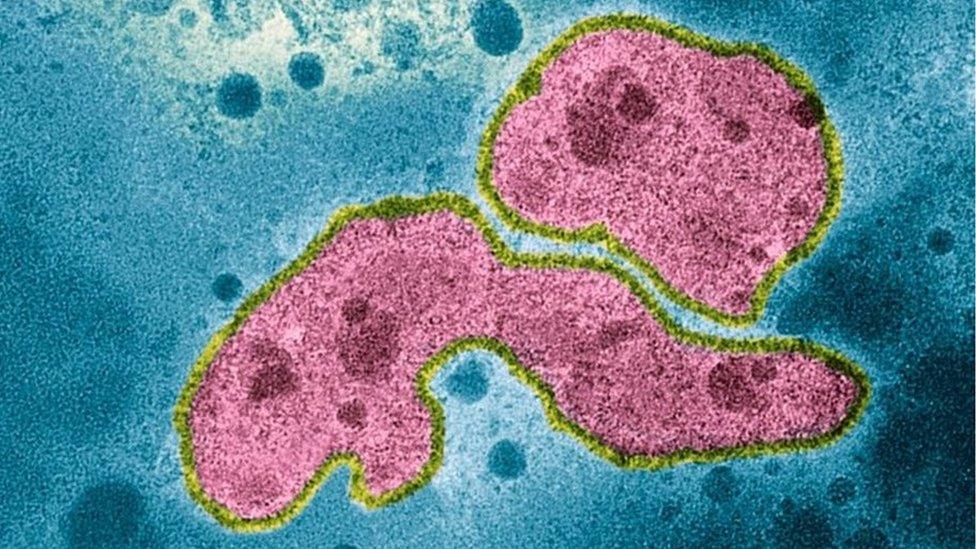

A coloured transmission electron micrograph of A strain H5N1

They learned how very differently it could behave to our usual experience of seasonal flu. It hit proportionately more younger and healthier adults. Experts believe older people who were infected by Spanish flu may have previously encountered a similar strain, and therefore had a degree of immunity.

Dr Niall Johnson, who published a study of the 1918-19 pandemic says the medical profession a century ago was familiar with infectious disease, but not at this scale.

"Many of the medical memoirs mention the pandemic, and often say that it was not the presentation of the disease that was unusual but the sheer volume of cases - and how little they could offer people," he said.

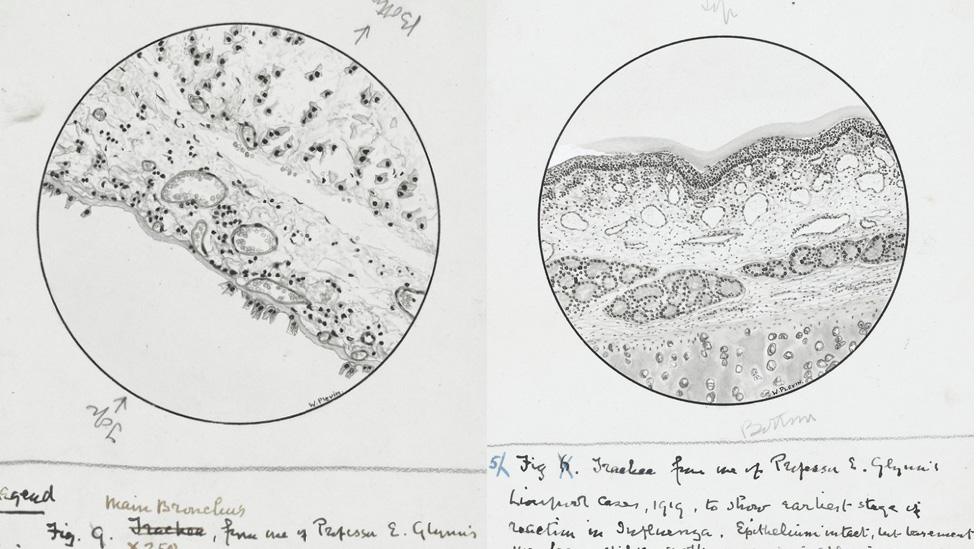

Drawings from 1918 by John George Adami of (right) the trachea showing earliest stage of reaction in influenza and (left) the main bronchus of a set of lungs

Dr Jonathan D Quick, external is an expert on epidemics worldwide and is working to help nations prepare better.

"With some flu viruses - it was true in 1918 and in 2009 - one of things which happens is that the way that flu kills you is not the flu itself," he said. "It's what it does to your lungs, it sort of melts the linings and then you get a bacterial pneumonia... that will kill you.

"They didn't have antibiotics then, so they died faster. But the other thing that happens, particularly in young people when they have a good, active immune system is that your body overreacts. It ends up just filling your lungs with fluid. A lot of these deaths weren't from the bacterial complications, but from an explosion of the immune system."

Dr Johnson says the impact of new viruses today will vary, for several reasons. These include vaccines that may confer some immunity, anti-viral drugs, better hygiene and antimicrobials that deal with the infections such as pneumonia, that were major contributors to the death rate in the 1918-19.

"So, yes, I think we are better placed than in 1918 but the potential for a pandemic to be a global infection that sickens the majority of the world's population and kills a substantial number is still there."

Dr Quick believes such a scenario is not inevitable, if more is done to make the world safer and prepared.

"One of the most important things is to invest in the so-called universal flu vaccine," he says - one which works against all strains of the virus, by targeting the part of the virus which doesn't change.

More stories you might be interested in

The UK government sets out an official National Risk Register, external, which says that no country is immune to infectious disease from another part of the world. It estimates that in the event of pandemic flu:

Up to half of the UK population could experience symptoms

This could potentially lead to between 20,000 and 750,000 fatalities and high levels of absence from work.

Dr Quick believes the UK is the only country to report risk in this way.

Dr Jonathan D Quick is asked are we complacent about the chances of a flu pandemic reoccurring

But globally, are we still complacent?

"Absolutely," he says. "I believe we're just as vulnerable today to big flu as we had in 1918 but for different reasons. So today we have four times the population, we are twice as urbanised, and that crowding has been a factor in recent Ebola outbreaks, and is a factor in flu.

"We are 50 times as mobile - so we're in the air, travelling across borders, there isn't any place on the planet which is more than 24 to 36 hours away from any major city."

He says flu is tricky, a virus that keeps mutating and exchanging genes.

"With all of those risk factors in play, we could have an epidemic with a new virus that has mutated and that we don't have immunity to," he says.

"We could have an outbreak which could kill between 200 and 400m in the matter of a couple of years and knock the global economy as badly as the Great Recession."

The experiment tracked people's movements and interactions to predict how a pandemic might spread

Predicting the path of a pandemic

The BBC Four Pandemic experiment, with mathematicians from Cambridge University, involved nearly 29,000 people downloading an app to track their movements and social interactions to predict how a pandemic might spread.

Their modelling predicted that:

43.3m in the UK could catch influenza in a pandemic, in a worst-case scenario

That worst case could mean 886,877 deaths over the course of 248 days.

The virus might spread more slowly, and to only three quarters of the predicted population if a regular hand-washing regime was employed.

Dr Meirion Evans, a recently retired consultant epidemiologist at Public Health Wales, believes the key is vigilance and sharing data - underpinned by a global surveillance system which is coordinated by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

"Linked to that is a global virology network... when there's an incident, the local specialist laboratory will isolate, identify and type these viruses to work out if it's something new, or if it's not, what virus it is related to," he said.

Technology could also help. Dr Quick points to the web crawler created by Public Health Canada which harvested news of the SARS outbreak as it showed itself in China.

Archive advertisements associated with flu and remedies

We have come a long way from old newspaper adverts, offering cure-all remedies, old wives' tales and simple hope. But there are lessons still to learn - and we underestimate flu at our peril.

"If anyone doubts it, humanity has not escaped infectious disease," says Dr Johnson. "In the mid-20th Century some people rather hubristically claimed we'd beaten infectious disease. HIV, multi-drug-resistant TB, flu, Ebola all put pay to that.

"Flu is particularly interesting due to its ability to change, and our continuing inability to find vaccines that work against more than specific strains".

It is impossible to tell when the next pandemic flu may occur - in 25 years or next year.

Although a rare occurrence, Dr Quick says in the meantime we must be ready for it at the highest level.

"There needs to be that vigilance and the willingness of leaders to open their eyes - because delays are deadly - respond to the immediate epidemic and then once the panic's gone, keep promises about investing in preventing the next one; it's that leadership."

- Published12 October 2018

- Published20 September 2018

- Published14 May 2018

- Published19 January 2018