Brexit: Does the Irish peace accord rule out a hard border?

- Published

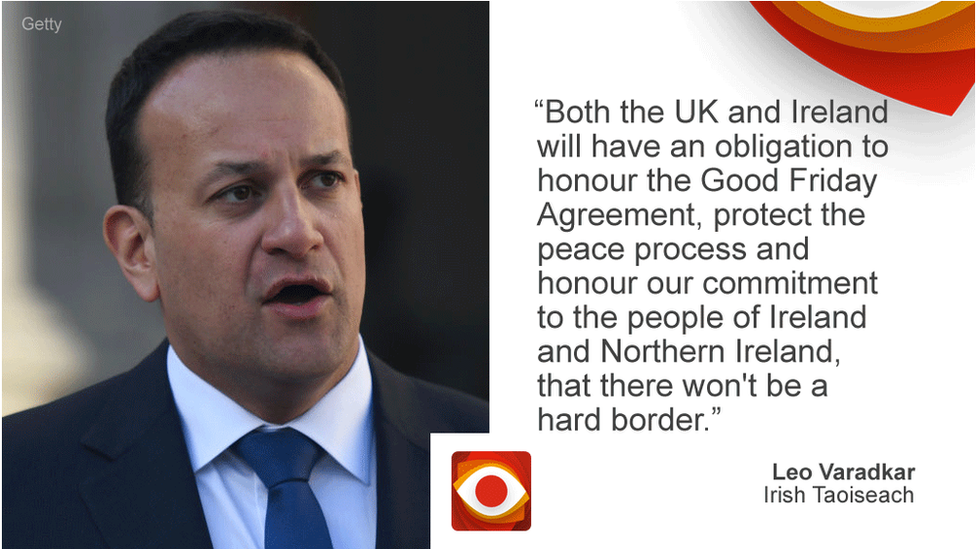

Taoiseach Leo Varadkar, the Irish prime minister, has told the Irish Parliament that the UK and Ireland must honour the Good Friday Agreement and honour their commitment not to have a hard border.

After Brexit, the border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic would become the only land border between the UK and the European Union. If there wasn't a deep enough trade deal between the UK and the EU, it would likely mean checks on goods which cross it.

That's where the backstop comes in - an insurance policy to avoid new inspections or infrastructure at the border - after Brexit.

It's a key part of Theresa May's Withdrawal Agreement - but a major reason why it was defeated in Parliament .

What is the Good Friday Agreement?

Also known as the Belfast Agreement, external, it is the deal that is widely seen as marking the effective end of Northern Ireland's "Troubles".

It established a devolved power-sharing administration, and created new institutions for cross-border cooperation and structures for improved relations between the British and Irish governments.

It was approved by referendums in Northern Ireland and Ireland in 1998 and was subsequently incorporated into British and Irish constitutional law and other areas of legislation.

The Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998

What does the Good Friday Agreement say about a hard border?

A lot less than you might think. The only place in which it alludes to infrastructure at the border is in the section on security.

During the Troubles there were heavily fortified army barracks, police stations and watchtowers along the border. They were frequently attacked by Republican paramilitaries.

Part of the peace deal involved the UK government agreeing to a process of removing those installations in what became known as "demilitarisation".

The agreement states that "the development of a peaceful environment... can and should mean a normalisation of security arrangements and practices."

The government committed to "as early a return as possible to normal security arrangements in Northern Ireland, consistent with the level of threat".

That included "the removal of security installations". That is as far as the text goes.

British soldiers on patrol on the Irish border in 1977

There is no explicit commitment to never harden the border, and there is nothing about customs posts or regulatory controls.

What about commitments in the agreement made by the two governments?

The agreement contains a commitment by the British and Irish governments to develop "close cooperation between their countries as friendly neighbours and as partners in the European Union" - of course, there was no inkling back in 1998 that the UK would vote to leave the EU 18 years later.

But there are no specific commitments about what that should involve in regard to the border.

The cross-border strand of the agreement lays out 12 areas of cooperation, which are overseen by the North-South Ministerial Council (NSMC).

It could be argued that a hard border would make that strand of the agreement more difficult to operate.

Additionally, a section on economic issues states that, pending devolution, the British government should progress a regional development strategy that tackles "the problems of a divided society and social cohesion in urban, rural and border areas".

It could be argued that a hard border would conflict with the spirit of that part of the agreement but again there is no specific prohibition.

Has this been legally tested?

No. The Good Friday Agreement featured in some of the Article 50 litigation, including the Gina Miller case, but the issue of a hard border was not addressed.

In his ruling in a 2016 case at Belfast High Court, Mr Justice Maguire suggested it was premature to assess how Brexit would affect the peace accord.

He said: "While the wind of change may be about to blow, the precise direction in which it will blow cannot yet be determined so there is a level of uncertainty, as is evident from discussion about, for example, how Northern Ireland's land boundary with Ireland will be affected by actual withdrawal by the United Kingdom from the EU."

What has the Irish government been saying?

Leo Varadkar has asserted that if there's a no-deal Brexit, the UK would still have to accept full regulatory and customs alignment in Northern Ireland as part of its obligations under the Good Friday Agreement.

Irish ministers have tended to focus more on the "spirit" argument rather than making specific legal claims.

For example, last year Foreign Minister Simon Coveney wrote that the agreement had removed "physical and emotional" barriers between communities in Ireland.

He described "the genius" of the agreement as providing a framework for "all of the relationships on our two islands - between communities in Northern Ireland, between north and south on the island of Ireland, and across the Irish Sea."

What exactly is the 'spirit' of the Agreement?

That is open to interpretation but is widely understood to be a spirit of non-violence, consent and partnership.

Theresa May's 2018 White Paper on the future relationship with the EU (the Chequers plan) spoke of the need to honour "the letter and the spirit" of the Agreement.

However it doesn't elaborate on what that "spirit" might be.

Sinn Fein's Mary Lou McDonald and Michelle O'Neill knocked down a mock hard border at a demonstration over the weekend

Katy Hayward, Reader in Sociology at Queen's University Belfast, says that while a hard border does not in itself challenge the agreement it's "fair to say" the assumption behind the Good Friday Agreement was one of "closer integration".

"Avoiding a hard border has been put at the heart of this process as a priority for both the UK and EU because they recognise the symbolism of the current openness of the border."

Her research has involved a large-scale study of views on Brexit from local communities in one border region.

She found that people living in that area see what happens at the border as being "a bellwether for the quality of peace".

"They see the increasing openness of the border in the past two decades - and the economic and social benefits of that - as being entirely a consequence of the 1998 Agreement.

"This is why, to add any restriction or friction to what people currently take for granted when crossing the border is seen in their minds as a sign that the peace process is going backwards, and that the 1998 Agreement is being undone."

What do others say?

Northern Ireland's Chief Constable, George Hamilton, has repeatedly said that a hard border would be damaging for the wider peace process.

He has said that any new border infrastructure would be seen as "fair game" for attack by dissident republicans.

In an interview last year, he also put the border in the context of the Good Friday Agreement.

"If you put up significant physical infrastructure at a border, which is the subject of contention politically, you are re-emphasising the context and the causes of the conflict," he said.

"So, that creates tensions and challenges and questions around people's identity, which in some ways the Good Friday Agreement helped to deal with."

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and some Brexit-supporting Conservative MPs say the issue of a hard border need not arise as they believe it can be overcome by a range of administrative and technical measures.

The DUP also says the real threat to the spirit of the Good Friday Agreement is the imposition of the backstop.

Sinn Fein has said any hard border in Ireland will lead to further calls for a referendum on Irish unification and is pushing for a border poll to be held in Northern Ireland if there is a no-deal Brexit.

- Published15 November 2018

- Published13 September 2019

- Published9 April 2018