Contaminated blood inquiry: 'Four-year wait' to be told of hepatitis C

- Published

Simon Hamilton gave evidence on Wednesday

A man has told the contaminated blood inquiry that health officials knew he had tested positive for hepatitis C four years before he was informed.

Hearings into what has been called "the worst treatment scandal" in NHS history opened in Belfast on Tuesday.

Some 4,800 people across the UK were infected with with hepatitis C or HIV in the 1970s and 1980s. More than 2,000 are thought to have died.

Simon Hamilton gave evidence on Wednesday.

He said he felt like he was the "last to know" about his case.

The inquiry heard that health officials knew he had hepatitis C in 1990 but that he was not informed he had the virus until 1994.

A letter in his medical notes in 1990 had indicated that he had hepatitis C.

He said it "causes me concern" that he felt he was "the last to know despite my fundamental right to information".

In 2010, Mr Hamilton learned he had cirrhosis of the liver and, as a consequence, has had to be tested every six months for the rest of his life.

Witnesses from Northern Ireland are speaking at the inquiry this week

He described that as a process for which he was grateful but said it made him "anxious" as he was aware doctors are testing him for liver cancer.

The 58-year-old was emotional as he outlined being treated for a brain haemorrhage.

He described seeing his wife crying in a hospital corridor as a "very serious moment".

"It was the first time I felt I know what it was like to accept death and be willing to do that."

He also told the inquiry about a letter that he said had been sent from his consultant to his GP that revealed that 98% of all haemophiliacs who were treated with infected blood during or before 1985 would be told they are positive for hepatitis C.

Mr Hamilton made reference to issues he had around dental treatment - he said something said by one of the witnesses on Tuesday had resonated with him.

"I felt dirty, unclean, guilty of something I hadn't done because of the reaction of other professionals who refused, simply refused to take X-rays," he said.

Asked by counsel about the "particular burden" he had described his mother feeling, he said she and another relative who had lost two family members "would share the guilt".

"Mothers have a special something and for them the burden of guilt is considerable," he said.

"My mother is 85 and she still feels that guilt.

"That scar is there. It is like a brand."

Danielle Mullan also gave evidence to the inquiry.

Her mother, Marie Cromie, found out she had hepatitis C in 2005 and has had to undergo two liver transplants.

Mrs Mullan confirmed that her mother had been given a blood transfusion after childbirth.

She was shown a medical document from November 1981 upon which was noted in handwriting "picture suggestive of infective hepatitis".

Asked by counsel for the inquiry if her mother was ever told of this, Mrs Mullan said "no, the first we saw of this test result was when we obtained her medical records".

Mrs Mullan said she had told some school friends about the hepatitis C diagnosis as it "didn't seem as severe as what I know now".

"It started to become apparent that some kids wouldn't stand too close to me," she added.

"Some of them wouldn't touch a bottle.

"They wouldn't pass a ball to me in netball. It was like I had become some kind of leper."

Fighting back tears, Mrs Mullan described how her mother had suffered after having a transplant which had initially appeared to be successful.

"I remember her sitting and telling me in the living room one night if they came back and told her she needed the second liver transplant she couldn't do it again.

"It was too much."

Mrs Mullan ended her testimony by thanking the inquiry chair, Sir Brian Langstaff, for bringing the inquiry to Belfast.

"To everyone who is involved in this inquiry - you are not alone, we are in this together and no matter what we will get the answers that we deserve."

The inquiry is looking at why thousands of people with haemophilia were infected with hepatitis C or HIV in the 1970s and 1980s.

With allegations of a cover-up, no-one in government or the NHS has been held to account.

Some people have waited 30 years for a full public inquiry.

What is the scandal about?

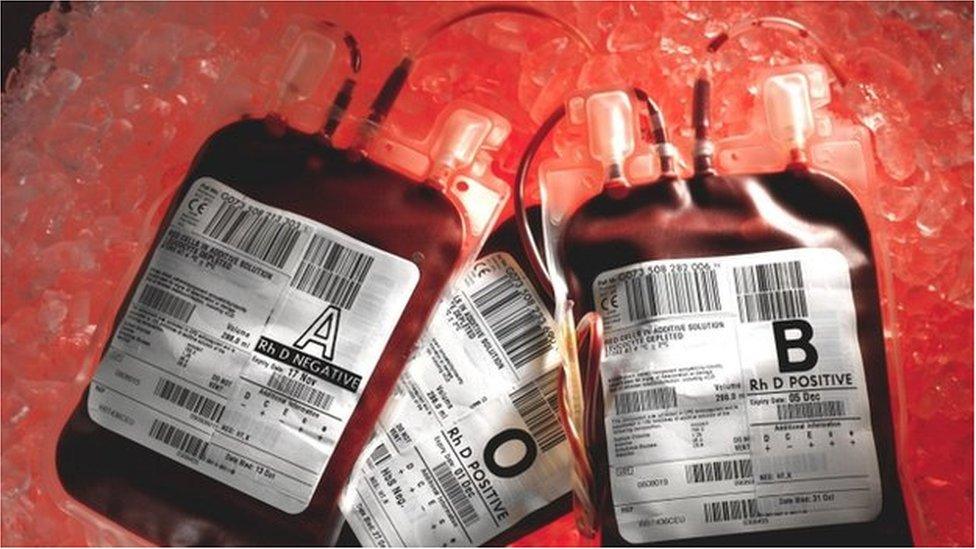

About 5,000 people with haemophilia and other bleeding disorders are believed to have been infected with HIV and hepatitis viruses over a period of more than 20 years.

That was because they were injected with blood products used to help their blood clot.

It was a treatment introduced in the early 1970s - before then, patients faced lengthy stays in hospital to have transfusions, even for minor injuries.

The UK was struggling to keep up with demand for the treatment - known as clotting agent Factor VIII - and so supplies were imported from the US.

But much of the human blood plasma used to make the product came from donors such as prison inmates, who sold their blood.

Factor VIII was imported from the US in the 1970s and 1980s

The blood products were made by pooling plasma from up to 40,000 donors and concentrating it.

People who had blood transfusions after an operation or childbirth were also exposed to the contaminated blood - as many as 30,000 people may have been infected.

By the mid-1980s, the products started to be heat-treated to kill the viruses.

But questions remain about how much was known before that and why some contaminated products remained in circulation.

Screening of blood products began in 1991.

By the late 1990s, synthetic treatments for haemophilia became available, removing the infection risk.

- Published21 May 2019

- Published20 May 2019

- Published30 April 2019

- Published24 September 2018

- Published30 April 2019