Northern Ireland ceasefires: 25 years of imperfect peace

- Published

Brian Rowan at a peace wall in Belfast

On 31 August 1994, the IRA called its first ceasefire - the beginning of the end of a violent campaign that had already stretched into its third decade. By October that year loyalist paramilitaries had followed suit. Brian Rowan was a BBC NI correspondent at the time and 25 years on, he asks how much progress has been made?

When we first read the ceasefire statements in 1994, could we have predicted the political and legacy wars of today - the latter being the long fight for the truth about the years of conflict?

Add to this the battle that is Brexit.

In the hope of 1994, is this what we expected?

Twenty-five years later, the political landscape and conversations are changing - and the ceasefires are but a moment in history.

With the wisdom of hindsight, we know they were the beginnings of an imperfect peace - not an end.

There were other phases of murder; new threats posed by the many and various types of dissident IRA. Those threats have again been evident in recent times.

Reporting the 1994 IRA ceasefire

The current security and intelligence assessment is that all of the organisations that were part of the conflict or "Troubles" period continue to exist in some shape or form; some more obvious than others.

They did not disappear in the peace.

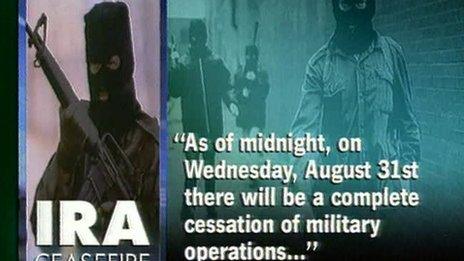

The ceasefire statements of 1994 seemed to offer so much more - firstly, in August, the IRA declared a "complete cessation of military operations".

The roots of Northern Ireland’s Troubles lie deep in Irish history

Then, in October, the response came from the Combined Loyalist Military Command (CLMC), an umbrella group for loyalist paramilitaries, which included the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Red Hand Commando. At a news conference in Belfast, the former UVF leader Gusty Spence read a statement saying that they would cease "all operational hostilities".

Loyalist representatives announce their ceasefire in 1994

After the slaughter of two-and-a-half decades, which had claimed more than 3,500 lives, at last there was a moment to dream and to hope.

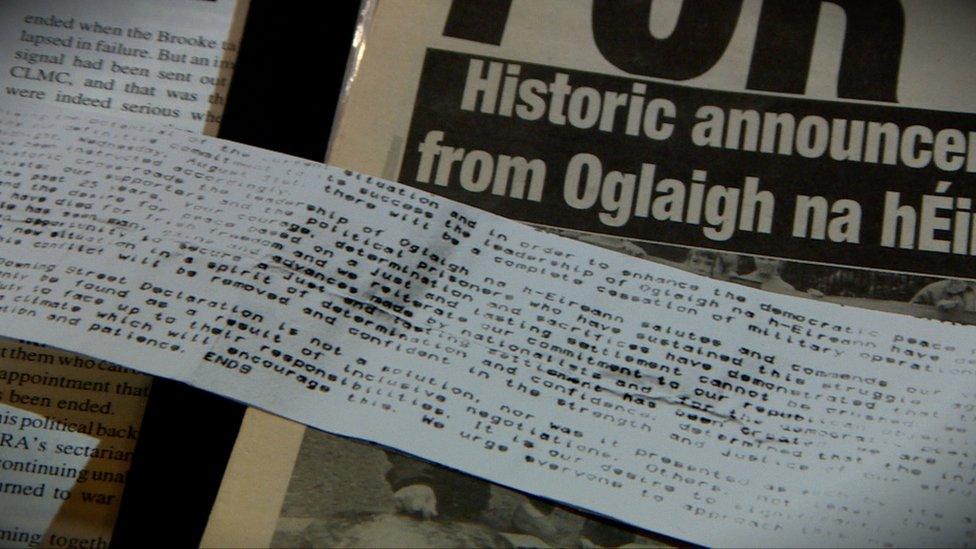

Working then as a BBC correspondent, I was called to a meeting on the morning of 31 August, where a woman read this IRA statement to me.

A copy of the IRA statement read to Brian Rowan

And, the night before the announcement by the CLMC, I met senior loyalists and was given a statement by the former UVF leader Gusty Spence pointing to an "unprecedented press conference" the following morning. The stage was being set for a new day.

Now, to mark the 25th anniversary of those ceasefires, I have conducted a range of interviews; assessing the worth of 1994 through the lens of 2019.

'The war was over'

Jake Mac Siacais - son-in-law of the late IRA leader Brian Keenan - was twice jailed in the period spanning the mid-1970s through to the early 1980s.

Inside the Maze Prison in 1981, he wrote and delivered the oration for the hunger striker Bobby Sands; reading it from a cell he shared at that time with the IRA jail leader Brendan McFarlane.

Stormont stalemate 'isn't about an Irish language act'

Today, Mac Siacais is a prominent figure in the Irish language community and director of a project developing the Gaeltacht Quarter in Belfast.

He has deep background knowledge of the internal republican debate which led to the IRA ceasefire.

Sinn Féin supporters celebrate the ceasefire announcement

Looking back, he says that a different approach should have been taken by republicans: "The war was over and we should have said the war was over."

The former prisoner also believes that the IRA leadership should have given an order for its arms to be "permanently dumped".

He means that the weapons should have been buried by the IRA itself and not subjected to a protracted negotiation over decommissioning in which an international commission supervised the arms being put beyond use.

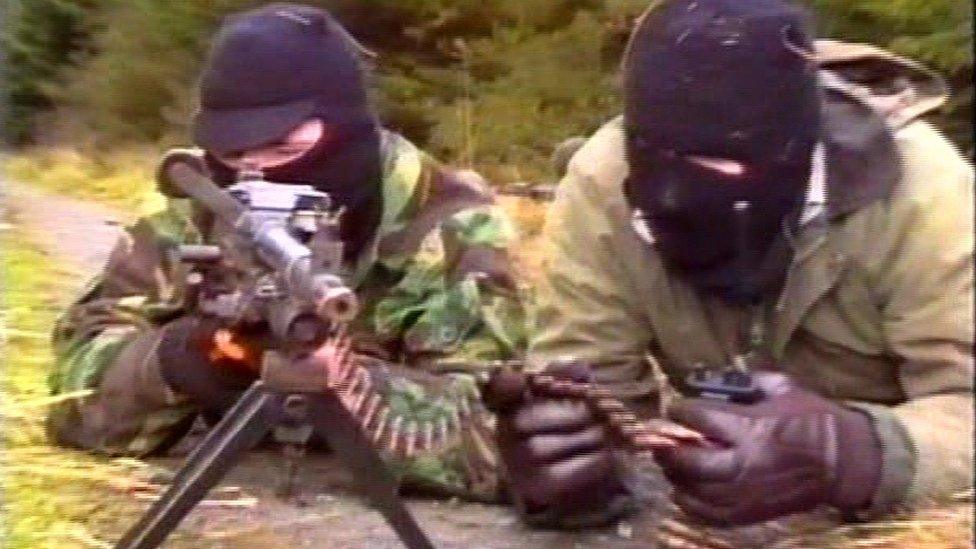

Still from an IRA propaganda video

The IRA became a bargaining chip in those decommissioning arguments and in the post-Good Friday Agreement manoeuvres for a new government at Stormont.

The Mac Siacais argument will be viewed as a narrow republican one. Any political agreement was always going to include the demand for illegal weapons to be destroyed.

Irish identity

In the here-and-now, politics has moved beyond the decommissioning issue, but there are new arguments which brought about the collapse of the power-sharing government at Stormont in January 2017.

Those disputes, including the demand for an Irish language act, still divide the big two parties - the Democratic Unionist Party and Sinn Féin.

I asked Mac Siacais if there could be a restoration of the political institutions without such an act? "Well, of course there can be, but there shouldn't be," he replied.

He added: "It isn't about an Irish language act. It's about the ability or inability of unionists and the northern state to recognise or make explicit the recognition of the legitimacy of an Irish identity, which, when we think of it, was at the heart of the entire conflict."

Is the union safe?

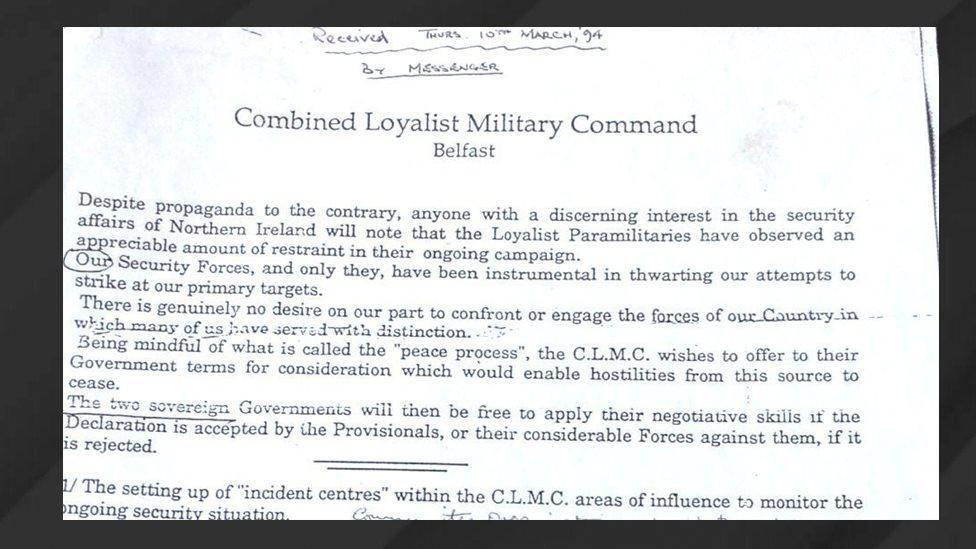

Retired Church of Ireland Archbishop Lord Eames played a key background role in the events that led to the loyalist ceasefire announcement, including speaking to then Prime Minister John Major and Taoiseach Albert Reynolds.

Loyalists had given the churchman a set of conditions which, if met, would allow their ceasefire to be announced first. This is the document - not published at the time, but obtained later.

Loyalists paramilitaries gave a statement to Lord Eames

Events on the ground - the targeting and killing of prominent loyalists - meant the initiative was derailed. When the ceasefire was eventually announced, it was delivered in the firm belief that the union between Great Britain and Northern Ireland was safe.

'Danger signs'

Twenty-five years on, Lord Eames believes that the looming prospect of Brexit is changing dynamics across the islands and old certainties are being eroded.

Surveying today's bleak political landscape, he told me: "I'm praying that the spirit of the ceasefire days could possibly infiltrate political life today."

I asked him if the union was still safe in 2019. "I would like to say it is, but I believe that there are danger signs which I think we all need to be conscious of."

Lord Eames

The frame of the political debate in Northern Ireland is widening. No longer is it just about devolution at Stormont or direct rule from Westminster, but what a "new Ireland" might look like and how it might embrace unionists.

Lord Eames said: "New thinking is welcome. You don't have to surrender your principles or the principles you have been brought up on to simply grasp new ideas.

"I'd like to know a bit more about what is meant by the 'new Ireland', but I can see possibilities."

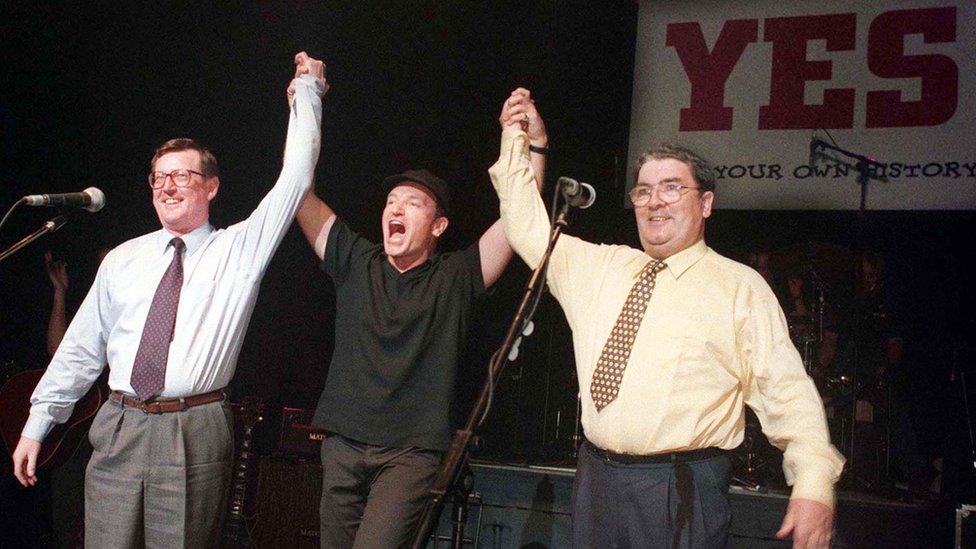

David Trimble and John Hume on stage with U2's Bono in 1998

Legacy war

A decade ago in 2009, Lord Eames helped to produce the first report aimed at establishing a process to address the questions from the conflict period.

His team proposed the setting up of a Legacy Commission and, most controversially, a £12,000 payment to the relatives of all those killed in the conflict.

But 10 years on, the waiting for such a process continues and we are watching a legacy war - a fight for the past in which the trenches are being dug deeper.

The Stormont House Agreement of 2014, which included proposals for a new Historical Investigations Unit (HIU), has resulted in further disagreement.

Truth recovery

Tommy Quigley watches the debate around legacy with keen interest.

He is a former IRA life sentence prisoner who is still on licence following his release.

His brother Jimmy, who was also an IRA member, was shot dead by the Army in Belfast in 1972. The Quigley family is still searching for answers about the circumstances of the killing.

Former IRA prisoner Tommy Quigley

Tommy Quigley believes that a legacy process is needed where people are willing to come forward - and that can only happen with an amnesty.

"I don't see why anyone from any background would come forward and give evidence or give information if they thought they were going to be prosecuted, or even if there was a chance that they were going to be prosecuted," he said.

Disappearing knowledge

In the waiting for some resolution of the past, memory is dying out.

The IRA leaders Martin McGuinness, Brian Keenan and Kevin McKenna are no longer with us.

Nor are the unionist leaders of the ceasefire period - James Molyneaux and Ian Paisley.

Some who played key interlocutor roles, including the priest Father Alec Reid, the Presbyterian minister the Rev Roy Magee and businessman Brendan Duddy, who for decades was a back channel link between the British Government and the IRA leadership, are dead.

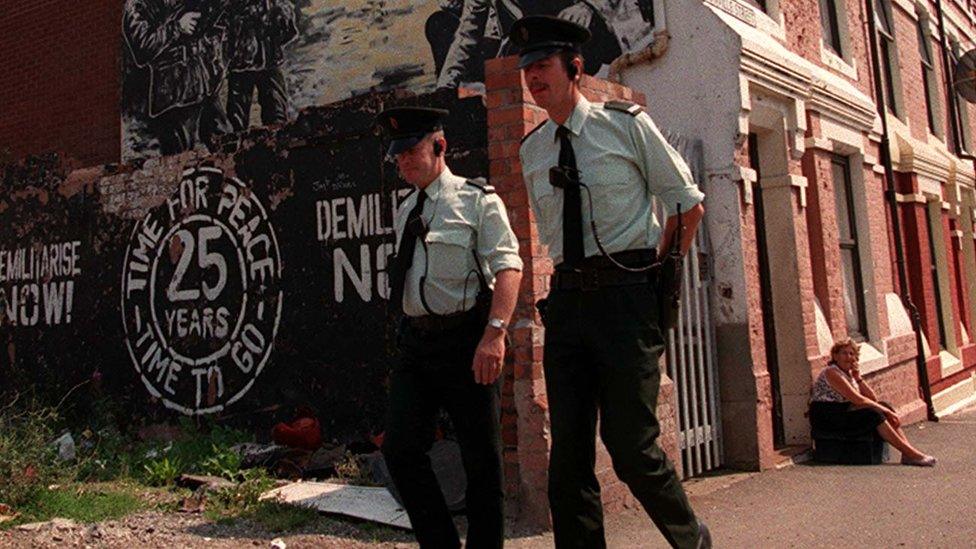

RUC officers on patrol in west Belfast

So too the taoiseach (Irish prime minister) in the ceasefire period Albert Reynolds and the then Northern Ireland Secretary of State Sir Patrick Mayhew.

Four of the seven men who sat at the top table when the loyalist ceasefire was announced - Gusty Spence, Jim McDonald, David Ervine and William 'Plum' Smith are dead.

Information, knowledge, memory - all now lie buried in the peace.

The widows

Ervine and Smith were themselves both former prisoners, who went on to play key roles in persuading the paramilitaries to call a ceasefire and to allow their representatives to enter the negotiations that brought about the Good Friday Agreement.

I have been speaking to their widows Jeanette Ervine and Liz Smith about the past and how it fits into the present; specifically about historical investigations continuing 25 years after the ceasefires.

Jeanette Ervine and Liz Smith

Jeanette Ervine said: "I can feel for the victims of the Troubles, but I don't think that bringing somebody back to prison is going to do any good.

"These people are already hurting and I don't think that will salve that."

She added: "That was part of the Good Friday Agreement - the prisoners would be released...there wasn't a clause to say when they're 60 or 70-years-old we're going to come back and convict them and put them back in there for end of their day."

Ed Spence, nephew of Gusty Spence, who read the loyalist ceasefire statement in 1994, said that the late UVF leader would be very saddened at the lack of progress since.

He said his uncle saw the ceasefires as "the start of the finish of the war".

"25 years on, we are still at it," said Ed Spence.

An unfinished peace

The ceasefires of 1994 seem such a long time ago. They changed this place. Many lives were saved.

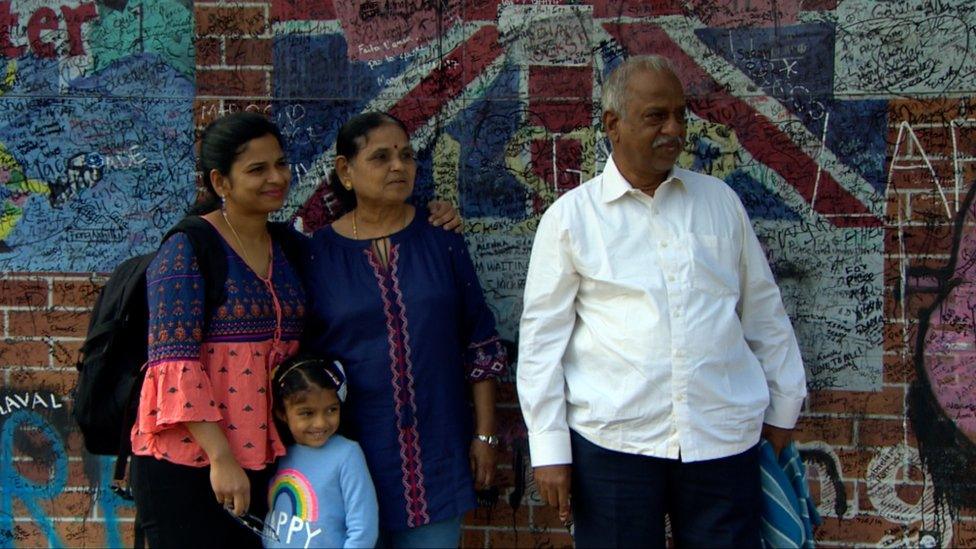

A family visits a Belfast peace wall

Every day, the so-called peace walls are visited and photographed. They are a statement of continuing division and a reminder of an unfinished peace. The scars of conflict are an open wound.

Politics has not been able to cement its place in the peace. There is no certainty about the future of Stormont and seemingly endless political negotiations continue.

It is much easier to analyse the past than to predict the future. Where will we be 25 years from now?

- Published31 August 2014

- Published27 August 2014

- Published29 August 2014