VJ Day: How a Belfast doctor used Irish to keep WW2 secrets

- Published

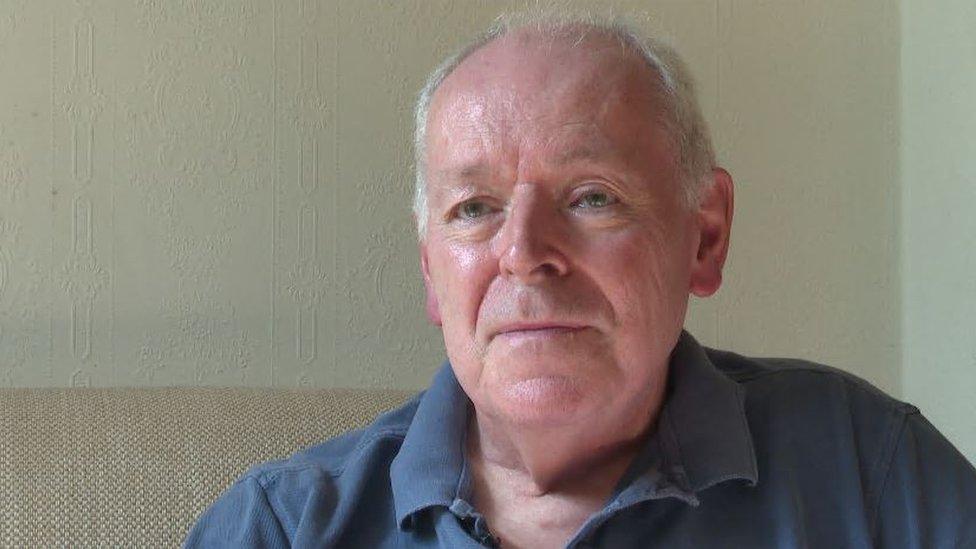

Dr Frank Murray was an Allied prisoner of war in a Japanese prison camp during World War Two

He became known as the Belfast Doctor and his medical expertise, leadership and guile helped protect the lives of hundreds of Allied prisoners of war in Japanese prison camps.

Frank Murray was born above the family spirit-grocers shop on north Belfast's Oldpark Road, growing up in a nationalist area of the city in a family with a strong Catholic faith.

Like many of his contemporaries, as a schoolboy he spent the summer in the Gaeltacht in Donegal learning the Irish language, something he would later use to his advantage thousands of miles away in the Far East during a world war.

His son Carl recounts how his father and mother first met among the peaceful and picturesque rolling hills of County Donegal before the outbreak of World War Two.

"My father met my mother Eileen O'Kane in the Gaeltacht area in Ranafast when they were both school children in 1929," he said.

Carl Murray said his father never forgave the Japanese military for what they did during the war

"She was from the Springfield Road and he was from the Oldpark Road in Belfast.

"He asked her to dance at a céilí and fell in love with her.

"They kept up contact thereafter and both went to Queen's University but in 1937 she broke things off and they had no further contact until he found himself in Rawalpindi in what was India at the time, where he was serving as an Army medical officer.

"He sent her a Christmas card with a picture of the officers' mess on it."

'Secret diaries'

The two began corresponding again and this continued when he was sent to the British garrison at Singapore.

All of her letters were lost when Dr Murray burnt them just before the Japanese invaded and took him prisoner.

However, the family have all the correspondence he subsequently wrote to his sweetheart while he was in captivity and it is these "secret diaries" that make such a fascinating story.

Carl explains that his father kept writing to her in the form of a diary but in order that he didn't incur the wrath of the Japanese guards he did so in Irish, safe in knowledge that the chances of any of them being able to translate were slim in the extreme.

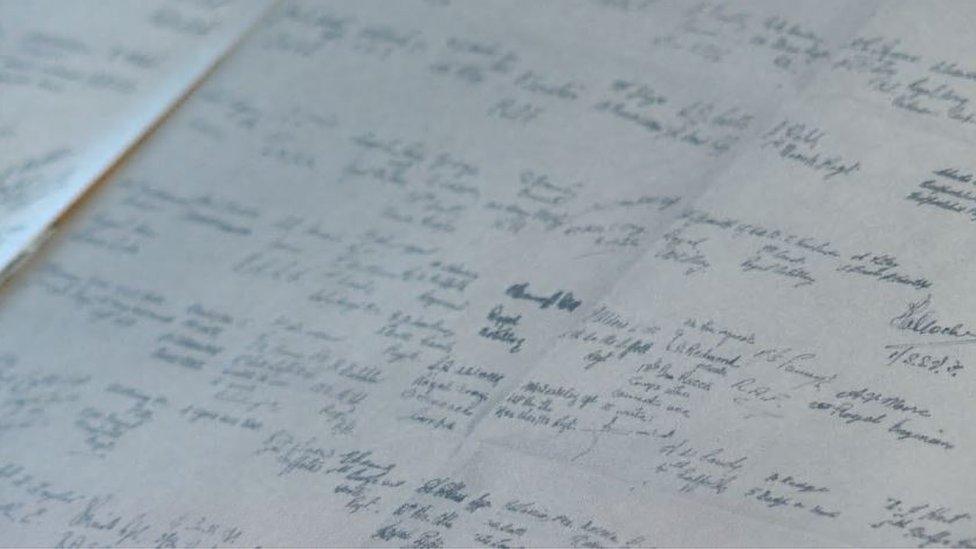

Letters Dr Frank Murray sent were sometimes in Irish, and sometimes used Irish characters

"Sometimes he would write in English but disguising it using old Gaelic script.

"I remember when I did Irish at school there were text books that had the old script in it which meant there was that extra level that you had to translate from the script and then translate the Irish.

"And he would write about how the war was going but by doing so in Irish he knew that even if the Japanese found it, there was very little chance of them being able to translate that he was recounting events that were happening during the war."

'He never forgave'

Keeping diaries of this kind was strictly forbidden particularly as the enemy soldiers were wary of prisoners recording incidents of brutality or war crimes against them.

Prisoners caught in breach of the regulations were liable to severe punishment in many instances.

Carl says after the war his father would not have anything Japanese in the house.

"I know it's fashionable to talk about reconciliation and forgiveness but I don't really think he ever forgave the Japanese, not for what happened to him but for the way the prisoners were treated.

"However, he distinguished between the Japanese military and the Japanese people.

"You have to respect that having been through what he went through. My father couldn't forgive and I think that's important."

The Murray family has collated as much information as they can about their father's time as a PoW.

'He wanted to do his bit'

He was the medical officer in a number of camps eventually becoming the most senior officer commanding in one prison.

His ability to argue or negotiate with his captors about who was fit and who wasn't fit to join the work details meant the difference between life and death for many Allied captives.

His bravery and service during this time was later recognised with an award from the US military and an MBE.

Documents kept by Dr Frank Murray's son Carl tell a remarkable story

So how did a Catholic nationalist from north Belfast end up a major in the British Army?

"As children we always wanted to know why he joined up," recalls Carl Murray.

"My father felt that the Nazis could easily have invaded Ireland at that time and later we discovered there was a plan to do that.

"He felt that as a northern Irish Catholic he wanted to do his bit in the war effort. I think he wanted to go to France but he ended up in India, the Malay peninsula and eventually Japan.

"It wasn't what he expected but he did his duty."

Astonishingly, the batch of almost translucent papers with tiny spidery writing that make up the doctor's daily diaries - which he kept right under the noses of his Japanese guards - was eventually delivered to Eileen at the end of the war.

When he was repatriated, the couple were married.

- Published15 August 2015

- Published5 August 2020