NI riots: What is behind the violence in Northern Ireland?

- Published

The rioting has mostly involved gangs of youths armed with bricks and petrol bombs

Nearly 90 officers have been hurt in Northern Ireland's worst street violence for years, after sporadic rioting in several towns and cities since the end of March.

The governments in Belfast, London and Dublin have condemned the unrest, with the US calling for calm as police used water cannons for the first time in six years.

Eighteen people have been arrested and 15 charged after crowds of predominantly loyalist youths attacked lines of riot police officers and vehicles with bricks, fireworks and petrol bombs.

Saturday night was the first without major incident since Good Friday on 2 April, with the lack of trouble being linked to the death of the Duke of Edinburgh.

While all Northern Ireland's main parties have condemned the violence, they are divided about its causes.

Where has the violence been happening?

Since the end of March, there has been unrest on a near-nightly basis, mainly in loyalist areas of a number of towns and cities

Violence involving gangs of youths started on 29 March in an area of Londonderry that is loyalist - in favour of keeping Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom.

Until the death of Prince Philip on 9 April, there were protests and rioting on a near-nightly basis in a number of towns and cities, including Belfast, Carrickfergus, Ballymena and Newtownabbey.

The areas affected are among the most deprived in the country, with the lowest level of educational attainment in Europe, external.

On the night of 7 April, the fighting spilled over a so-called peace wall in west Belfast that divides predominantly Protestant loyalist communities from predominantly Catholic nationalist communities who want to see a united Ireland.

A gate that divides the two was smashed open and, during several hours of disorder, police officers and a press photographer were attacked and a bus was hijacked and burned.

The clashes raised concerns of escalating sectarian tensions.

Parts of Northern Ireland are still split along sectarian lines, 23 years after a peace deal largely ended Northern Ireland's Troubles - which lasted almost 30 years and cost the lives of more than 3,500 people.

Who is behind the unrest?

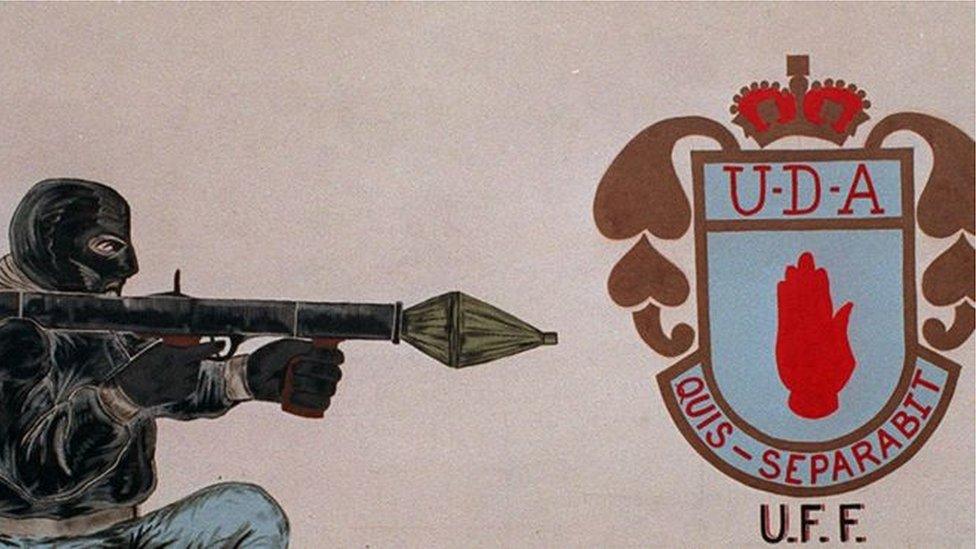

While there are no clear indications the unrest is being orchestrated by an organised group, the violence has been concentrated in areas where criminal gangs linked to loyalist paramilitaries have significant influence.

The violence has been concentrated in areas where loyalist paramilitaries have significant influence

There is increasing evidence that senior figures in organisations such as the Ulster Defence Association and Ulster Volunteer Force are allowing the trouble to proceed.

Analysts suggest loyalist paramilitaries of the South East Antrim UDA may have exploited an opportunity to kick back at the Police Service of Northern Ireland after a recent clampdown on criminality in the area around Carrickfergus.

Some of the unrest has involved adults egging on children to get involved in violence

The paramilitary group is involved in many forms of organised crime, doing "untold damage to the community and exerting fear in neighbourhoods", say police.

Northern Ireland's children's commissioner said adults engaged in "criminal exploitation" of fighting youths "had to be held accountable".

Koulla Yiasouma said the violence involved "coercion by adults of vulnerable and at-risk children".

Read more: 'A criminal cartel wrapped in a flag'

What has this got to do with Brexit?

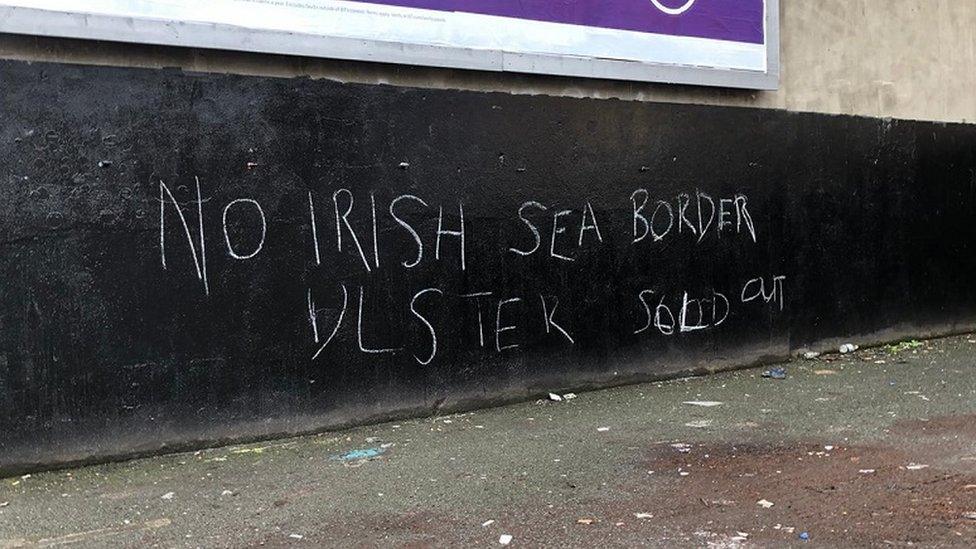

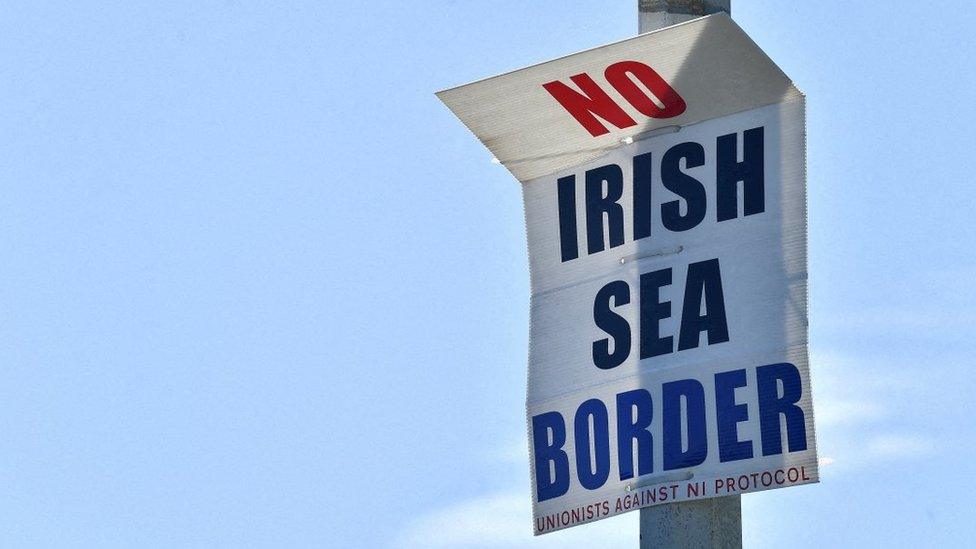

Unionist leaders have linked the violence to simmering loyalist tensions over the Irish Sea border imposed as a result of the UK-EU Brexit deal.

The new trading border is the result of the Northern Ireland Protocol, introduced to avoid the need for a hard border on the island of Ireland.

Unionists say the protocol damages trade and threatens Northern Ireland's place in the UK

The protocol means Northern Ireland remains in the EU single market for goods, so products being moved from Great Britain to Northern Ireland undergo EU import procedures.

It avoids the need for checks on the Irish border, as EU customs rules are enforced at Northern Ireland's ports instead.

Unionists say it damages trade and threatens Northern Ireland's place in the UK.

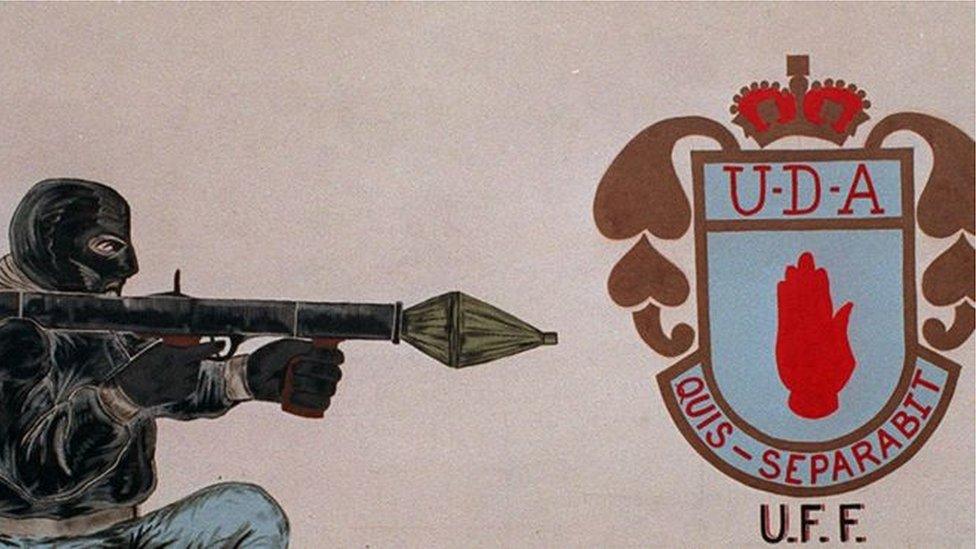

In January, graffiti opposing the Irish Sea border was daubed on walls in some loyalist areas, including parts of Bangor, Belfast, Glengormley, and the home of one of Northern Ireland's main ports, Larne.

These Brexit checks were temporarily suspended amid reported threats against port workers in Larne and Belfast - although the police later said there was no evidence of "credible threats".

In March, a group which includes representatives of loyalist paramilitaries wrote to Prime Minister Boris Johnson to withdraw its support for the Good Friday Agreement, the 1998 deal that effectively ended the Troubles.

The Loyalist Communities Council said it was temporarily withdrawing its backing because of concerns about the protocol.

Lord Frost, the UK Brexit minister, is to meet EU Commission Vice-President Maros Sefcovic in Brussels on Thursday to discuss plans about implementing the protocol.

Read more: What is Brexit doing to Northern Ireland?

Are there other political factors involved?

Some unionist leaders have attributed the violence to the decision not to prosecute leaders of the republican Sinn Féin party for breaching Covid regulations at the funeral of a former IRA intelligence chief last June.

Some 2,000 mourners lined the streets for the funeral of former IRA intelligence chief Bobby Storey in June 2020

Bobby Storey's funeral drew 2,000 mourners - including Deputy First Minister Michelle O'Neill - at a time when strict Covid restrictions were still in place, limiting the number of people who could gather in public.

Many people expressed anger at Ms O'Neill for failing to follow the guidance she insisted the public should follow - guidance which had led to loyalist band parades being cancelled last summer.

Some have accused police of double standards after the Public Prosecution Service (PPS) said there would be no prosecutions - against the police's recommendations.

While DUP leader and First Minister Arlene Foster said she did not share that view, she called on PSNI Chief Constable Simon Byrne to resign.

Mr Byrne said he recognised people were angry, but has refused to step down.

Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis has said the PSNI and the Policing Board need to reconnect with communities to restore trust, adding that the decision not to bring charges over Bobby Storey's funeral had "a very substantial impact" on the street violence.

- Published9 April 2021

- Published2 February 2024

- Published14 May 2024

- Published21 March 2021