Analysis: What is Brexit doing to Northern Ireland?

- Published

The renewed tension in Northern Ireland could have far-reaching implications for the future of the United Kingdom - and post-Brexit relations with the EU.

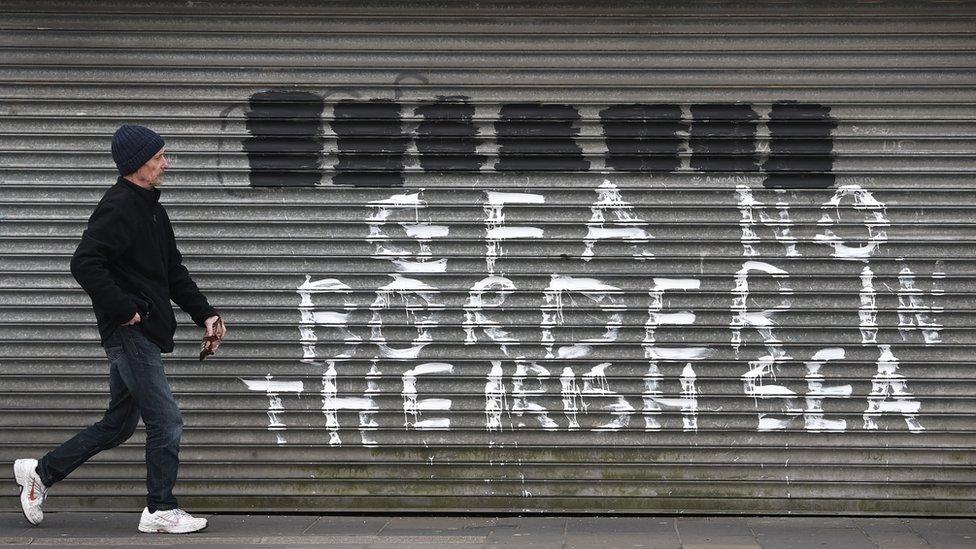

The violence that has erupted this week on the streets of Belfast and other towns and cities in Northern Ireland has many causes.

But anger about post-Brexit trading rules that came into force in February is a factor.

The section of the Brexit deal known as the "protocol" was designed to protect the peace process by avoiding the need for checks on the border with Ireland.

But it also means that some European laws continue to apply in Northern Ireland.

And that has reinforced long-held feelings among Unionists that they are being cut off from the rest of the UK - and that they've been misled by the UK government and that the EU is not listening.

Much of the focus in talks with Brussels on the UK's departure from the EU was on ensuring that trade from Northern Ireland to Great Britain could continue freely - to be "unfettered".

Trading friction

That's what Prime Minister Boris Johnson meant when, in the run up to the 2019 general election, he famously told traders they would have his permission to throw away any new paperwork.

"There will not be checks on goods going from NI to GB," Boris Johnson tells Conservative supporters

It also gave many the impression that trade in the other direction - from Great Britain to Northern Ireland - would be just as smooth. This was despite warnings from the EU, and UK civil servants, that the new rules would inevitably lead to more friction.

The past few months have provided real-world examples as the Protocol kicked in:

Imports of plant and animal products, such as mozzarella cheese, into Northern Ireland from Great Britain now require multiple forms, when previously there were fewer or none

Some firms such as John Lewis suspended delivery of parcels to Northern Ireland, and some packages from Great Britain were labelled as "international", although the department store chain has resumed most deliveries now

Two cigarette manufacturers said they would reduce the range of products, external on sale in Northern Ireland because EU rules on packaging remained

People moving house from Great Britain to Northern Ireland need a customs declaration for their possessions if they use a removals firm

Some of the problems were temporary and have gone away. Others are on the way to being solved with workarounds, or with money or support schemes.

Some have been booted into the long grass, with "grace periods" before the rules are fully applied.

Assembly elections

One European diplomat, who helped to write the Brexit deal, told me it was unlikely that any of these issues had inspired teenagers to throw missiles at the police this week.

Youths clash with police in West Belfast

But each one is a reminder that Northern Ireland is being treated differently from the rest of the UK because of a treaty agreed by the UK government.

And the rhetoric of Unionist politicians suggests it is unlikely that the differences can ever be minimised in a way that satisfies them.

They would prefer the Protocol was suspended - which would be allowed if there was a serious threat to security or the economy - or permanently junked.

That will be the DUP's pitch at the elections for the Northern Ireland assembly next May.

And again when Stormont votes on the continuation of the Protocol in 2024.

Which means the instability around the Brexit deal in Northern Ireland is likely to continue for years.

'Self-fulfilling prophecy'

And it could get even worse. I recently spoke to one of the UK's Brexit negotiators, who asked: How will Northern Irish Leave voters feel if the European Court of Justice is ever asked to rule on how the Protocol is being applied?

British observers also fear that DUP leader Arlene Foster is being forced into increasingly extreme positions - by her own party and by voters demanding an even stronger brand of unionism.

One government advisor also suggested to me that Unionist leaders were whipping up their supporters, risking a "self-fulfilling prophecy" where politicians use inflammatory language, which winds up the public, which then demands an ever-tougher response.

Arlene Foster has called for an end to the violence

That makes it more difficult for the DUP to share power with Sinn Fein, which threatens devolved government and the peace process.

It also makes it harder for the Northern Irish government to build inspection posts at ports and other things it is meant to implement under the terms of the protocol, potentially undermining the Brexit deal itself.

Boris Johnson is also under pressure from some of his own Conservative MPs, who are still pressing for alternative solutions to the Irish border issue, even though these solutions were rejected by the EU many times during the Brexit negotiations.

And what about the EU?

Border poll

The British government accuses them of being deaf to the needs of Unionists and of putting the interests of those who care more about Northern Ireland's relationship with Ireland ahead of those who care about its relationship with Great Britain.

UK ministers say the EU gave Unionists another reason to be upset by almost accidentally suspending the Protocol in January when it was designing a mechanism to screen exports of Coronavirus vaccines.

The EU quickly corrected its mistake and apologised. Officials in Brussels say privately that the problems in Northern Ireland are because the UK was not honest about the changes that were coming and acted too late to minimise their impact.

The biggest question of all is the degree to which the implementation of the Brexit deal affects the number of Northern Irish citizens saying they would like to be part of Ireland.

British law compels the Northern Ireland Secretary to hold a referendum - a border poll - if there is evidence that a majority of the population wants reunification.

Opinion polls suggest a small but growing minority in favour but the law is silent about what evidence should be considered or how a vote would work.

This potential break-up of the UK is why the technical details of the Brexit deal matter to politicians in London, Belfast, Dublin and Brussels.

And to people on the streets in Newtownabbey, Carrickfergus, Ballymena and Londonderry.