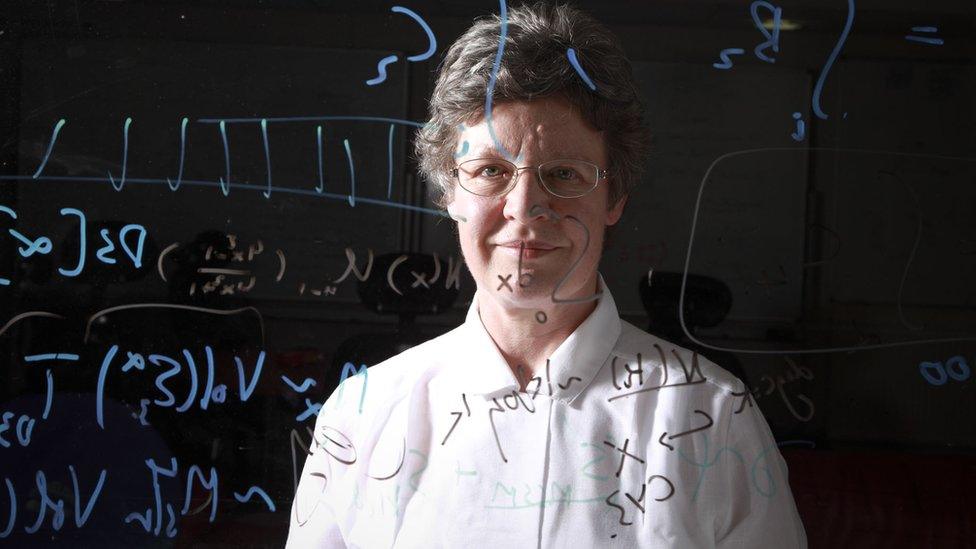

Dame Jocelyn Bell-Burnell: NI scientist awarded Royal Society's highest prize

- Published

A leading astrophysicist from Northern Ireland has been awarded the world's oldest scientific prize for her work on the discovery of pulsars.

Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell is only the second woman to be awarded the Royal Society's highest prize, the Copley Medal.

The medal is awarded for outstanding achievements in scientific research.

In 1967, when she was a 24-year-old student, she was part of a team that discovered the new type of star.

Pulsars are rapidly spinning neutron stars, so named because they appear to pulsate when viewed from Earth.

At the time she was overlooked for a Nobel prize in favour of her male collaborators, although she has argued the prize was awarded appropriately at the time due to her student status.

Dame Jocelyn said she was "delighted" to be the recipient of this year's Copley Medal and said she hoped her presence as a senior woman in science "continues to encourage more women to pursue scientific careers".

"With many more women having successful careers in science, and gaining recognition for their transformational work, I hope there will be many more female Copley winners in the near future," she said.

The Copley Medal predates the Nobel prize by 170 years and was first awarded in 1731.

Notable winners include Benjamin Franklin, Dorothy Hodgkin, Albert Einstein and Charles Darwin.

The medal is accompanied by £25,000 for its recipient, which Dame Jocelyn is donating to a fund providing grants to graduate students from under-represented groups.

'Very much an outsider'

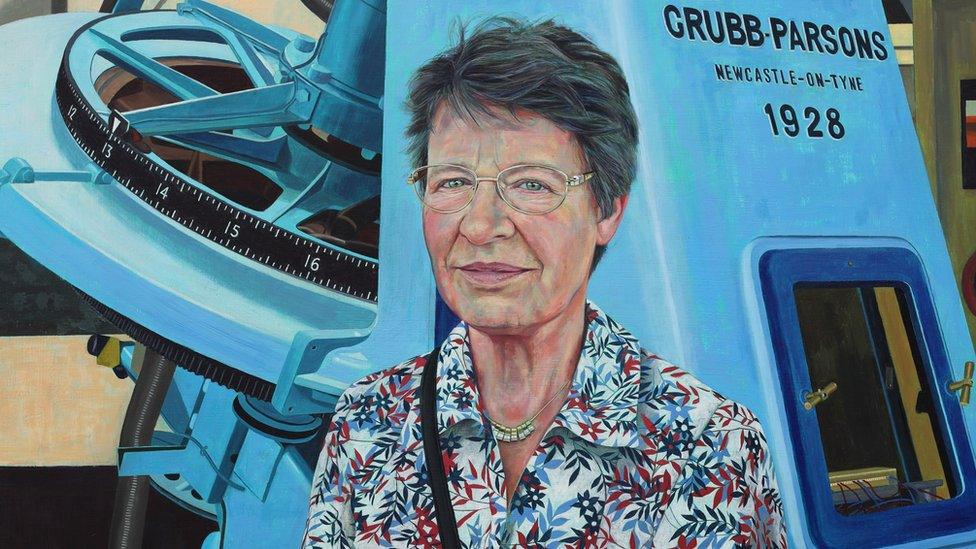

A graduate of the University of Cambridge, Dame Jocelyn was born in Belfast in 1943.

She grew up in Lurgan, County Armagh and attended Lurgan College in the town, before moving to England at the age of 13.

"I reckon that my discovery of the pulsars came about because I was suffering imposter syndrome," she told BBC News NI in 2020.

"I was in Cambridge as a woman from the north and west of the country at the time when most of Cambridge was affluent, south-east England males.

"So I felt very much an outsider - I was quite convinced they were going to throw me out at some point and decided I'd work really hard, until they threw me out, so that I wouldn't have a guilty conscience."

Related topics

- Published28 November 2020

- Published5 February 2014