Holy Cross dispute: The terror and the trauma recalled 20 years on

- Published

Holy Cross: 'I was in the school and we heard an explosion'

Three central figures caught up in the events around Holy Cross Primary School in north Belfast in 2001 have been speaking about the sectarian dispute.

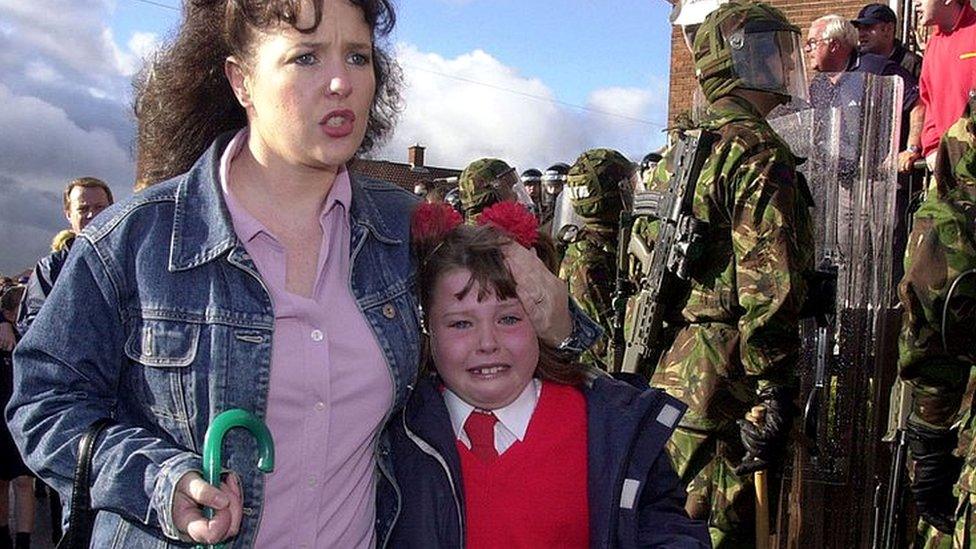

Loyalist protesters tried to block the route taken by the school's pupils and their parents, who were from a Catholic background, on their walk to class.

The then school principal, a Presbyterian minister and a Catholic priest say the scars are still there.

Only now can Fr Gary Donegan even bring himself to speak of the events because it is still so raw.

He was a young priest starting out when it began.

"I had only just arrived - it was actually my birthday when the thing kicked off," he said.

"But by 3 September when the worst part of it was actually taking place I suppose I was really shocked, because to some extent children were sacrosanct and they were right in the midst of this."

Fr Gary Donegan said he had been unable to speak about the events for a long time

Twenty years later, Anne Tanney still wonders if it really happened.

Mrs Tanney, who was the principal of Holy Cross Girls' Primary School at the time, said the worst moment was when a pipe bomb exploded as the children were walking to school through the lines of police officers keeping back the loyalist protestors.

"I was in the school and we heard this explosion outside and we knew the children were coming," she said.

"We ran out down to the gate and I thought there would be a child carried in dead or somebody would be dead, but they were in a terrible state."

Reverend Norman Hamilton said he worried what the exposure was doing to people living in the area

The dispute was worldwide news which worried the Reverend Norman Hamilton, who is now a retired Presbyterian minister.

"I remember, more than once, being quite taken aback at the range of media who were there from Australia, from Canada, from France, even from the Far East," he said.

'Serious psychological damage'

Dr Hamilton said he wondered what it was doing "not just to this community to be exposed on the world stage but what is it doing to Northern Ireland to be exposed like this on the world's stage?"

As for Fr Donegan, he said when the 10th anniversary came around he "deliberately suppressed any kind of marking of it" because it was such a raw experience.

"I think long-term there was serious psychological damage done, " he said.

"I buried a couple of the mothers and, ironically, their children were able to move on but they were not.

"I've been offered book deals. I've been offered all kinds of things, but until now I've said I want to focus on now. You can't forget, we'll never forget what actually happened, but I want to focus on what's actually happening now."

Soldiers at a barrier on the Ardoyne Road during the Holy Cross dispute in Belfast

So 20 years on what is happening now?

"I don't think it will be replicated but I have to say I am a bit troubled in the back of my mind that tensions can arise and go in unexpected directions, not in this area, particularly, but just generally," said Dr Hamilton.

"I think, to be honest, we are in a sort of stalemate because the big political picture works itself out by default at local level, so whilst the communities are at greater ease with each other I'm not sure, in terms of reconciliation, and the building of close, mutually supportive relationships that we have progressed very much.

"The political fracturing is still a real problem. You cannot expect local communities to do what big-picture politicians are either unwilling or unable to do."

Fr Donegan said it was important for people with experience to move in quickly when tensions started to rise.

"I believe if it had happened in one of the leafy suburb schools the unions would have been out, the educationalists would have been out. But it's kind of like: 'It's Ardoyne, it's the Shankill' - you know to some extent we're alright jack sort of," he said.

"I find, sometimes, people who don't have experience, even pastors or priests... a lot of these people wouldn't know an interface if it walked up and shook them by the hand and sometimes they are better actually not being there.

"We won the peace inch by inch and people like Norman and I now are not prepared to let any shrinkage.

"We're prepared to hold on to those inches, so if we see anyone in some way starting to impinge on that, we have a moral obligation and a duty to get in there and actually do something about it."

Anne Tanney said the worst moment was when a pipe bomb exploded as the children were walking to school

Mrs Tanney says the school received cards and calls from people all over the world. She and her husband were even offered a free holiday in New Zealand.

She says it was important to tell the children there were many good people in the outside world who could be trusted.

"It's a terrible thing for a child to grow up thinking that they're in a world they can't trust and where their parents can't help them," she said.

"And it was very bad for parents because they felt they couldn't protect their children and that's the worst thing that can happen to a parent."

Related topics

- Published5 September 2021

- Published1 September 2016

- Published3 September 2011

.jpg)