Forgotten sisters of WB Yeats step out of the shadows

- Published

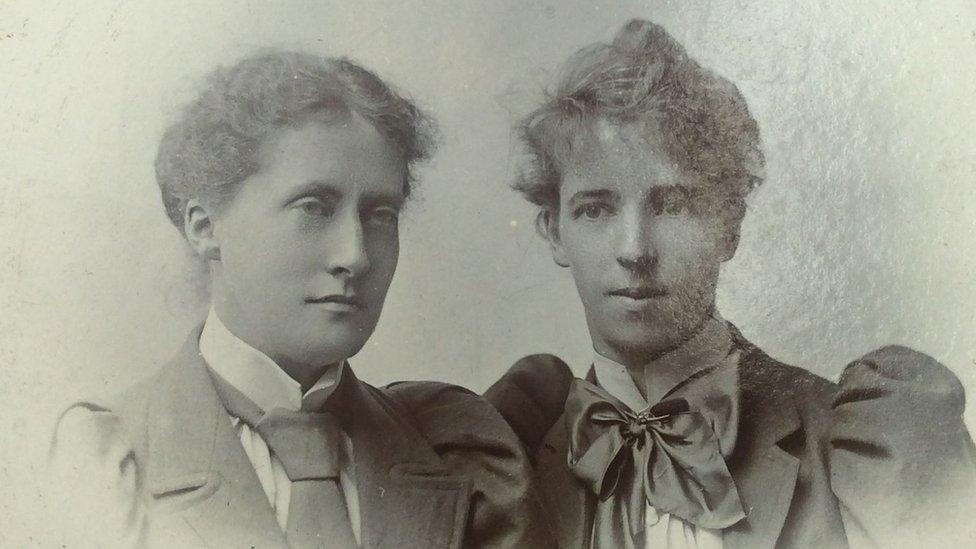

Lily and Elizabeth Yeats helped create a new sense of Irish identity

A blue plaque on a house in Chiswick, London, commemorates three famous men who lived there.

On it are John Butler Yeats, portrait painter, and sons Jack Yeats, the well-known artist, and William Butler Yeats, Nobel prize-winning poet.

But what of their sisters, the forgotten Yeats women?

Sisters Elizabeth and Lily Yeats share a fleeting derogatory reference in James Joyce's Ulysses where they are labelled the "weird sisters".

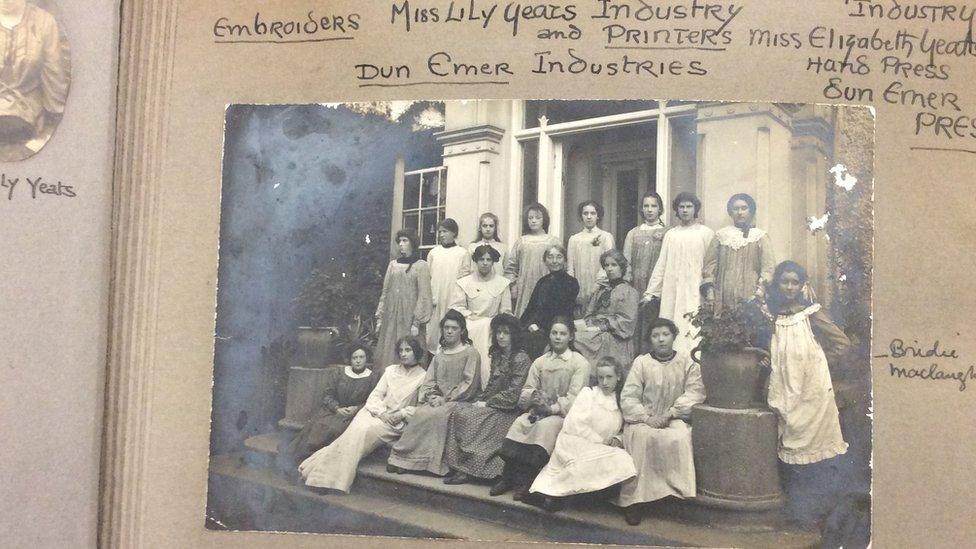

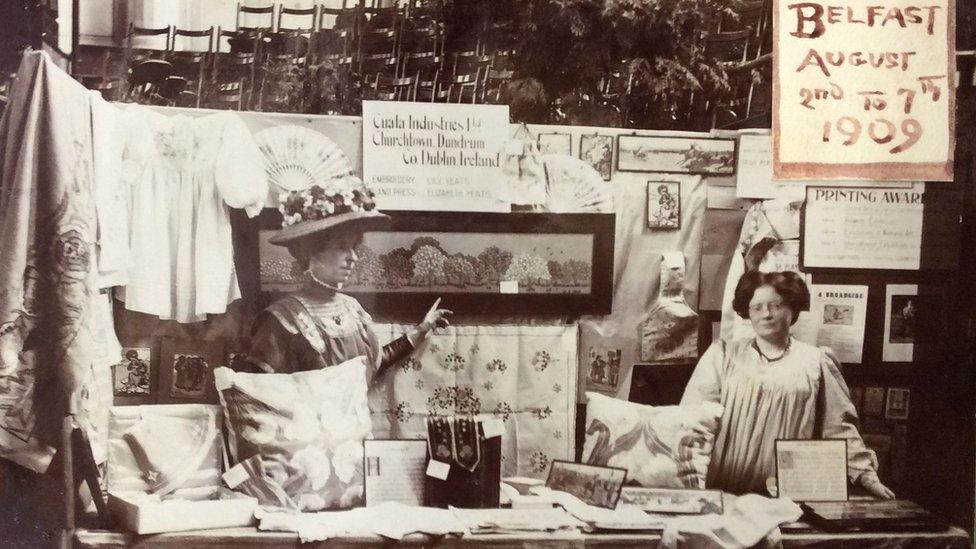

The Yeats sisters and their staff who were all women

Aside from that, their important role in the Celtic revival seems to have been overlooked.

Now an academic project at Trinity College Dublin is bringing the sisters and other Irish women artists back into the spotlight.

The Yeats sisters built careers in their own right and were instrumental in creating a strong sense of Irish identity in the early 1900s.

The Cuala Press Project at Trinity shines a light on the arts and crafts enterprise set up by them in Ireland in 1908.

As the country moved to partition in 1921, Cuala Press presented a fresh image of Ireland across the world. Their handprinted books, cards and prints were popular in Ireland, the UK and America.

Now, for the first time, the Cuala prints are being digitised and offered to a wider audience online.

Dr Angela Griffith from Trinity's History of Art department said the aim is to generate fresh interest on the women artists of the Cuala Press.

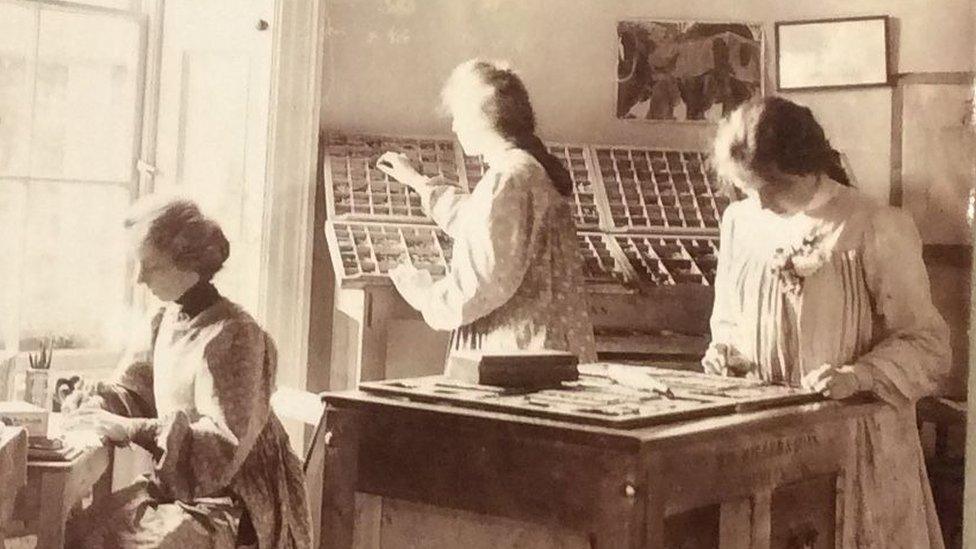

Elizabeth Yeats and two employees in Dublin in 1904

"We believe that the work of Elizabeth Yeats, and the female artists who worked with her, deserves to be re-visited," she said.

"Having public access to this material as a curated collection, allows us to think more about what it was like to live and work as a woman 100 years or more ago during a time of new - and ever-changing - cultural, social, and political landscapes.

"And, as is the role of art, it makes us think and re-evaluate our lives today."

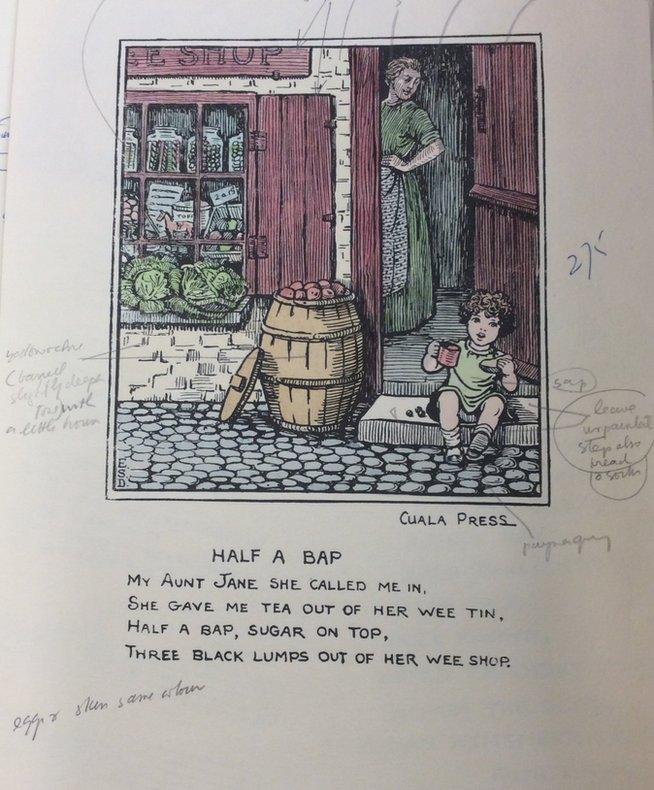

A Cuala Press print of an old Belfast song

At the turn of the last century, Lily Yeats trained in embroidery with William Morris's daughter May at the world famous arts and crafts centre. Elizabeth published books about painting.

They set up Cuala Press, which specialised in embroidery and handprinted books and prints of the Irish literary revival, employed only women - 20 to 30 at any one time.

A Cuala Press print by Belfast sisters Ruth and Emma Duffin

Among those whose work featured were Belfast sisters artist Emma Duffin and writer Ruth Duffin,

"It was an all-Ireland enterprise," said Dr Griffith.

"There was a real connection across the country, arts and designers were supporting each other and that continued even after independence and the setting up of the [Irish] Free State."

As Ireland moved forward politically, the work reflected the sense of a country forging its individual identity.

"It was about giving Irish people a view of themselves set in their own landscape," said Dr Billy Shortall, her colleague on the Cuala Press project at the Irish Art Research Centre.

"Prior to that, a lot of art work was about landlords commissioning landscape paintings of their estates to be hung on the wall.

Elizabeth Yeats, left, at an arts and crafts fair in Belfast

"Clichéd cartoons in newspaper of the time were of the dumbfounded Irish person...that was a common narrative particularly in the British press that fed into the stereotype of British colonial rule - 'We're only colonising these people because they are incapable of self government'.

"The Celtic Irish cultural revival had its roots in literature and art and music and language.

"It gave people a view of themselves that was different to what they had been used to seeing."

Some might argue that the paintings are chocolate boxy or stage Irish.

Some prints appear strikingly odd to the modern eye.

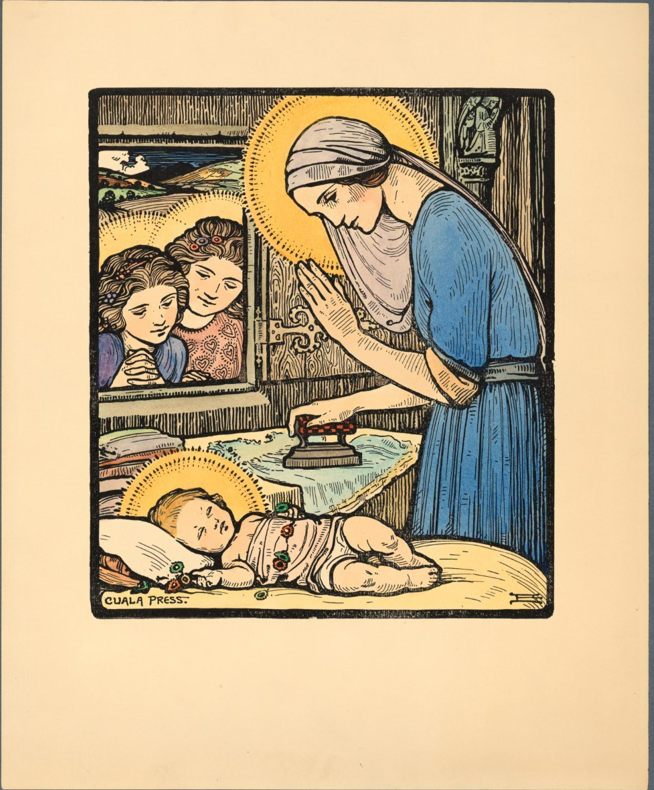

A portrait of the Madonna as an Irishwoman ironing

One shows the Madonna as an Irishwoman ironing as a red-headed baby Jesus lies close by.

But the project leaders argue that they were radical for their time.

"People will be able to look at these images and ask new questions - what do they tell us of the time and what do they tell us about ourselves," said Dr Griffith.

The first images from the archive - donated by the Yeats family and by Vin Ryan from the Schooner Foundation - are already on line, external.

The hope is that galleries and museums will add to the collection, helping to bring the Yeats sisters and women artists who worked alongside them out of obscurity.

Related topics

- Published21 May 2016

- Published20 May 2015

- Published31 January 2015