Good Friday Agreement: NI Executive likened to Starship Enterprise

- Published

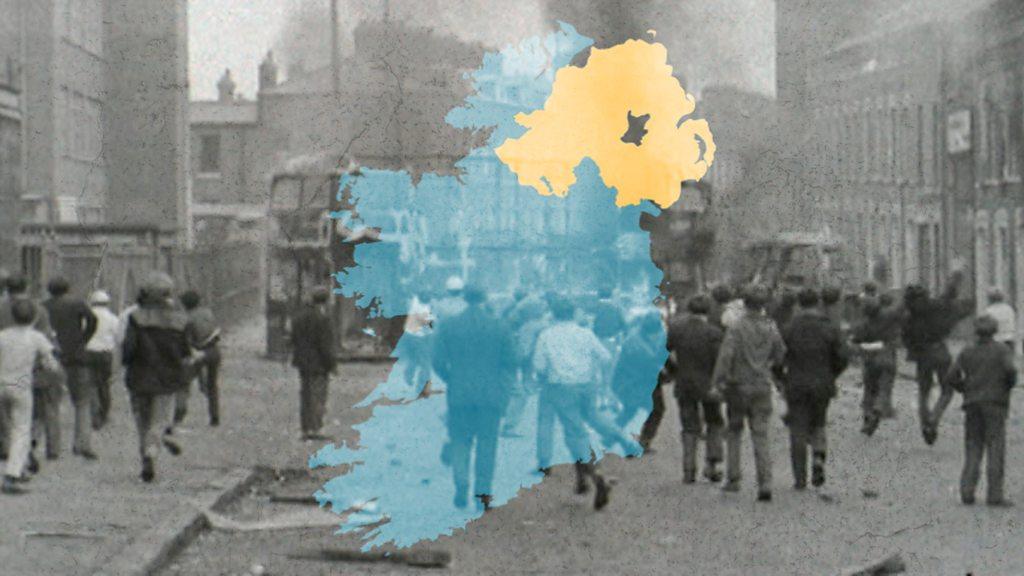

The power-sharing Northern Ireland Assembly was set up as part of the Good Friday Agreement

The Northern Ireland Executive was likened to Star Trek's Starship Enterprise in being "tasked to go where man has not gone before".

This has been revealed in newly-released state papers from 1999.

The NI Civil Service did remove the split infinitive of "to boldly go", replacing it with a more grammatically correct version.

The previously unseen documents detail efforts to create a government following the Good Friday Agreement.

The Northern Ireland Office (NIO) files reflect fears by officials of anti-climax and inertia following the euphoria felt by many after the 1998 referendum.

The majority of files newly released by the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, external (PRONI) relate to 1999, although some cover earlier years.

They are publicly available online on the PRONI website and available to view at PRONI from 10:00 GMT on Thursday.

Then prime minister Tony Blair and taoiseach (Irish PM) Bertie Ahern sign the Good Friday Agreement in 1998

The Good Friday Agreement was signed on 10 April 1998 after intense negotiations between the UK government, the Irish government and Northern Ireland political parties.

Among other things, it set up a power-sharing Northern Ireland Assembly.

From autumn 1998, Northern Ireland civil servants were working to prepare a programme for government in the expectation that a Stormont Executive would be formed in spring 1999.

In the event, an executive was not formed until December 1999.

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) took two ministries, but refused to attend executive meetings in protest at Sinn Féin's participation.

The state papers detail civil servants' concerns about the ability of local politicians to govern Northern Ireland effectively.

'Significant mentality shift'

The burden to establish a programme for government fell largely upon civil servants due to "the absence of any political guidance" and the lack of detail on social and economic issues in political party manifestos for the assembly election held in June 1998.

Officials felt devolution would require a significant mentality shift for the newly elected assembly members (MLAs).

According to one document, having previously been in "permanent opposition mode", MLAs would now have "to confront the hard decisions associated with priority-setting and resource allocation".

"There will be unrealistic expectations about the degree to which an assembly can solve the region's economic and social challenges," another memo said.

In an echo of the stasis at Stormont in 2022, there were also worries in 1999 that mandatory coalition could simply lead to political inertia.

"The executive itself will be an involuntary coalition with internal political tensions that could degenerate into continual attrition between and within unionist and nationalist blocs," was the verdict of one official.

There was also the spectre of continuing violence, despite the agreement and paramilitary ceasefires.

For instance, over nine days between 4 and 12 July 1998, there were 598 attacks - 19 of which involved shooting and 42 were bombing incidents - on security forces, which injured 70 police officers.

Many were related to the continuing standoff over the Drumcree Orange Order parade in Portadown, County Armagh.

The Real IRA detonated a bomb in Omagh town centre in August 1998

These stark statistics were recorded by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and are part of a file on civil unrest in the state papers.

The tension and violence halted abruptly early on Sunday 12 July when news broke of the tragic deaths of the three young Quinn brothers - Jason, Mark and Richard - in a firebomb attack on their home in Ballymoney, County Antrim.

Just over a month later, in August 1998, the Real IRA detonated a bomb in Omagh town centre, external on a busy Saturday afternoon.

Twenty-nine people, including a woman pregnant with twins, died in the bombing which was the biggest loss of civilian life in a single incident in Northern Ireland during the Troubles.

In the aftermath, officials from the Directorate of Health were "at a loss to understand the persistent refusal" of Tyrone County Hospital "to accept outside help given the overwhelming numbers of patients".

These concerns were highlighted in a memorandum written two days afterwards, on 17 August.

"Patients were still being stabilised for transfer late in the evening and fully equipped teams from the Royal, Altnagelvin and Craigavon could have been on site in Omagh much earlier," the memo said.

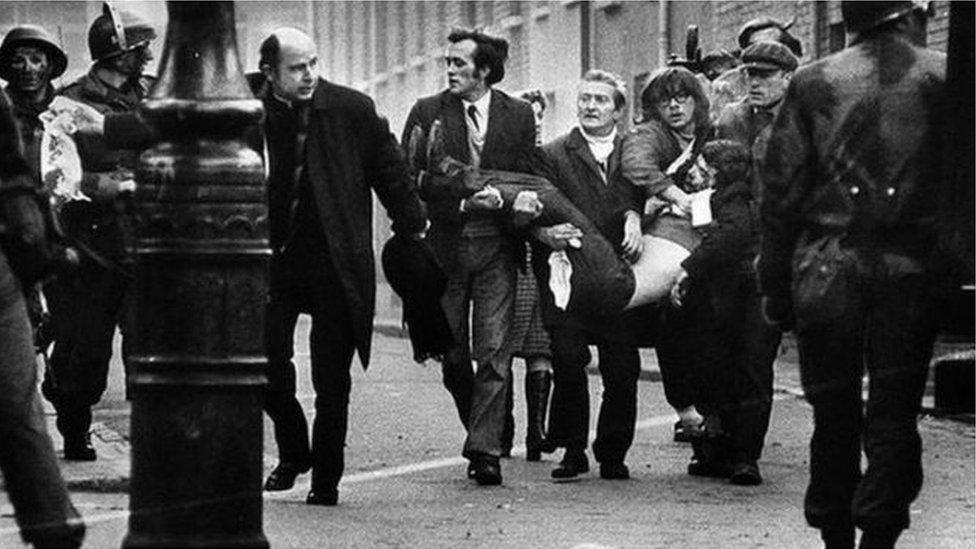

Thirteen people were killed and 15 wounded on Bloody Sunday

A new inquiry into Bloody Sunday was also announced in 1998.

NIO officials recommended an apology, suggesting that "there is a lot to be said for saying sorry".

Northern Ireland Secretary Mo Mowlam resisted pressure from Defence Secretary George Robertson to make the apology the government's last word on the subject, but assured him that "no soldier or other crown servant should be placed in jeopardy of legal action".

Meanwhile, other files detail the UK government's reluctance to liberalise Northern Ireland's abortion laws.

In a survey of Northern Ireland's political parties conducted in 1992, the Communist Party was the only one to favour the full extension of the 1967 Abortion Act to Northern Ireland.

Both the DUP and Social Democratic and Labour Party "were totally opposed" while the Ulster Unionist Party and Alliance did not have a policy as they deemed it a matter of individual conscience.

No MP from Northern Ireland at Westminster had "ever spoken … or made representations in favour of extending the 1967 Abortion Act to Northern Ireland or making the existing laws less restrictive," an NIO paper noted.

By contrast, in December 2022, the current Northern Ireland Secretary Chris Heaton Harris commissioned a permanent abortion service in Northern Ireland.

Related topics

- Published3 April 2023

- Published12 May 2022

- Published13 August 2019

- Published9 April 2018