Brexit: Can better UK-EU relations lead to NI Protocol deal?

- Published

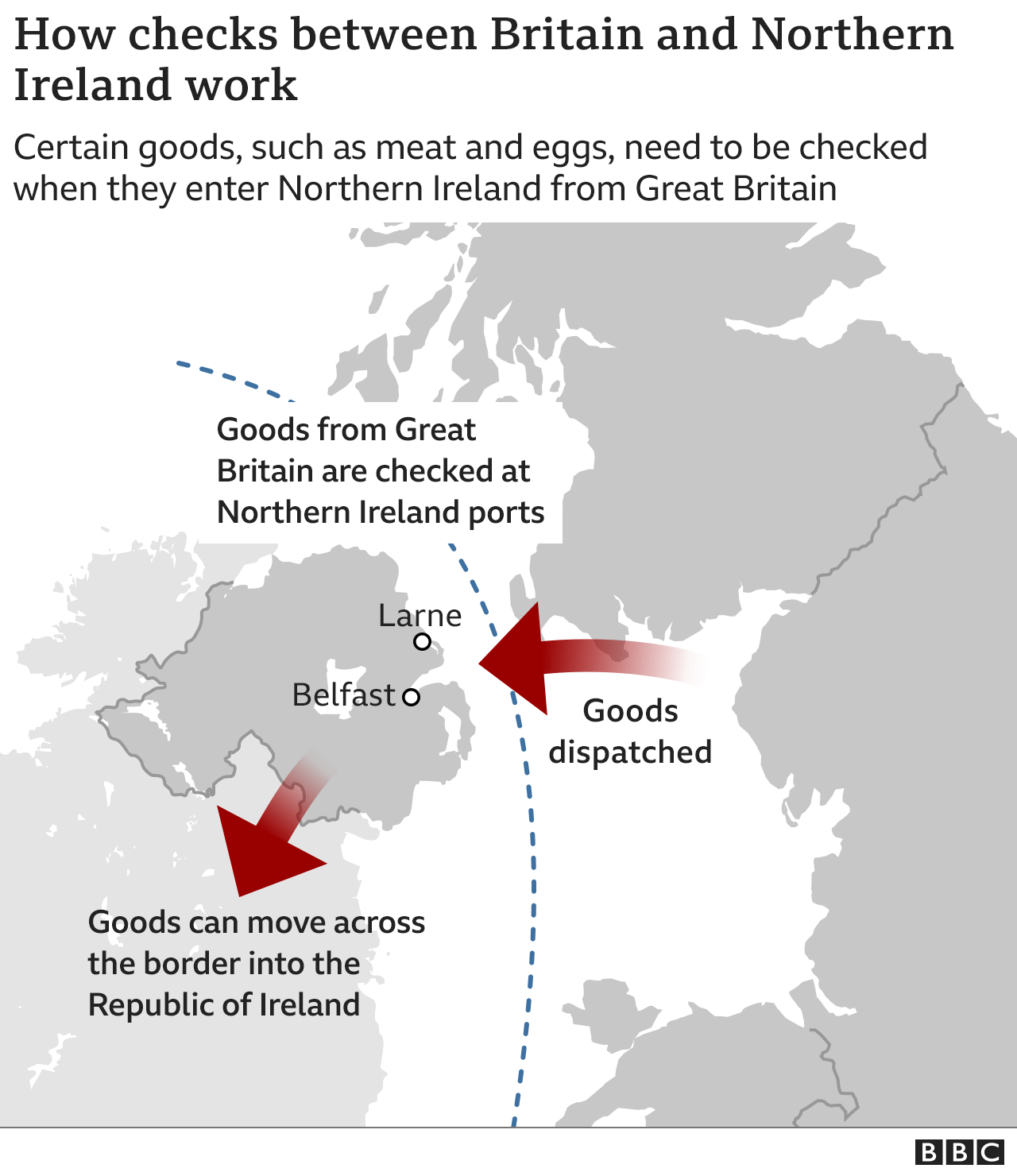

Food products faces the most onerous checks at Northern Ireland's ports

Relations between the UK and the EU improved this week as they reached agreement on sharing trade data.

It could pave the way to a wider deal on the Northern Ireland Protocol and, eventually, the political stalemate at Stormont.

The controversial post-Brexit arrangement was originally agreed by the two sides in 2019.

But there are still big gaps to be breached, as illustrated by just one issue - the trade in food products.

What is the protocol?

The UK and the EU agreed it was neither practical nor desirable to have a post-Brexit trade border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

The protocol keeps Northern Ireland inside the EU's single market for goods, meaning trade can flow across the land border without new paperwork or checks.

The DUP has prevented the formation of a Stormont government in protest over the Northern Ireland Protocol

However, it also means there are new checks and controls on goods entering Northern Ireland from Great Britain.

That has caused difficulties for some businesses and is opposed by unionists in Northern Ireland.

The biggest unionist party, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), is preventing a government from being formed in Northern Ireland as a protest.

The UK and the EU agree that the protocol as it was originally agreed is too difficult in practice.

But they have not been able to agree on what changes should be made.

Where does food come into this?

The EU has strict rules governing the entry of food products into its single market.

The protocol means those rules cover movement of food from Great Britain, where most supermarkets have their distribution centres, to shops in Northern Ireland.

That means that the trade in food faces the most onerous paperwork and checks, even though the protocol has never been fully implemented in that area due to "grace periods".

The EU's rules on food imports are based around export health certificates (EHCs).

Live animals and products of animal origin - meat, milk, fish and eggs - need an EHC to enter the single market.

The EHC has to be signed by a vet or other qualified person in the exporting country after they have inspected the goods.

An EHC is needed for every different product line - for example there are different certificates for milk and yogurt rather than a generic dairy certificate.

Grace period

The grace period means that supermarkets and some other large retailers in Northern Ireland are being allowed to move lorries full of different food products with just one certificate.

The EU's second line of defence for food safety is the operation of border control posts (BCPs).

All goods which require EHCs must pass through those facilities where there are three types of checks - on the documents, verification of the identity of the goods and some physical inspections.

Temporary BCPs are operating at Northern Ireland's ports.

What has the EU proposed?

The EU first made proposals for change in October 2021 and added more detail in June 2022, external.

Its major proposal is that a version of the supermarkets grace period could be made permanent and applied to a wider range of retailers.

The EU's chief negotiator Maros Šefčovic said that lorries entering Northern Ireland from Great Britain would only require a three-page certificate, though separate certification would still be needed for higher-risk goods such as chilled mincemeat.

Foreign Secretary James Cleverly (left) and EU chief negotiator Maros Šefčovič signed an agreement to share trade data

There were conditions attached to this offer: the UK must agree to share real-time data on trade movements from Great Britain to Northern Ireland and must commit to building properly resourced border control posts at Northern Ireland ports.

This week the UK agreed to do both of those things.

So if you are an optimist you could say that that clears the way for the EU to move quickly on this issue.

However there were caveats to the EU offer.

The light touch only applies to products originating from the UK or the EU so, for example, a case of Madagascan prawns coming from a Great Britain supermarket depot would not benefit from reduced checks and paperwork.

Secondly it only applies to retail goods, not ingredients which are intended for further commercial processing.

Third the goods will also have to be labelled for UK sale only, meaning increased cost and complexity for retailers and manufacturers.

Dairy products require export health certificates in order for them to be allowed into Northern Ireland

Possibly some of these EU caveats could be negotiated down.

But there are more fundamental differences.

What does the UK want?

The UK published its plans for fundamental reform of the protocol, external in June 2022.

In terms of the movement of goods the central idea is the concept of green lanes and red lanes for trade.

Great Britain goods moving through Northern Ireland into Ireland or the wider EU would use the red lane and continue to be checked at Northern Ireland ports.

But goods coming from Great Britain into Northern Ireland and which are staying there would use the green lane.

That would include food products.

That means there would be no checks and the paperwork would be minimal.

To qualify for the green lane a businesses would need to be a member of a trusted trader scheme.

There's no guarantee that goodwill will result in a resolution of the protocol conundrum

The government says that new scheme would require firms to provide "detailed information on their operations and supply chains to support robust audit and compliance work".

There is a slight nod to the fact that some food products may need differential treatment with the mention of a "bespoke biosecurity assurance framework" that would manage arrangements for goods that "pose a different order of risk".

Light touch

But that sort of light-touch risk management is a world away from what the EU is talking about with continuing certification and checks.

So for a deal in this area either the UK would either have to water down the green lane concept or the EU would have to demonstrate a hitherto unseen appetite for increased risk.

Or perhaps there is a third way the negotiators can find.

But that illustrates that even with goodwill and a joint desire to solve problems it will take time to reach a deal and success is not assured.

Related topics

- Published2 February 2024

- Published14 December 2022