NI Election: Everything you need to know about the 2017 vote

- Published

Parliament Buildings at Stormont - will it host an NI government after March?

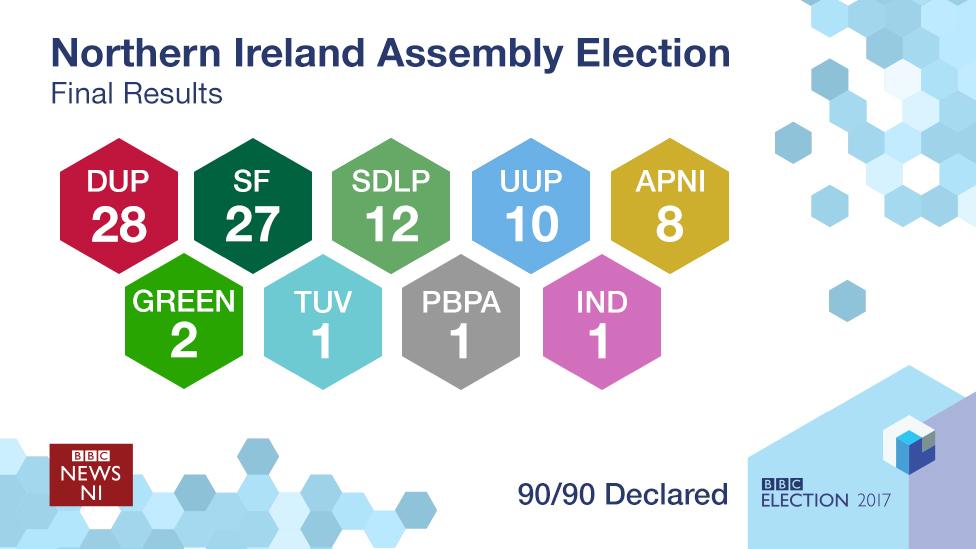

The results are in - Northern Ireland went to the polls on 2 March to elect a new government.

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) retained its position as Northern Ireland's largest party but won only one seat more than Sinn Féin, which was the big winner of the day.

But why did Northern Ireland come out for an election in the first place? Here's a guide to the circumstances that led up to the 2017 vote.

Wasn't there an election in Northern Ireland very recently?

That's right, Northern Ireland already did the election dance last May but we're going back to the ballot box just 10 months later.

So what happened?

Stormont's power-sharing government collapsed in January.

The collapse came about after Northern Ireland's deputy first minister, Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness, resigned.

In Northern Ireland, the government must be run by Irish nationalists and unionists together.

The system was set up by the Good Friday Agreement following years of conflict. A first and deputy first minister, taken from the largest and second largest parties elected, are appointed to lead an executive of ministers.

Although they have different titles, they essentially have equal authority and, in theory, work together in partnership.

Martin McGuinness resigned in January after Sinn Féin falling out with the DUP led by Arlene Foster

At the beginning of the year, the first minister was Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) leader Arlene Foster who worked with Mr McGuinness as deputy first minister.

But after he resigned, and Sinn Féin refused to nominate a replacement, Secretary of State James Brokenshire had no choice but to call for a new election.

Why did Martin McGuinness resign?

He stepped down after a row between Sinn Féin and the DUP over a green energy scheme scandal - the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI).

You can read all about the scheme here. But, here's the short(-ish) version:

Mrs Foster was in charge of the scheme when it was set up in 2012. It was designed to encourage businesses to switch from fossil fuels to environmentally friendly alternatives.

But, subsidies were over-generous and initially there was no cap on payments - leading to what has been dubbed the "cash-for-ash" scandal.

The scheme is projected to run £490m over budget, although a plan to eliminate the overspend was passed by the assembly just before it broke up in January.

Sinn Féin asked that Mrs Foster temporarily stand aside while an investigation was carried out, but she refused.

So the resignation was just over this scandal?

It's more complicated than that.

While the scheme was the catalyst for Mr McGuinness resignation, he and Sinn Féin have said it was just one of many issues it had with the DUP, including Brexit (which the DUP backed, while Sinn Féin did not), same-sex marriage (to which the DUP is opposed, while Sinn Féin is in favour) and a potential Irish language act.

These issues could become very important if the two parties retain their dominant positions as deal makers in March.

OK, so what's new this time?

Well, for one, Martin McGuinness is not back for re-election. A week after resigning, he announced he was quitting frontline politics because of ill health.

Michelle O'Neill became Sinn Féin's Northern leader after Martin McGuinness' resignation

Michelle O'Neill was appointed Sinn Féin's Northern leader in his stead and is leading the party into an election for the first time.

Other than that, there's a major change in numbers, as less people are going to get elected to the Northern Ireland Assembly - only 90 MLAs (Members of the Legislative Assembly) as opposed to 108 last year.

Why the reduction?

To reduce costs, Stormont decided in February 2016 it would cut the numbers.

However, the law is being implemented a bit sooner than expected - it was thought the reduction would be introduced for the next scheduled election in 2021.

Now, 18 MLAs will lose out less than a year after getting in the Stormont door.

How might that affect the results?

It remains to be seen, but the big two - DUP and Sinn Féin - are still the parties to beat. They led the power-sharing government after 2016's election and have been the big players at Stormont since 2007.

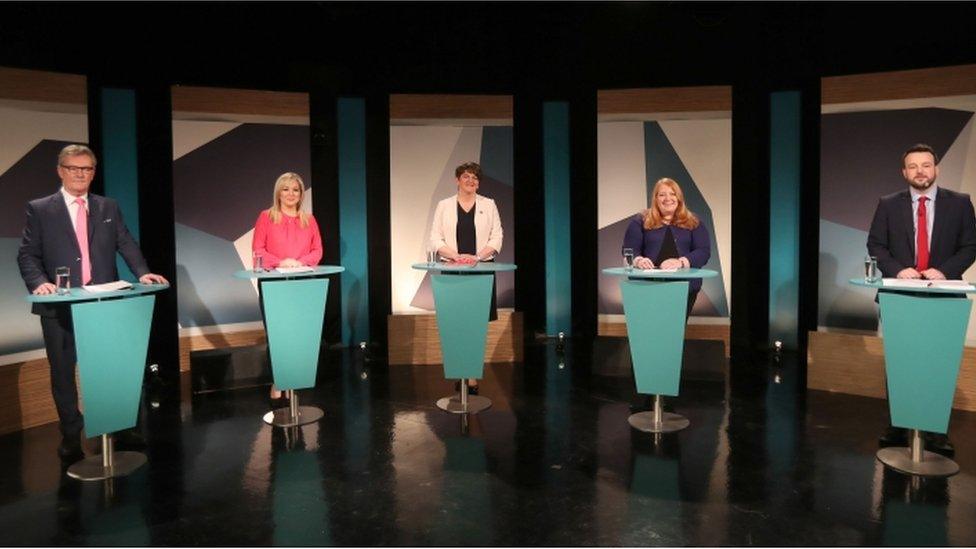

The leaders of Northern Ireland's main parties (from left to right): Mike Nesbitt, UUP; Michelle O'Neill, Sinn Féin; Arlene Foster, DUP; Naomi Long, Alliance; Colum Eastwood, SDLP.

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) and Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), the two other major unionist and nationalist parties, are aiming to usurp them.

Last year, these two formed the first official opposition at the Northern Ireland Assembly.

Meanwhile the Alliance Party, Northern Ireland's fifth largest with eight MLAs elected last year, is a centrist, non-sectarian group that straddles the line between unionist and nationalist.

They are hoping to take advantage of any voter dissatisfaction at the DUP/Sinn Féin leadership and are also under new leadership, with former MP Naomi Long at the helm.

What about smaller parties and independents?

They've been bubbling up in recent years. Jim Allister, leader of hard-line unionist party the TUV (Traditional Unionist Voice) has been a fixture at Stormont since 2011, which will be hoping to add to its solitary MLA.

Likewise, the Green Party doubled its representation to two MLAs in 2016 and is optimistic of a strong showing.

Also look out for anti-austerity outfit People Before Profit, who took their first two seats ever last year and are running even more candidates this time around.

How will the election work?

A form of proportional representation called Single Transferable Vote (STV) is used to elect candidates to the Northern Ireland Assembly.

Voters rank candidates in order of preference.

Candidates are then elected according to the share of the vote they receive. You can read an in-depth guide to the system here, or check out this video explainer.

How does the STV system work to elect MLAs in Northern Ireland?

OK, so that's the state of play. But what will happen after the election?

The two biggest unionist and nationalist parties will get together and try to form a new government.

If it's the UUP and SDLP, then we should see a Stormont government under new leadership in reasonably short order.

But, it's more likely that once again the DUP and Sinn Féin will be tasked with reaching agreement. And since they spectacularly fell out just a few weeks ago, that could be a challenge...

So they won't be able to form a government?

That remains to be seen.

But, Sinn Féin has repeatedly said there will be "no return to the status quo", so it appears they will not re-enter government with the DUP without agreement over thorny issues like the failed RHI scheme and the Irish language.

Irish foreign minister Charlie Flanagan and Secretary of State James Brokenshire could play major roles if an NI Assembly cannot be formed

It's apparent that some in-depth negotiations will be needed if both parties are elected.

But the clock will be ticking - those tasked with forming a government have three weeks to agree and appoint an executive of ministers.

If they can't find agreement on those issues then, technically, there could be another election.

Another election - really?

It's pretty unlikely. Instead, some other way of governing Northern Ireland will have to be found with direct rule from Westminster a real possibility.

Nationalists have said that direct rule would be unacceptable, and called for the British and Irish governments to come together to form some kind of "joint authority" if the Northern Ireland Assembly cannot be re-established.

However, unionists are against this idea while the Secretary of State James Brokenshire has said he is not considering any alternatives to a Northern Ireland Assembly.

Whatever happens in Thursday's election, it's likely to be just the start of Northern Ireland's journey back to devolved government.

- Published23 February 2017

- Published16 January 2017