Stormont: Criticism as assembly stalled two years on

- Published

- comments

The Empire comedy club showcased plenty of jibes about Stormont's politicians

In a bar in Belfast on a cold evening in January, it's the first comedy club of the year.

Just minutes in, and there's a wisecrack about Stormont's politicians.

The host Andrew Ryan asks an audience member who studies politics: "You're studying politics here? You haven't had a government for two years, how's that politics working out for you?"

The collapse of Stormont and subsequent limbo has provided a wealth of material for comedians.

But after a snap election that pushed the parties further apart, failed talks after talks and almost two years of scarce decision making, is the joke on us?

Several people in the audience tell me the ongoing lack of government is anything but a laughing matter.

Why did Stormont collapse in the first place?

Watch Martin McGuinness' resignation statement in full

For almost 10 years, the DUP and Sinn Féin worked together in government under a system of mandatory coalition, where unionist and nationalist parties shared power.

But in late 2016, a row developed over the DUP's handling of a flawed green energy scheme that could cost the taxpayer £490m: the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme.

On 9 January 2017, Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness resigned as deputy first minister, citing the DUP's conduct around RHI as the main reason.

That meant DUP leader Arlene Foster lost her job as first minister and triggered the collapse of the Northern Ireland Assembly.

What happened next?

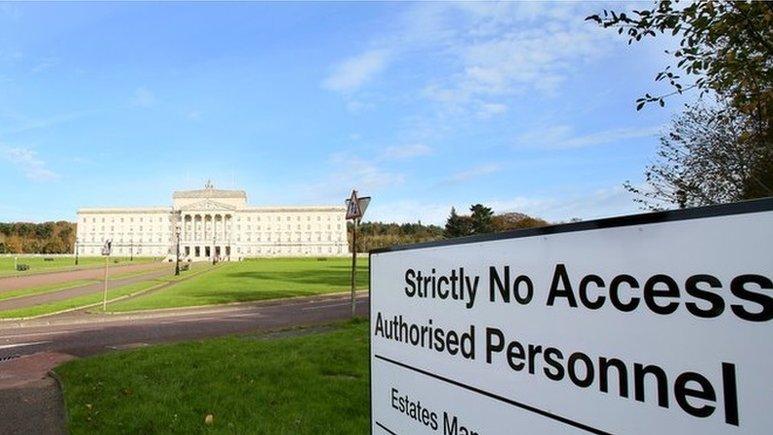

Stormont has been in deep freeze since the political institutions collapsed in 2017

After power sharing collapsed, then Northern Ireland Secretary James Brokenshire had to call a snap assembly election for 2 March 2017.

The DUP and Sinn Féin were still returned as the two largest parties, but this time unionists had lost their overall majority in the assembly for the first time.

All MLAs, new and returning, briefly attended the assembly chamber to pay tribute to Martin McGuinness when he died later that month.

A talks process to try and enable a breakthrough began, but to no avail.

There were several sticking points, but the main one has been Sinn Féin's call for a stand alone Irish language act, which it says would enshrine the rights of Irish speakers in Northern Ireland.

But the DUP has always refused to budge on it, and in February 2018, when it looked like a deal was possible and Prime Minister Theresa May flew to Belfast, talks collapsed at the eleventh hour because of disagreement over the Irish language.

Since then, Stormont has pretty much been in deep freeze, with no sign of thawing out.

Why does it matter?

Because of the impact it has had on day-to-day governance.

In the two years since Martin McGuinness resigned, there has been what Stormont officials describe as a "slow decay" across public services.

Important decisions across all areas - health service, infrastructure, schools - have been effectively put on hold because there are no ministers in place to take them.

There have been calls for direct rule from Westminster to be brought in again, but the British government has been unwilling to take that action.

Instead, it passed legislation last year to give Stormont's unelected civil servants more legal clarity to make decisions in the absence of ministers, until the parties can reach agreement.

What's happening at the moment?

Karen Bradley says she remains optimistic that future negotiations will lead to a breakthrough, but the parties are currently not engaged in a talks process

Not very much.

The parties met the current Northern Ireland Secretary Karen Bradley at Stormont last November to discuss the possibility of kick starting talks in 2019, but nothing has been set up.

With the UK's departure from the EU moving closer, all the parties here and the British and Irish governments have been focusing their efforts on Brexit.

Stormont's 90 MLAs are still doing constituency work, and many of them have been at pains to emphasise their desire to get back to work in the assembly.

In the absence of a deal, MLAs faced a pay cut of 15% last November, with an extra cut of £6,187 this month, which sees their salaries reduced from £49,500 to £35,888.

But even with the reduction in salaries, it seems unlikely that much will rally politicians back to the table to sign an agreement right now.

What has the reaction been?

Dylan Quinn was joined by supporters for parts of the 90-mile route

All comedy aside, the lack of government has caused anger and disillusionment from many at the state of Northern Ireland politics.

At the weekend, a man from County Fermanagh protested against the lack of devolved government in Northern Ireland by walking 90 miles (145km) from Enniskillen to Stormont.

But do all roads now lead to the death of devolution?

Not necessarily, says former Assembly Speaker Eileen Bell.

"Whether they'll have a 'road to Damascus' moment I don't know, but they have to start thinking about the situation here in Northern Ireland," she said.

"We can't go on like this, we don't deserve it, and I would ask them from the bottom of my heart, please try and get government back."

Three former assembly Speakers told BBC News NI what they make of the Stormont stalemate

MLAs maintain that they want to get back to the hill full-time, but neither of the big parties appear willing to budge from their respective corners.

But two other ex-Speakers, Sinn Féin's Mitchel McLaughlin and the DUP's Lord Hay, are at least agreed on one thing: trust is missing from politics right now.

"Martin McGuinness was a problem solver, and I think that kind of leadership is needed again," said Mr McLaughlin.

"People, if given the opportunity, will demonstrate that leadership. If the government in Westminster is preoccupied with Brexit and they send over secretaries of state who can't tie their laces, who aren't allowed to tie their laces, then obviously they're contributing to the impasse."

While Lord Hay recalled his own experience of tough times.

"I remember saying to politicians when I took the Speaker role in 2013: 'Let us work to get through a full term of this assembly for the first time ever'," he said.

"And we did that. It was sometimes a difficult day each day, but you have to work through the system that you have."

The question now, is how many more days will it take before the restoration of that system is seen once again.

- Published7 August 2019

- Published24 August 2018

- Published9 August 2018