Analysis: Could Europe stop Abu Qatada's deportation?

- Published

- comments

Could the European Court of Human Rights stop Abu Qatada's deportation? What would be the consequences if he were removed from the UK?

Abu Qatada, the preacher the government wants to deport, is settling into life on bail after being released from jail.

The European Court of Human Rights says he cannot be deported - and ministers are frantically trying to strike a deal with Jordan to reverse that ruling.

But can't they just deport him anyway? The UK's own highest judges have already approved the move - what could Europe do to stop it happening?

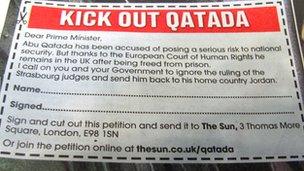

Sun campaign: Petition to ignore the European Court

Backbench MPs are lobbying ministers and The Sun has breezily joined the fray with its own KICK OUT QATADA petition.

Dame Pauline Neville-Jones, a former home office security minister, told the BBC on Tuesday that she believed London could get a new agreement. But she added that if ministers can't reach a deal with Jordan, they shouldn't rule out deportation anyway.

"I would want to know the circumstances; I would not want to land this country in an even more difficult situation," she said. "I don't suppose that would even be my first move. But I would not rule it out over the long term."

So can the government simply ignore the European Court?

Abu Qatada has the protection of an "interim measure" at the European Court. This says he should not be deported until the court's judgement becomes final.

The January judgement barring deportation won't become final until April - and if either the cleric or the government asks the court's Grand Chamber to intervene, the case could drag on for another year.

Ministers across Europe are trying to ignore European Court rulings. This typically happens when governments believe the Court has over-reached itself - just look at the row over whether prisoners should be allowed to vote.

Abu Qatada leaving prison on Monday

But there is a recent case where the British government not only ignored the court - but did the complete opposite.

War crime suspects

In late 2008, during the dying hours of the British military mandate in Iraq, the Army was holding two men accused of a war crime.

It wanted to hand them over to the Iraqi authorities - but the Ministry of Defence had not obtained an assurance that the pair would not face the death penalty.

The European Court granted an interim order banning the UK from transferring the men to the Iraqi authorities. As the mandate ticked away, British officials felt they had no choice but to transfer the men to a Baghdad jail, sparking fury back at Strasbourg.

So what happened? European judges couldn't charge British officials with any crime. So the UK got a snotty letter and a €40,000 fine, external.

The men, by the way, were eventually acquitted. But particular affair was, to put it mildly, an incredibly complex and messy situation. As the cliché goes, hard cases make bad law.

So let's look at what happened to Italy when it deported three terrorism suspects in cases that echo Abu Qatada.

Baroness Neville Jones: There's a long-term risk if no agreement is reached with the Jordanian government

Each man had the protection of the European Court. But Italy ignored that and booted them out. What were the consequences?

European judges didn't call Interpol. There were more angry letters and fines totalling €60,000.

There is a theoretical risk that if the UK ignored the court that it could be kicked out of the Council of Europe, the international human rights club. But ask any international lawyer how likely that is and they'll chortle away to themselves at the stupidity of the question.

So, if the government put Abu Qatada on a plane tonight, the short-term practical effect would be negligible - unless, of course, you are Abu Qatada. But what about the long-term effect?

'Reputational cost'

When Mr Justice Mitting bailed Abu Qatada, external, he said that if ministers failed to overturn the judgement barring deportation, the legal game was up. He added: "Unless the United Kingdom Government is prepared to accept the political and reputational cost of defying a judgment of the Strasbourg Court, deportation would not be possible."

And it is this reputational cost that is the real concern of top lawyers and diplomats who fly the Union Flag overseas.

The UK played a critical role in creating the European Convention of Human Rights because it wanted to replace dictators with the rule of law. Decades on, the Foreign Office projects a message globally - that the UK is a leading advocate of human rights, fairness and good governance.

So, if the UK turned its back on the European Court and deported Abu Qatada, opponents of such a move argue that Britain would in fact be turning its back on its own history. And that, they say, would make it twice as hard for our people around the world to tell other people to clean up their act.

There's one final point. If Abu Qatada were deported while the European Court's bar was in place, it's entirely possible that his lawyers could ask a judge to order that he be returned to London. It's happened before - most recently last December , external- and it could happen again.

- Published15 February 2012

- Published13 February 2012

- Published14 February 2012