Is Brighton the next Maastricht?

- Published

- comments

Brighton is to host a major European summit. But what sort of change does such a large event bring to a city, town, or even a village?

Where is Schengen? OK, Maastricht? Er, Bretton Woods, anyone?

It's a fair bet that most people in the UK have no idea.

But, if only for a few days, statesmen have gathered in these otherwise internationally obscure locations where treaties were signed and agreements reached, changing hundreds of millions of lives.

Schengen, a village in Luxembourg, was where European leaders decided to end the need for passports to travel around much of the continent.

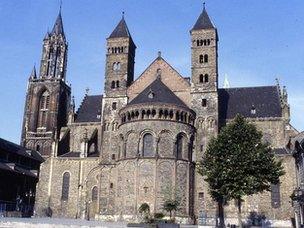

Maastricht, a city in the the Netherlands, was the birthplace of the euro and the modern European Union.

And Bretton Woods, a hamlet in the north-eastern United States, was where the rulers of the world's economies set up the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

'Global stage'

Next month it is the turn of Brighton, an established seaside resort on the south coast of England, to host such a gathering.

The Council of Europe will decide whether to accept a substantial rewriting of the European Convention on Human Rights to allow national courts more powers.

The people of Schengen are very proud of their place in European history

If so, the "Brighton Declaration" will enter the history books.

The resort is used to hosting domestic political conferences, but the city's Green Party-run council is expecting great things.

The cabinet member for tourism, Geoffrey Bowden, told the BBC: "It does put things on to a sort of global stage, or at least a European one.

"It will certainly raise our profile among the people with spending power."

Five hundred delegates from the Council of Europe's 47 member states are expected to attend the conference.

Mr Bowden predicts more people will be encouraged to visit the city of Brighton and Hove in the longer term.

Maybe it will become a shrine for Eurosceptics.

'Sense of freedom'

Large cities like Rome, Paris and Lisbon have little need of a profile boost of the type accorded by the Brighton event.

But what effect have previous conferences, congresses and summits had on smaller venues?

Schengen is a village in Moselle valley of south-eastern Luxembourg, near the borders with Germany and France.

Wine tasting and sightseeing give the area a tourist industry.

The Bretton Woods conference is credited with keeping the town going in difficult times

But the Schengen Agreement of 1985, when French President Francois Mitterrand and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl were among those who took part in a signing on board a pleasure boat, gave it a whole new level of exposure.

It is the reason why millions of Europeans now travel without passports.

Serge Moes, who runs the Luxembourg government's tourist office in London, said: "It's true that, if you ask in the Far East, more people know the name of Schengen than Luxembourg because of the documents they have to complete to come to Europe.

"There's no doubt the village has become associated with a sense of freedom for tourists and others."

The people of Schengen have built a museum to commemorate the signing and a former monastery has become a hotel, a sign of some rise in popularity.

But the Schengen Agreement is controversial, with French President Nicolas Sarkozy threatening to withdraw unless other countries do more to prevent illegal immigration from beyond the EU.

And the location of the village would remain a tough pub quiz question to this day.

Mr Moes said: "At a press conference a couple of years after the agreement was signed, Mitterrand was taken aback when he was asked where Schengen was."

The president - to the disgust of many in Luxembourg - recalled that it was a "charming little village in the Netherlands".

'Integral'

Somewhere at least as mountainous as Luxembourg - and far more so than the Netherlands - is Bretton Woods, a small town in New Hampshire.

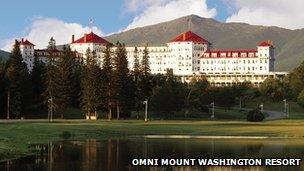

The summit at the grandiose Omni Mount Washington Resort, in the summer of 1944, dealt with planning how to rebuild the global economy when World War II ended.

Attendees included the British economist John Maynard Keynes and US Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau.

The result - the "Bretton Woods system" - included setting up the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Craig Clemmer, the resort's director of marketing, said: "The US government actually came in and injected a significant amount of capital to regenerate the hotel for the conference itself.

"We feel the benefit of this to this day. A lot of financial groups come here for events. Gordon Brown attended a conference last year."

The resort was chosen partly because 35 trains a day but just one main road went there, making it an easy venue to secure.

Mount Washington was once one of more than 20 "grand hotels" in New Hampshire. These were the venues where wealthy men sent their wives and children to stay during the long, hot summers of eastern US cities.

Keynes himself is reported to have been grateful that he could go to Bretton Woods to escape Washington in July.

This season-long trade is less common now, but the 1944 conference still holds an allure.

Mr Clemmer said: "A significant amount of European tourists come here for that reason.

"Probably in the United States, some of the significance is lost on the local population. But the Bretton Woods agreement was vital to the reconstruction of Europe after World War II and many people remember that.

Maastricht is a popular shopping destination for Belgians and Germans

"We do tours every day at 10 o'clock and three o'clock. A significant proportion of this is taken up by the Bretton Woods conference. It's an absolutely integral part of our history."

Maastricht, a small city in the southern Netherlands, is synonymous with the European Union, both to its supporters and critics.

It was the scene in February 1992 for the signing of the treaty which created the EU, increasing its powers from those of its predecessor, the European Community.

It also brought in the European single currency.

Jean Bruijnzeels, an international accounts manager for Maastricht city council, says the event changed the place.

He said: "Everything is far more international than it was before. All the free publicity we gained helped to attract international institutes and firms here.

"About 25% of our population are foreigners, which is a lot for a relatively small city."

'Where's the museum?'

Perhaps the biggest tourist crowd is the shoppers attracted to the ancient city from Germany and Belgium.

But Mr Bruijnzeels said: "The treaty's played a very important role in our external profile. The university, which was established in the 1970s, is popular with overseas students, including many from the UK."

There is "a very small monument" to the treaty signing, Mr Bruijnzeels said, adding: "People sometimes come looking for the 'euro museum', but there is no euro museum. We are planning a more permanent exhibition around the euro and the treaty.

"However, a lot of the media, if they want to cover the euro crisis, come to Maastricht. But they leave disappointed because there's not a real crisis here."

There is, however, a very real wider euro crisis born of the debts racked up by Greece and other countries.

As European leaders work towards a way of resolving matters, the name of Maastricht is as controversial as ever.

The city's university held an academic conference on European issues in February - but no extravaganza, complete with fireworks and carnivals, is planned.

Mr Bruijnzeels said: "These are interesting times to look at the euro. To hold huge festivities at the moment might not be justified."

Brighton, famed for its bohemian and bacchanalian excesses as much as its piers and Royal Pavilion, is also planning a rather sombre and intellectual commemoration.

The most famous constitutional document in British history, the Magna Carta, will also go on display there for the duration of the conference.

But the hoteliers, bar owners and restaurateurs could be celebrating for far longer.

- Published29 February 2012

- Published24 April 2016

- Published8 December 2011