Profile: UKIP leader Nigel Farage

- Published

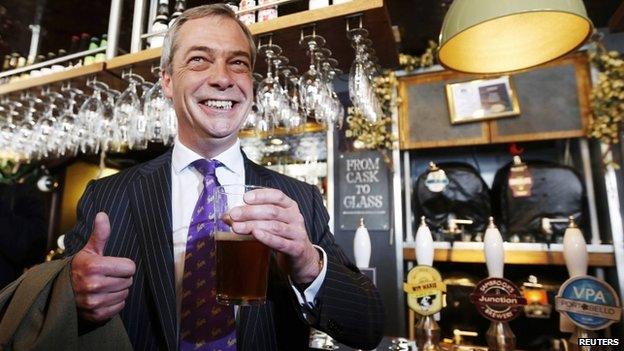

Nigel Farage revels in being "the man in the pub", the political outsider who, to adopt an old beer-advertising slogan, "reaches the parts other politicians cannot reach".

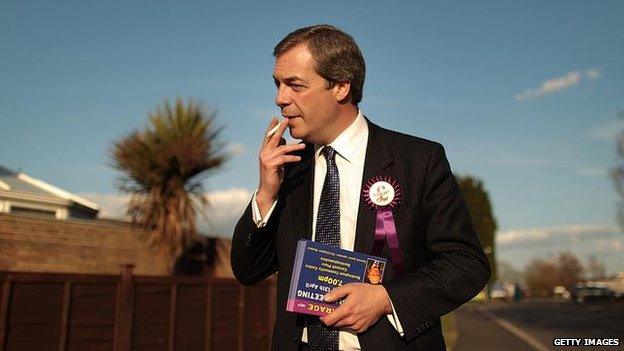

Pint or cigarette (sometimes both) in hand, the UK Independence Party leader attacks today's politicians for being mechanical and overly on-message.

Like regulars throughout the nation's boozers, he states his opinions without much recourse to political correctness.

He inspires affection and respect among those who agree with him on cutting immigration and leaving the European Union.

But, true to his image as an outspoken saloon bar philosopher, he gets into plenty of fights.

Rift with Tories

The latest - a televised debate with Deputy Prime Minister and Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg - was not of his making. Mr Clegg, positioning himself as the spiritual head of Britain's Europhiles, dared Mr Farage to slug things out. He accepted, gladly.

As UKIP regularly out-polls the Lib Dems and continues to record strong showings in Westminster by-elections, he is keen to go further. He wants to win the most UK seats in May's European elections and then go on to gain the party's first MPs at Westminster at the 2015 general election.

These ambitions show UKIP has come a long way under Mr Farage.

But what is his story?

Nigel Paul Farage was born on 3 April 1964 in Kent. His stockbroker father, Guy Oscar Justus Farage, an alcoholic, walked out on the family when Nigel was five-years-old.

Yet this seemed to do little to damage his conventional upper-middle-class upbringing. Nigel attended fee-paying Dulwich College, where he developed a love of cricket, rugby and political debate.

He decided at the age of 18 not to go to university, entering the City instead.

With his gregarious, laddish ways he proved popular among his clients and fellow traders on the metals exchange. Mr Farage, who started work just before the "big bang" in the City, earned a more than comfortable living, but he had another calling - politics.

He joined the Conservatives but became disillusioned with the way the party was going under John Major. Like many on the Eurosceptic wing, he was furious when the prime minister signed the Maastricht Treaty, stipulating an "ever-closer union" between European nations.

Mr Farage decided to break away, becoming one of the founder members of the UK Independence Party, at that time known as the Anti-Federalist League.

In his early 20s, he had the first of several brushes with death, when he was run over by a car in Orpington, Kent, after a night in the pub. He sustained severe injuries and doctors feared he would lose a leg. Grainne Hayes, his nurse, became his first wife.

He had two sons with Ms Hayes, both now grown up, and two daughters with his current wife, Kirsten Mehr, a German national he married in 1999.

Months after recovering from his road accident, Mr Farage was diagnosed with testicular cancer.

He made a full recovery, but he says the experience changed him, making him even more determined to make the most of life.

The young Farage might have had energy and enthusiasm to spare - but his early electoral forays with UKIP proved frustrating.

At the 1997 general election, it was overshadowed by the Referendum Party, backed by multimillionaire businessman Sir James Goldsmith.

'Used car'

But as the Referendum Party faded, UKIP started to take up some of its hardcore anti-EU support.

In 1999, it saw its first electoral breakthrough - thanks to the introduction of proportional representation for European elections, which made it easier for smaller parties to gain seats.

Mr Farage was one of three UKIP members voted in to the European Parliament, representing the south-east of England.

The decision to take up seats in Brussels sparked one of many splits in the UKIP ranks - they were proving to be a rancorous bunch.

Mr Farage scored a publicity coup by recruiting former TV presenter and ex-Labour MP Robert Kilroy-Silk to be a candidate in the 2004 European elections, but the plan backfired when Mr Kilroy-Silk attempted to take the party over.

It was a turbulent time for UKIP but in that year's elections it had increased its number of MEPs to 12.

In 2006 Mr Farage was elected as leader, replacing the less flamboyant Roger Knapman.

He was already a fierce critic of Conservative leader David Cameron, who earlier that year had described UKIP members as "fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists".

Mr Farage told the press that "nine out of 10" Tories agreed with his party's views on Europe.

Asked if UKIP was declaring war on the Conservatives, he said: "It is a war between UKIP and entire political establishment."

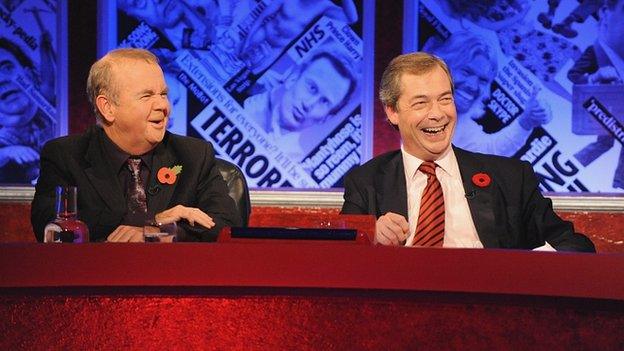

At the 2009 European elections, with Mr Farage becoming a regular fixture on TV discussion programmes, UKIP got more votes than Labour and the Lib Dems and increased its number of MEPs to 13.

But the party knew it could do little to bring about its goal of getting Britain out of the EU from Brussels and Strasbourg - and it had always performed poorly in UK domestic elections.

In an effort to change this, Mr Farage resigned as leader in 2009 to contest the Buckingham seat held by House of Commons Speaker John Bercow.

He gained widespread publicity in March 2010 - two months before the election - when he launched an attack in the European Parliament on the President of the European Council, Herman van Rompuy, accusing him of having "the charisma of a damp rag" and "the appearance of a low-grade bank clerk".

It raised Mr Farage's profile, going viral on the internet, but made little difference to his Westminster ambitions. He came third, behind Mr Bercow and an independent candidate,

Mr Farage's chosen successor as leader, Lord Pearson of Rannoch, was not suited to the cut and thrust of modern political debate and presentation, and UKIP polled just 3.1% nationally.

But there was a far greater personal disaster. On the day of the election an aeroplane carrying Mr Farage crashed after a UKIP-supporting banner became entangled in the tail fin.

He was dragged from the wreckage with serious injuries.

After recovering in hospital, he told the London Evening Standard the experience had changed him: "I think it's made me more 'me' than I was before, to be honest. Even more fatalistic.

"Even more convinced it's not a dress rehearsal. Even more driven than I was before. And I am driven."

Mr Farage decided he wanted to become leader again and was easily voted back after Lord Pearson resigned.

Europe, and particularly migration to the UK from EU countries, has been a growing political issue since the enlargement of 2004.

Mr Farage has increased UKIP's focus on the immigration impact of being in the EU.

In doing so he wants to be seen as tribune for the disenfranchised, not just the older, comfortably off middle classes alienated by rapid social change caused by mass immigration, but working-class voters left behind in the hunt for jobs and seemingly ignored by the increasingly professionalised "political class".

Referendum pledge

At last year's local elections in England UKIP won more than 140 seats and averaged 25% of the vote in the wards where it was standing.

It has come second in parliamentary by-elections in Eastleigh and in Wythenshawe and Sale East.

Under pressure from many in his own party - some fearful of UKIP's rise - to address the EU issue, Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron has promised an in-out referendum on the membership if his party wins the next election.

But Mr Cameron, Labour leader Ed Miliband and, of course, Nick Clegg have all said they would prefer to remain "in" rather than "out".

Mr Farage stands four-square against this.

UKIP is aiming to win the most votes, and seats, at the European elections. From polling just 0.3% at the 1997 general election, it would represent amazing progress.

Mr Farage, who professes a love of all things European, except the European Union, and other "homogenising" projects, would certainly raise a glass or two to that.

- Published3 April 2014

- Published2 April 2014

- Published2 April 2014

- Published2 April 2014