Profile: Nick Clegg

- Published

Few politicians have experienced a more rapid rise - and equally rapid fall - in popularity than Nick Clegg and yet managed to stay in the game.

The Liberal Democrat leader burst into the public consciousness as the star of the 2010 general election TV debates, sparking a wave of "Cleggmania", which did not last until polling day but did effectively establish him as a fresh, new face on the political scene.

He took his party into government for the first time in a generation, in coalition with the Conservatives, becoming deputy prime minister in the process.

But by the end of 2010, he was being burned in effigy by student protesters.

From being barely recognised outside Westminster, to being hailed as Saint Nick to becoming Public Enemy Number One, all in the space of 12 months, is quite a rollercoaster ride.

And although his party has never recovered from the battering it took in the opinion polls over his U-turn on tuition fees, with some members fearing it will be wiped out at the next general election, his position as leader looks secure enough, for now.

So what is it about Nick Clegg that inspires such extremes of emotion? And how did he get to the top of his party?

Mr Clegg has always presented himself as an anti-establishment figure, somebody who wants to shake-up the status quo, yet his background and political apprenticeship could not be more conventional and middle-class.

Born in 1967 in Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire, he is the third of four children of Nicholas Peter Clegg CBE, chairman of United Trust Bank.

'Drunken prank'

He was educated at Westminster school, a few hundred metres from the Houses of Parliament, one of the country's top private schools.

Friends recall a "spotty" but self-confident teenager with a keen sense of fun, who sought out the limelight in school plays.

The one blot in his copybook came when, as a 16-year-old exchange student in Munich, he and a friend were arrested for setting fire to a collection of rare cacti belonging to a professor.

Mr Clegg has described the incident as a "drunken prank," of which he was "not proud". He was sentenced to community service and had to spend the summer digging gardens.

After studying anthropology at Cambridge, he briefly became, in his own words, a "ski bum" and tried to write a novel, which he later described as "embarrassingly bad".

He took a road trip across America with his friend Louis Theroux, the documentary maker, and his novelist brother, Marcel, during which, to the amusement of the Theroux brothers, he practised transcendental meditation. Other celebrity friends include Helena Bonham Carter, who acted in a play with him at university.

After completing a postgraduate scholarship at the University of Minnesota, Mr Clegg began a career in journalism as an intern in New York on left-wing magazine The Nation.

'Class system'

He then had a spell in Hungary, where he was sent as the first winner of the Financial Times David Thomas Prize, before going to work for European Commissioner Leon Brittan in Brussels.

Much has subsequently been made of the fact that Lord Brittan is a former Conservative cabinet minister, but the Tory grandee says young Clegg always resisted attempts to recruit him to the Tory Party.

Mr Clegg has said his politics were forged in the Thatcher era - when he opposed everything the then Tory leader stood for. He recently told the BBC that he had never been aware of any attempt by Lord Brittan to recruit him.

He cites his Dutch mother, Hermance van den Wall Bake, a special-needs teacher who was imprisoned by the Japanese as a child during World War Two, as the biggest influence on his politics.

"I became a liberal not in a library, but over the dinner table, in the car, in the park, in conversation with my mum," he once told the Lib Dem Voice website.

"I hope I've inherited some of my mum's unerring compassion, her ability to see potential in everyone, her despair at the class system, and her total belief in justice."

Mr Clegg's father is half Russian and his aristocratic grandmother fled St Petersburg after the tsar was ousted.

He is married to a leading commercial lawyer, Miriam Gonzalez Durantez, a former Middle East expert at the Foreign Office, whose father was a conservative senator in the Spanish parliament.

Future leader

The couple, who met while studying at the College of Europe in Bruges, live in south-west London with their three children.

At the European Commission, Mr Clegg managed aid projects in the poorest parts of Russia and led the EU's negotiations on China and Russia's entry into the World Trade Organisation.

A brief spell as a lecturer at Sheffield University followed before he became a Liberal Democrat MEP in 1999.

He was talent-spotted by the then Lib Dem leader Paddy Ashdown and it was not long before he was swapping Brussels for Westminster.

Despite his relative inexperience, he was tipped as a future leader almost from the moment he arrived in the Commons in 2005, as the MP for Sheffield Hallam.

He did not have to wait long to get his chance, when Sir Menzies Campbell unexpectedly quit as leader in 2007.

Mr Clegg was part of a new generation of Lib Dem MPs who saw themselves as classical liberals - believers in free trade, free markets and individual liberty.

But despite starting as firm favourite, he was nearly beaten to the leadership by a figure from the left of the party, Chris Huhne, after a closely fought, and at times fractious, contest.

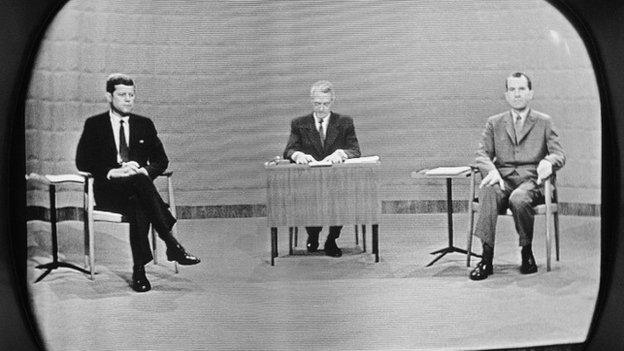

The defining moment of Mr Clegg's political career came in the May 2010 general election campaign, when he took part in Britain's first televised leaders debates.

Mass defection

The Lib Dem leader outshone David Cameron and Gordon Brown in the first of their three encounters, sparking headlines claiming he was the most popular politician since Winston Churchill and vitriolic attacks from right-leaning newspapers who had previously ignored him.

The expected poll boost largely failed to materialise, but the Lib Dems still had enough MPs to effectively hold the balance of power in a hung Parliament when the votes had been counted.

To the surprise of many outside Westminster, who tended to assume the Lib Dems were closer to Labour, he entered a formal coalition with the Conservatives.

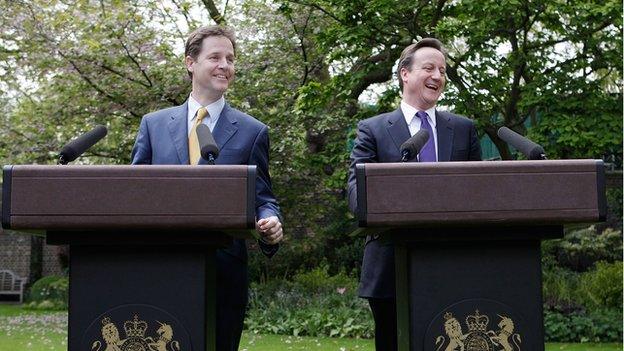

His joint press conference with Conservative leader David Cameron in the Downing Street rose garden, with the two new best friends smiling and joking together, took on an iconic status - and would come back to haunt him when, inevitably, the coalition going got tough.

Mr Clegg reasoned that he could secure more of the Lib Dems' priorities in coalition with Mr Cameron than with Labour - and he won the backing of his party for the deal at a special conference.

He won a "pupil premium" to pump money into schools in disadvantaged areas, a referendum on electoral reform - which he lost - and an increase in the tax-free allowance to £10,000.

In return, he accepted the scale and speed of the Conservatives' spending cuts, sparking a mass defection of left-wing Lib Dem members and voters.

Political gamble

He also decided to support a rise in tuition fees, something he had opposed in opposition. It was a move that split his MPs, led to much agonising among his ministers and a cry of betrayal from students who had voted for him - and who now took to the streets in protest.

Mr Clegg later attempted to repair his newly toxic image by apologising for the U-turn, arguing that some policies had to be sacrificed in a coalition but that more pupils from poor backgrounds were going to university as a result of it.

Despite going viral on the internet, after it was set to music by pranksters, the apology had little impact on the Lib Dems' poll ratings, which had dropped from 23% at the 2010 election to around 10%.

A by-election victory in Eastleigh, triggered by the enforced resignation of his old leadership rival Chris Huhne, gave the party a glimmer of hope.

And Mr Clegg began to build a new narrative for it - abandoning his former claim that the Lib Dems were aiming to form a government on their own - and replacing it with the claim that Britain needed Lib Dems in government to act as a brake on the wilder excesses of the big two parties - to "anchor" British politics to the centre ground.

It was a bold move - effectively arguing for a permanent seat at the top table - and some saw it is wildly over-ambitious given the party's position in the polls.

But Mr Clegg has always relished a political gamble, the latest being his decision to challenge UKIP leader Nigel Farage to debates on whether the UK should be in the EU, which has generated much needed publicity for the party ahead of May's European elections.

- Published3 April 2014

- Published2 April 2014

- Published2 April 2014

- Published2 April 2014