Where is the inspiration in this election?

- Published

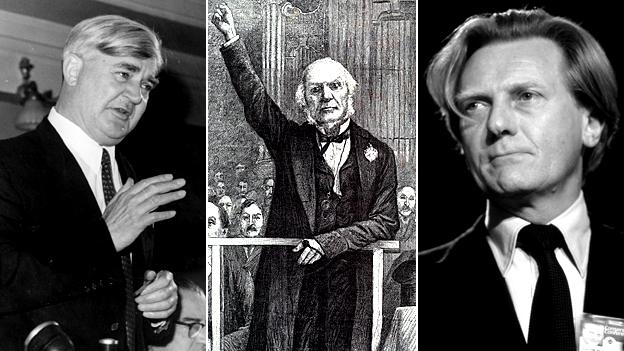

Bevan, Gladstone, Heseltine: where are the great political performers of today?

Inside the vast space of the Al Masjid ul Husseini mosque, in Northolt, north west London, pathways and rooms are being created at bewildering speed as barriers are shifted and rearranged, passed overhead in a happy chaos.

Men in pristine, white dishdashas and neat embroidered caps race from one place to another, watched by women in long dresses of many colours, decorated with flowers and intricate designs.

"It is the happiest day of the year," one woman tells me, smiling broadly.

The spiritual leader of the Dawoodi Bohra Shia sect is on a rare visit, external from India.

Infectious, joyous excitement crackles through the air. I had come looking for passion and big ideas - and I have found them.

But I was seeking political, not spiritual enlightenment, and the answer to a question that puzzles me.

I'm here because the shadow justice secretary, Sadiq Kahn, the man co-ordinating Labour's campaign in the English capital, is campaigning here.

His ambitions seem modest. He says: "There are more than 2,000 people visiting the mosque today, and it is good chance to meet ordinary punters and hear from them.

"I don't ram politics down their throat, I just want to be seen as a normal human being.

"There are a lot of people who think, 'It doesn't matter what colour party you are, Tory, Labour, or Lib Dem, you're all the same.'

"The challenge we have is to be relevant and speak their language."

Perhaps this feeling among politicians that they have to struggle to appear even vaguely relevant explains the thing that has been puzzling me.

That is the almost total lack of passion, vision or big ideas.

It does not seem to make even strategic sense. Just about everyone agrees the most likely outcome of this election is a hung Parliament and it is almost impossible to predict who will end up as prime minister.

Sadiq Khan is co-ordinating Labour's campaign in the capital

But the big parties are behaving as if "Steady as she goes" is their campaign motto and "Caution" is their watchword.

Take those messy "debates".

To put it mildly, no-one is arguing Ed Miliband is such a towering presence that he can overwhelm any opponent simply by sitting in the same room.

But the prime minister has behaved as though one quip, one well aimed barb from the Labour leader's lips will leave him flapping and floundering and eject him from Downing Street.

This is not personal cowardice: it is a political strategy.

You would think when they are neck and neck, they would be straining every sinew to get ahead by a head, but there are as yet no flourishes, no thunder, no hint of danger.

It as if the very soul of the body politic has been infected by austerity, where inspiration might seem just too extravagant and the vision thing embarrassingly exuberant, and that our leaders have come to believe voters will view the paralysis of poltroons as endearing humility.

Some argue that it is another sign that our politics is broken, not fit for purpose.

Deep structural problem

One of David Cameron's former speech writers, Danny Kruger, external, now with a criminal justice charity, put this eloquently on BBC Radio 4's World This Weekend programme.

"We've got a deep structural problem in our politics, which accounts for a lot of this," he said.

"We've got two parties which are founded in a 19th Century industrial dispute which doesn't really exist any more.

"They were founded on the idea of capital versus labour, which isn't what most people feel any longer, and yet, because of the longevity of the party system, people are still attached to these labels, and that completely alienates and disenfranchises the great majority of people who are thinking about other things."

He added: "'I don't think there are a great deal of differences between the parties.

"What you have is a lot of insults being thrown around, but this election is not about major differences - the policy differences are pretty minor, about exactly when the deficit might be paid down.

"What we are being offered is a choice between a party that is accused of being heartless and a party that is accused of being incompetent.

"That doesn't feel like a big ideological battle people can engage with."

Ken Livingstone warned people were angry

Former Mayor of London Ken Livingstone has a rather different take, but he also thinks the rise of UKIP and other parties reflects a reality the big parties are ignoring.

"In a sense now the political gap is bigger than it has been for the last 20 years, but that isn't getting over to people," he says.

"I am doing a lot of canvassing in key marginals, and there is an angry, white working-class vote, where the jobs they used to do have been wiped out, they are insecure, we haven't built homes to rent for 30 years, the quality of their life has dramatically changed, and they blame politicians for that."

Humility is key

Back at the mosque, Mr Khan offers a practical politician's justification for the lack of big ideas - people no longer trust such grand visions.

"It is about humility," he says. "We all seem cocky, we all seem to think we know all the answers, and people have switched off.

"The challenge we've got now is just persuading people to be registered to vote.

"Often people say, 'Why should I be bothered?' That's step one, step two is persuading them to actually vote, step three is persuading them to vote Labour.

"I take it in those steps, because if you go straight to step three, people just aren't listening."

He is perhaps right - the struggle is to simply to persuade people that politics matters.

This found an echo on the Today programme when presenter John Humphrys bemoaned the lack of hope and both former Tory MP Matthew Parris and current Labour MP Tessa Jowell suggested people wanted not some grand idea of hope but specifics - a new bridge, more houses, something tangible and achievable.

Change is needed

Mr Kruger thinks all this mean that change could be in the air.

He says: "We've got these dead shells - parties founded on an old ideological difference which retains this weird power, and they just need to fall away.

"It might be that this election, which is going to produce some weird outcome, will cause these party labels, Conservative, Labour, Liberals to fall away and we might find some new settlement that will relate more meaningfully to people."

Perhaps we should understand, if not applaud, the modesty of politicians who feel their class is guilty of so many -isms, so much ideology, so many broken promises that they must be penitently narrow in their pitch.

The two main parties seem to be making the drab offer of the last two wallflowers at the dance: "At least I'm better than that."

They cannot be surprised if voters turn their back and go home alone.