Senior level gender pay gap 'higher now than in 2005'

- Published

The gender pay gap for women in full-time senior employment is higher now than it was in 2005, the Commons Women and Equalities Committee has been told.

Ann Francke, from the Chartered Management Institute, cited research suggesting that closing the gap could boost the UK economy by £35bn by 2030.

MPs were taking evidence on the causes of the problem, and ways to fix it.

More flexible working, better childcare and cultural change within companies were cited as ways to boost equality.

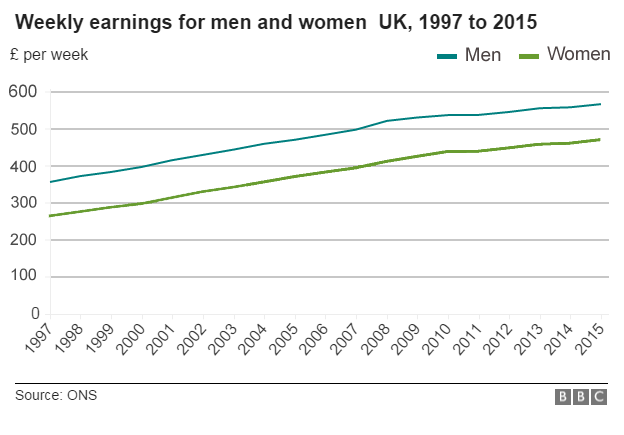

According to the Office for National Statistics, the gap between men and women's pay for full-time workers was 9.4% in April 2015, compared with 9.6% in 2014.

While that was the narrowest difference since the figures were first published in 1997, there has been little change overall.

Meanwhile, the World Economic Forum believes it will take another 118 years - or until 2133 - until the global pay gap between men and women is finally closed.

Cultural shift

New legislation will soon require companies in England, Scotland and Wales with more than 250 staff to publish details of male and female pay, as part of government efforts to reduce the pay gap.

Ann Francke, chief executive of the Chartered Management Institute, said that while welcome, cultural change in organisations was also needed.

She told the committee that the higher up a company the lower the female representation - a pattern which she said had remained unchanged in 10 years.

"The notion which is often put forward that 'it's fine because we solved the gender pay gap at the low levels and it will go away' is actually flawed," she said.

She said the CMI had measured gender pay at junior, middle and senior levels for 40 years, "and I can tell you that in 2005 the pay gap for senior women was less than it is today".

"The reasons for that are cultural" she added, and said it was a "broader" problem than the "motherhood penalty", pointing out that non-mothers are also affected.

She added: "It's about the culture of success, about how we define who is successful, it's about this long hours presenteeism rather than designing work around the modern lifestyle."

Companies that embraced more progressive policies "absolutely benefit economically", including through higher productivity, she told the committee.

Also giving evidence, Confederation of British Industry director Neil Carberry said that closing the pay gap was not only "the right thing to" but also had "commercial upsides", saying research had shown diverse groups "make better decisions".

"From a labour market point of view the fact that we have a gender pay gap is a sign of an inefficiency, by definition and therefore resolving it is commercially important to our members," he added.

Flexible working

The committee, which was holding its first inquiry into the gender pay gap, also heard from academics, economists and journalists.

Chris Giles, economics editor at the Financial Times, said progress had been made in narrowing the gap, telling MPs that it had disappeared for full-time for women in their 20s and 30s.

He said the gap had "halved" for women in their 40s, but there had been "no improvement" for women in their 50s.

But he added: "It's very clear that the move part-time or interrupted career is very severe for your lifetime pay and for your retirement pay."

Concerns were raised about the difficulties women faced in returning to work after maternity leave

He was among several witness to call for more flexible working, saying it needed to be made easier for women to come back from maternity leave to a full-time role.

Professor Jill Rubery, from Manchester University, added: "We need the right to return to full-time working not just the right to request to work part-time."

There was also broad support for pay audits and mandatory gender pay reporting, with several of the witnesses saying this improved transparency.

Meanwhile, Dr Alison Parken, from Cardiff University, warned: "Women are getting firsts and 2:1s at a higher rate than men but they are much more likely than men to work in jobs and sectors below their qualifications level."

Monika Queisser, head of social policy at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, said research showed the gender pay gap was smaller in countries that offered better public childcare and parental leave arrangements.

- Published19 November 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Published25 October 2015