Would Westminster benefit from tax transparency?

- Published

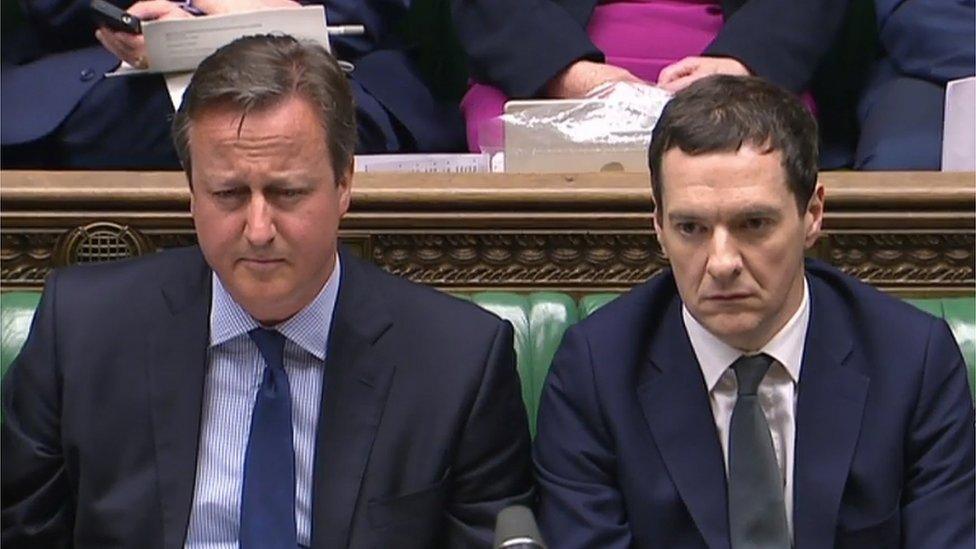

David Cameron and George Osborne have published their tax returns

It may be easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God, but wealth has never been an insuperable barrier to a parliamentary career.

The super-rich feature in both Houses and, following David Cameron's post-Panama Papers publication, external, we might soon have the voyeuristic pleasure of inspecting their tax returns.

At the moment the prime minister is trying to hold a line; that he and Chancellor George Osborne should reveal their tax affairs because they are the people who set tax policy - and that others, by implication, should not have to do so.

But the pressure for disclosure might not stop there; what about lesser Treasury ministers, business ministers, any ministers involved in spending decisions, which is pretty much all of them?

Or MPs on the Treasury Committee, the bill committees for finance bills and city regulation measures? What about their opposition and minor party shadow ministers?

The ripple effect of the principle could soon engulf most of parliament - and could then continue outward, encompassing major public officials, industry regulators and the like.

The ripple would probably manifest itself as peer pressure - "X has published all his tax details, why haven't you, minister?" - well before any rule change was pushed through to require publication.

Already, Boris Johnson, who was under no particular pressure to reveal his tax affairs, has gone public,, external revealing an impressive income as a columnist and author.

And in the process he has made it very hard for future rivals for the leadership of the Conservative Party not to follow suit. By the next election tax disclosure by candidates could be an almost universal expectation, as it is in America.

Of course, MPs already have to disclose their earned income in the Register of Members Income, so any employment income - which covers things like paid directorships, earnings as a member of Lloyds, salaries and fees paid in kind have to be there - but the rules specifically do not require them to declare "Income received by way of dividends."

Sir Alan Duncan suggested that forcing disclosure of finances could lead to a Commons filled with under-achievers

The register is designed to reveal where interests lie - rather than how much income is generated by those interests. So MPs must register shares when they amount to more than 15% of the share capital of a company, or are valued at more than £70,000. And that includes any shares which are managed by a trust, other than, for obvious reasons, a blind trust.

Changing that requirement would expose their income from assets - shares, trusts, whatever, to the public gaze - but it's an extension of what already happens with other forms of income, not a new principle.

Some would doubtless find the glare of scrutiny uncomfortable; either because they just don't like entirely innocent financial matters being made public, or, perhaps in a few cases, because something embarrassing would be revealed.

And politically, there is clear evidence, external that the voters are less keen on rich candidates - especially if the extent of their wealth is available in footnoted detail, for opponents to rub their noses in.

As candidates' earnings increase, so their popularity declines, wealth is an especial negative for women, working-class and Labour and Lib Dem respondents voters - while Conservative voters are less put off by wealthy candidates, but they draw a sharper distinction between the source of income than others.

William Hague: Churchill's finances are harder to defend than Cameron's

Remember, too, that the disclosure would bring to light things like gift-aid donations and joint arrangements with spouses and relatives, who might think they were none of the public's business.

Some people might even be deterred from standing for parliament or entering government - but a bigger, but more subtle, danger is that irritation at a forced disclosure might feed into a more general disgruntlement and make MPs harder to manage and less whip-able.

And in the current fractious Westminster climate, that is not nothing.

Politicians' taxes: who's published what?

David Cameron: A summary, external of his tax returns from 2009 to 2015

George Osborne: His tax return for 2014-2015, external

Jeremy Corbyn: His tax return for 2014-2015, external

Nicola Sturgeon: Her tax return for 2014-2015

Boris Johnson: A summary of his tax returns, external for the past four years

John McDonnell: His tax return for 2014-2015

Leanne Wood: Her tax return for 2014-2015, external

- Published10 April 2016

- Published11 April 2016