How government is changing under Theresa May

- Published

Theresa May has been prepared to give ground in key cabinet committees

Theresa May sat at the same cabinet table for six years. But with sixty days in charge, government has changed already.

It's not just her famed forensic style, or her demands for detail.

But as ministers and their teams knuckle down to the new era, the features of Theresa May's administration are emerging.

Members of the cabinet agree there is now more discussion, more consultation with colleagues. One said there is less of a cosy Cameron inner circle, with others on the periphery.

But in its place is what another described as a "more hierarchical" system with No 10 "very much in charge". Several ministers told me there are broader discussions but a narrower decision making process follows.

Kindred spirits

Another member of the cabinet warned the new government could be "bottlenecked", with its much tighter, less trusting grip.

But senior Whitehall sources point to three new cabinet committees as the place where power will really reside. And already in those meetings the prime minister is understood to have given way.

One source close to her told me she was unlikely to "significantly push against" a consensus at the committees on Brexit, the economy and social reform even if it goes against her views. It's worth noting, however, she chairs all three.

As with any new administration it's not just the ministers who play musical chairs, but the advisers too. All sorts of suggestions too have been made about Theresa May's joint chiefs of staff, claims that they stop everything in its tracks, wield too much power and don't use it wisely.

It's true both Fiona Hill and Nick Timothy are intensely loyal, after years advising her as home secretary, before spells in think tanks and public affairs. Several ministers are clearly frustrated about how much they are being pushed to share.

The prime minister's relationship with her chancellor is different from their predecessors

But one source who has worked with several different prime ministers says a lot of the chatter about the new team of advisers is caricature. While May's team are tough gatekeepers, they believe there is so far, nothing abnormal or out of the ordinary about the access and influence they have. I'm told that Timothy and Hill have not attended the last couple of cabinet meetings, to dispel the gossip that they are somehow the ones really in charge.

But the most critical relationship at the very top of government is different too. Theresa May and the Chancellor Philip Hammond are described as kindred spirits - serious, unflashy Tories who have worked their way up.

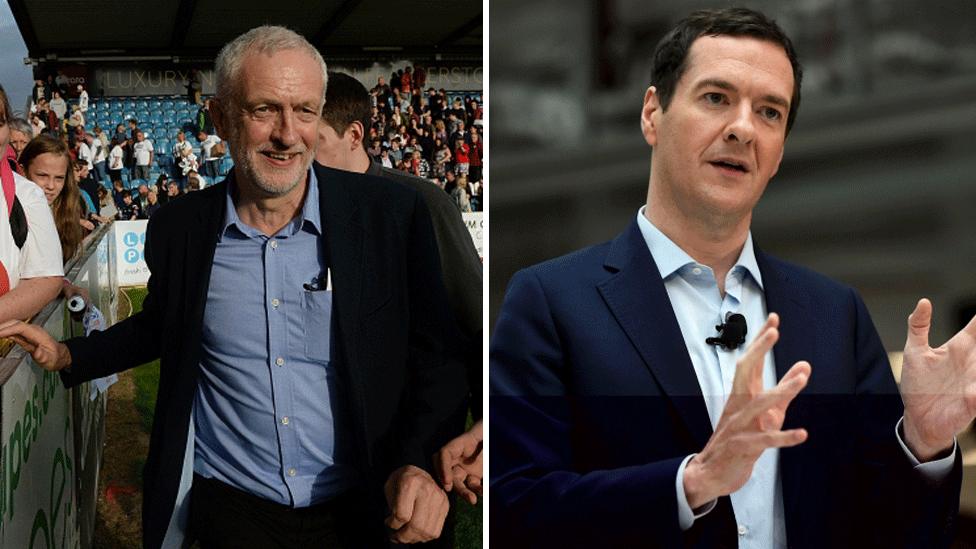

But theirs is not a joint project like David Cameron and George Osborne's - the prime minister sees him neither as the government's chief political strategist nor as a co-chair of the government.

One cabinet minister said Philip Hammond is "the finance minister not the chief executive".

Plenty of prime ministers have been stricken by disagreements with their next door neighbours in No 11. There's little sign of that, with sources suggesting Philip Hammond is normally the first to speak in any cabinet discussion and he and the prime minister meeting frequently.

'More traditional'

But the change in relationship between Number Ten and the Treasury is fundamental. One cabinet minister told me that in six years they had never attended a meeting where Mr Osborne and Mr Cameron hadn't already agreed their position beforehand.

The relationship between Mr Hammond and Mrs May is described as "more traditional….it was George and David who were the exception". But that, even in these early days, could change the complexion of the government in charge.

Many in Westminster might however see it as an advantage that the chancellor does not have what one minister described as "imperial ambitions". Allies say Mr Hammond will be focused on the economy, not on how he can become prime minister.

Having a chancellor who is less wedded to the prime minister's hopes and ambitions will make a difference. The Treasury will still be a powerful institution, but under George Osborne, and indeed Gordon Brown before, No 11's tentacles had spread further and further across Whitehall.

Under Philip Hammond and Theresa May power might flow the other way.

- Published13 September 2016

- Published13 September 2016