Brexit battle in Supreme Court: Key points

- Published

The UK Supreme Court has finished a historic four days of hearings on Brexit - and who has the power to trigger it. Now the 11 justices will deliberate on whether government or Parliament has that power.

We are expecting the judgement in January.

What must the Supreme Court decide?

Philanthropist Gina Miller is one of two claimants to challenge the government

The government was appealing against a really simple challenge won by two claimants, investment banker and philanthropist Gina Miller and London hairdresser Deir Dos Santos.

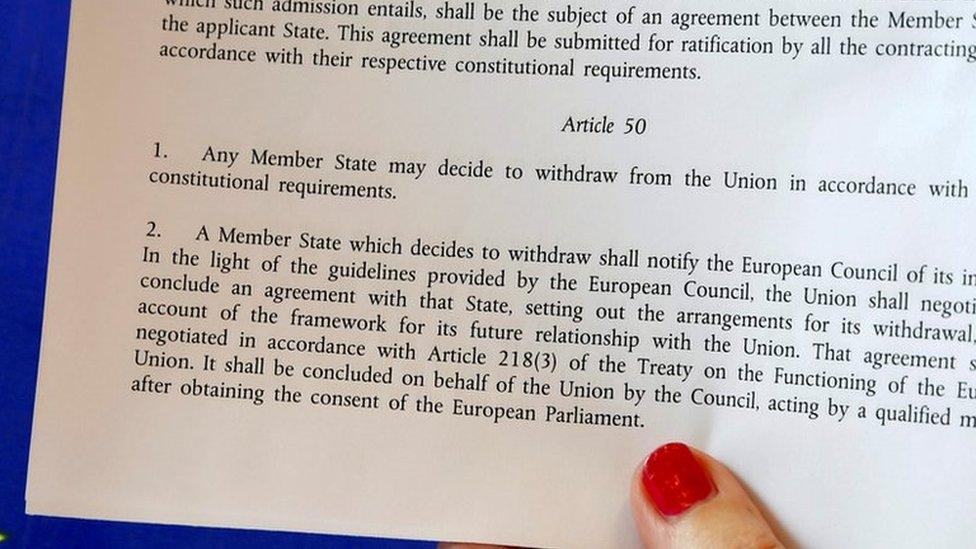

In the High Court, they jointly challenged the government's presumption that it had the right to trigger "Article 50", the exit clause in the treaty that makes the UK a member of the European Union.

They argue, instead, that it is for Parliament to say what happens following the Brexit referendum vote.

The Supreme Court's eventual judgement, whatever it may be, will not overturn the referendum result: it will simply determine which course towards exit is lawful.

What were the government's arguments?

James Eadie QC led for the government. He is the First Treasury Counsel - the government's top barrister in legal scraps. On Monday he kicked off the appeal making a simple point: ministers have the power to trigger Brexit under the "royal prerogative".

The prerogative is executive power that used to belong to kings and queens - but as British democracy developed down the centuries, passed to an elected Parliament.

Treaties are an exception. They're negotiated and agreed by government ministers under the power of prerogative.

Mr Eadie argued the following:

Ministers negotiated the treaty that led to joining the then EEC in 1972

They have the power to withdraw from that treaty - not least because the outcome of the referendum instructed them to do so

If Parliament had intended ministers to not have the power to do so, they would have legislated to take it away

Mr Eadie said the 1972 act did not carry the same weight as other domestic law that could only be undone by Parliament. It's "neutral" on whether the UK should be a member because its job is to be simply a "conduit" to introduce EU laws or rights into our domestic law.

Top QCs David Pannick (L) and James Eadie (R) are going head to head

From time to time the rights of being in the EU have been changed as the international agreement between the governments has developed. Therefore, membership can also be changed by the government - so the 1972 act ceases to be relevant.

Best line? The entire case was a "constitutional trap" taking judges dangerously close to making up laws themselves.

Most vulnerable? Attacked repeatedly by the other side for lack of evidence that ministers ever had the prerogative power to take away the right of EU membership.

The case against the government

David (Lord) Pannick QC led the response for Gina Miller. He said that the government was reducing the 1972 act at the bedrock of EU membership to "a lesser status than the Dangerous Dogs Act".

He said there were seven grounds why the government was wrong, including:

The 2015 Referendum Act didn't give ministers power to trigger Article 50. They have no power at all to change the constitution

Government has failed to demonstrate that Parliament expressly handed over power to ministers during the 1972 act. Just because Parliament has been silent on the issue doesn't mean ministers are in control

Over 40 years, myriad rights and laws have been created by EU membership. Only an act of Parliament can take them away

Dominic Chambers QC, for Mr Dos Santos, argued that ministers had lost the executive power to overturn acts of Parliament - including the 1972 membership legislation - as long ago as the 17th Century.

As to Mr Eadie's argument that the 1972 act was not an expression of Parliament's views on membership, Mr Chambers quoted from the then Prime Minister, Sir Edward Heath. He had said entry into the club was a "moment of decision for Parliament".

Best line? "It is so obvious, so basic… These are matters for Parliament." (Lord Pannick QC)

Most vulnerable? Parliament passed the 2015 Referendum Act knowing full well that a vote to leave mandated ministers to get on with it.

The devolution question

A series of QCs argued different points on whether or not the UK's devolution settlement played a role.

For the government, there were submissions that devolution did not have a dog in this fight. While the devolved bodies dealt with EU matters, such as agriculture, Westminster had not devolved international treaty-making powers to Edinburgh, Belfast or Cardiff.

But for the other side, lawyers argued the following:

While Scotland could not veto Brexit, Westminster must properly consult its parliament

The QC for Wales said a "six-year-old" could understand the limits on ministers' power

Two QCs for Northern Ireland argued that Brexit unlawfully unpicked part of the Good Friday Agreement at the heart of the peace process

Only Northern Ireland's people can change their constitutional arrangements - a cast-iron part of their cross-community settlement

Other factors

Helen Mountfield QC argued on behalf of the crowdfunded "people's challenge", brought by members of the public who are concerned about the loss of EU citizenship.

She argued the government's claims for prerogative powers did not stand up to historical analysis. For 300 years those powers had been seeping away.

Manjit Gill QC, for parents and children with a link to Europe - such as foreign-born workers - said they needed certainty and clarity: Brexit by ministerial order would drive a coach and horses through their lives as lawful residents of this country, leaving them as bargaining chips with "bags packed ready to go".

- Published4 December 2016

- Published25 September 2019

- Published24 January 2017

- Published3 December 2016

- Published6 December 2016

- Published5 December 2016

- Published7 December 2016