Boris Johnson: A weakened foreign secretary?

- Published

Boris Johnson denies 'defeat' over sanctions plan

There is, to use Boris Johnson's own lingo, a "whinge-o-rama" raging among the foreign secretary's political opponents and in parts of the press about his performance in the current Syria crisis.

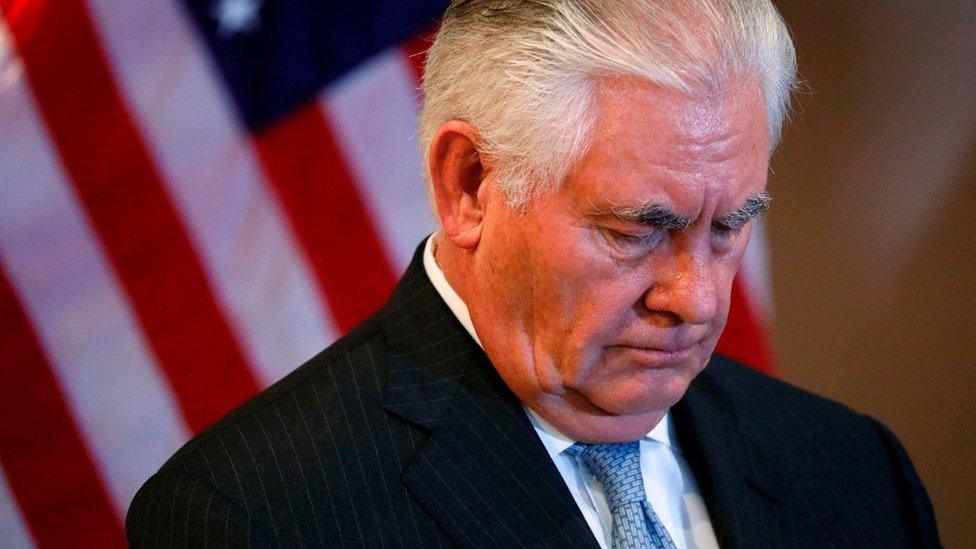

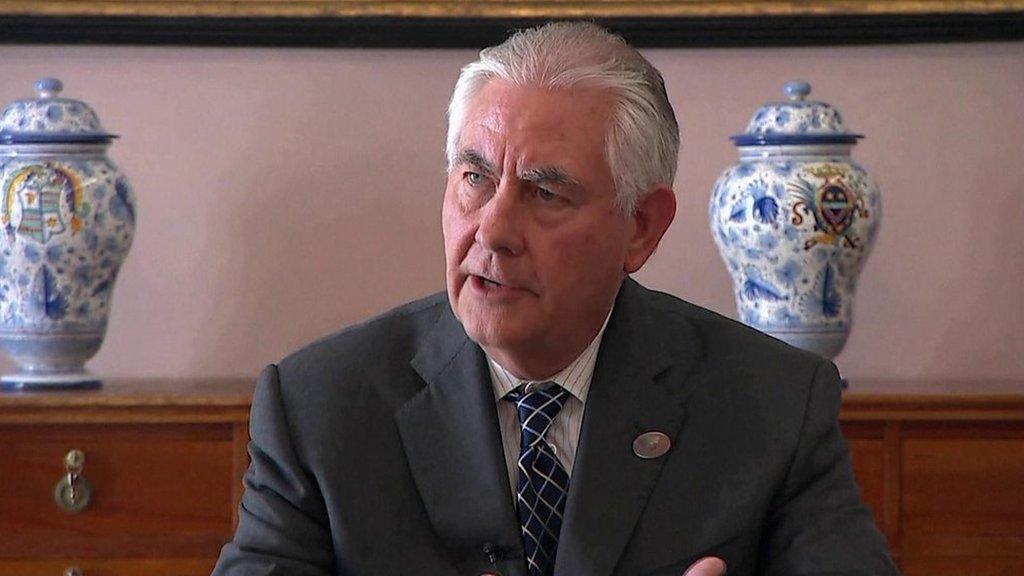

He faces a number of charges. First, he pulled out of a long-planned trip to Moscow after the US missile strike on a Syrian airfield. It was agreed the US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson should go instead.

Poodle, cried his critics.

Next, Team Boris briefed journalists that the foreign secretary wanted to get the G7 to agree new sanctions against Russia at its meeting in the Italian city of Lucca. But Mr Johnson entirely failed to persuade other countries to agree.

Italian Foreign Minister Angelino Alfano said there was no consensus new sanctions would help and argued they could push Russia into a corner.

Mr Johnson's own view of the Syrian conflict seems to have swerved around like a shopping trolley since he became the UK's chief diplomat in July.

Giving evidence to a House of Lords committee at the start of 2017, he signalled a shift in UK policy towards Syria. Mr Johnson said the "mantra" of calling for President Assad to go had not worked and the military space had been left open to Russia to fill.

The Foreign Secretary told peers President Assad should be allowed to run for election as part of a "democratic resolution" of the civil war.

Now, however, Mr Johnson believes the Syrian leader has to go.

How much of this is fair? And what might the episode say about Boris Johnson's standing in Theresa May's government?

First, the UK was a bystander to the Trump administration's missile strike on Syria. The government was given a courtesy call to say it was coming but the UK was not asked to be involved.

Mr Johnson's trip to Moscow (which would have been the first by a British foreign secretary to Russia for five years) was long planned and quickly binned. I understand Mrs May told Mr Johnson it was his call whether he wanted to go or not. After speaking to Rex Tillerson, Mr Johnson and his US opposite number agreed it was best for one man to deliver a single message to Moscow.

Theresa May's decision to give Boris Johnson a top cabinet role surprised many

Mr Johnson then spent a weekend hitting the phones to other G7 countries trying to get a united position agreed ahead of the meeting in Lucca. In its final communique, the G7 did agree to state the Assad regime had to end.

But further sanctions - an idea endorsed by Number 10 - got nowhere. It was clearly a snub to Mr Johnson although government sources insist sanctions have not been taken off the table.

On Wednesday, the Chancellor, Phillip Hammond, said other countries were "less forward-leaning" than the UK on the issue.

Diplomacy is tough. But it may have been unwise for the Foreign Office to suggest sanctions were an ambition when key G7 nations clearly didn't agree.

At the weekend, I was told by Team Boris that he was very relaxed about the sniping and criticism being lobbed his way in recent days. And Mr Johnson has provoked quite a lot since he became foreign secretary, largely because of his use of decidedly undiplomatic language.

He was taken to task by a Swedish MEP in February for calling Brexit a "liberation". A month before that, Mr Johnson warned the French president not to respond to Brexit by administering "punishment beatings" in the manner of a World War Two film.

Guy Verhofstadt, who speaks for the European Parliament on Brexit, branded the remarks "abhorrent and deeply unhelpful". It was several days after President Trump's election that Boris Johnson said it was time for Mr Trump's critics to get over their "whinge-o-rama" - a comment I know left some officials in Brussels agog.

Mr Johnson is always keen to speak with the swashbuckling pluck of the newspaper columnist he once was. His many fans in the Tory party might love it. But even Mrs May has hinted at exasperation.

Theresa May jokes about Boris Johnson the FFS

At the Conservative Party conference last autumn, the prime minister said: "Do we have a plan for Brexit? We do. Are we ready for the effort it will take to see it through? We are. Can Boris Johnson stay on message for a full four days? Just about."

It was a joke. But not many prime ministers joke about their foreign secretary's erraticism. Then in December, Mrs May described Boris Johnson as an FFS - saying that in this case it stood for being a Fine Foreign Secretary (and not the punchy abbreviation for a term of exasperation).

When Mrs May was home secretary and Mr Johnson was London mayor they had a prickly relationship. She then beat him to the job he craved.

Her appointment of the Brexit campaign's most prominent champion to the job of foreign secretary stunned Westminster and it remains one of the most intriguing political relationships within the government.

While happy to clip his wings publicly from time to time, Theresa May also needs Boris Johnson on board as she embarks on Brexit.

A force so effective in persuading Britain to vote to leave the EU is not a politician the prime minister wants sniping from outside the cabinet as the negotiating trade-offs begin.

- Published11 April 2017

- Published11 April 2017

- Published11 April 2017

- Published13 March 2018

- Published11 April 2017

- Published11 April 2017

- Published7 April 2017

- Published10 April 2017

- Published7 April 2017

- Published2 May 2023