Election 2017: How the Tory campaign went so wrong

- Published

Theresa May heads out of Downing Street on her way to see the Queen

At the start of this campaign, we started tracking where the party leaders went, in the hope of picking up clues about what to expect. Had we done this in 2015, it would have helped us spot the Conservatives' big push against the Liberal Democrats. We hoped our experiment might help us avoid a 2015-style shock. So how did it do?

The main thing we have learned is that past performance is a poor guide to the future. The Tories were largely using much of the same team as in 2015 and, once again, they were very well funded. But this evidence implies that the Conservative party campaign in England was an absolute catastrophe, and appalling data and analysis drove them to use their resources poorly.

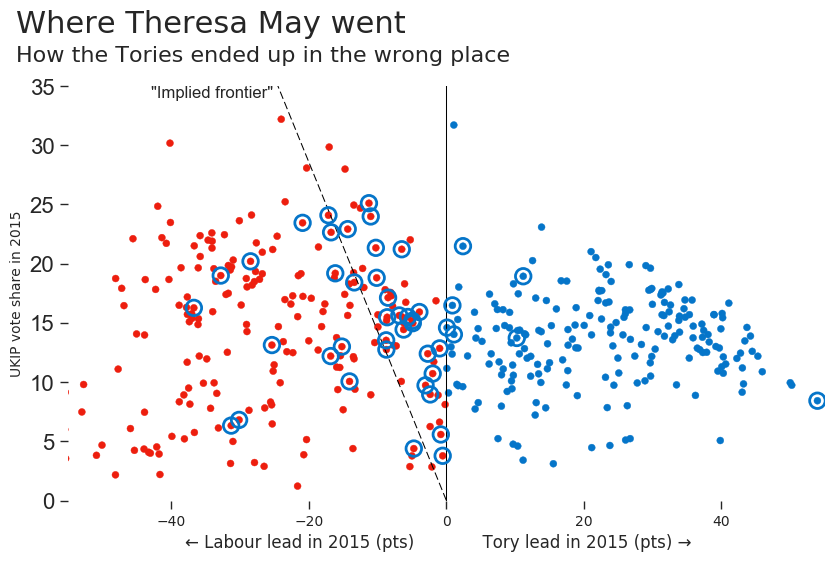

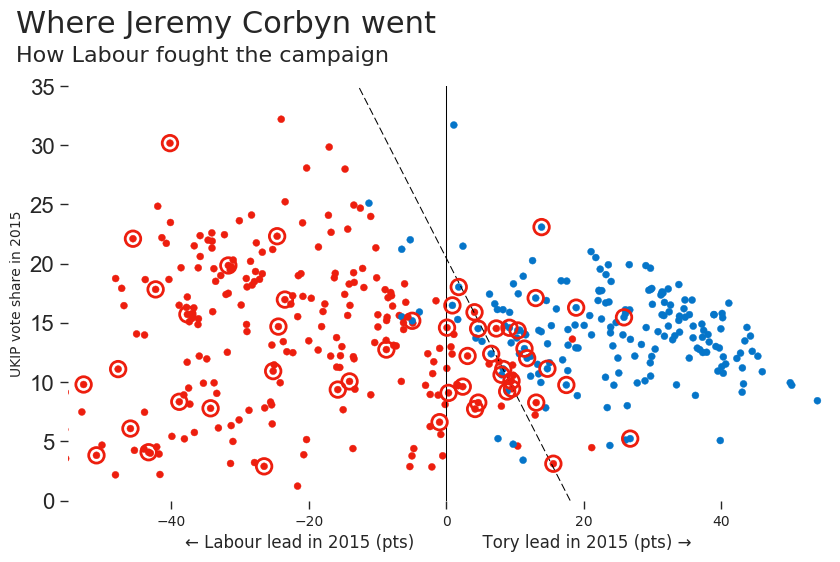

The dots in this graph represent the state of the Tory-Labour battleground before polls opened on Thursday. The higher-up dots show places with more UKIP voters. The furthest left dots show safe Labour seats, and the furthest right dots show safe Conservative seats.

The blue rings show where Theresa May visited. You can see she was more ambitious - going further left - in areas with more UKIP voters.

This stuff matters. While leader visits may be a small part of a party's campaign arsenal, if they were getting that wrong, they were probably getting other campaigning efforts wrong.

So I've drawn in a rough line showing where the Tory campaign thought the battleground roughly was - what we have called an "implied frontier" between the parties. Think of it as the centre of the fight.

Towards the end of the race, the Tories thought it was closer in. Earlier on, they thought it was a bit further out. But treat it as a rough campaign summary. In short, they hoped to flip those Labour seats on the right hand side of the dotted line. This was a strategy aiming for a triple-digit majority - or something close.

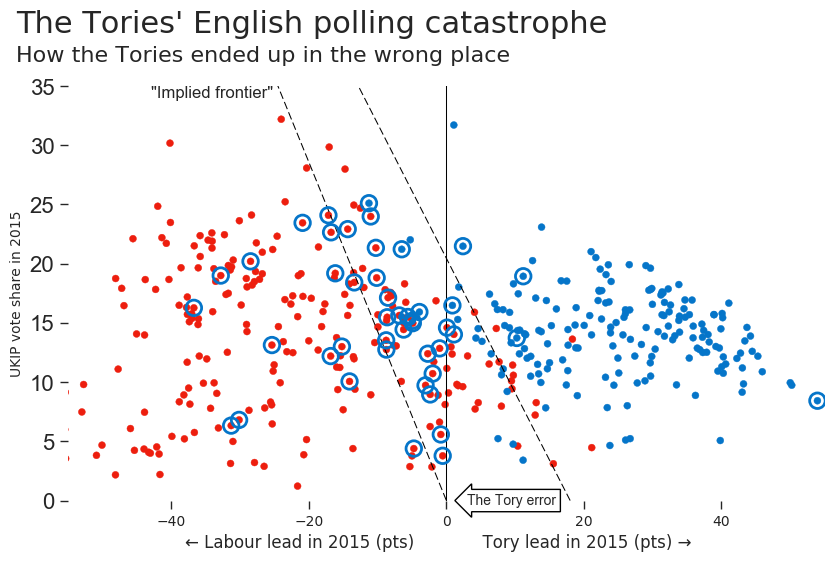

Instead, though, everything went wrong.

In a graph below, I have coloured in the seats by who holds them now. And you can see the actual battleground was in a totally different place. That is the second line I've drawn in. You could draw this line in a few ways, but none of them get close to the Tory implied frontier. And the length of that big arrow is the size of the error. This was a double-digit polling error.

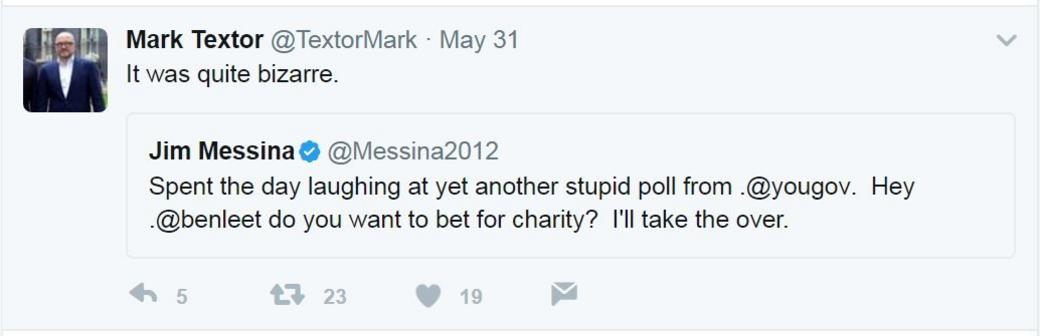

Note, amid this, one further piece of evidence on the importance of polling to this disaster. Last month, YouGov broke from the consensus, external and got close to the real result.

Their model implied a hung parliament. When it was published, the Conservatives' pollsters in England - Mark Textor and Jim Messina - used Twitter to comment on how poor it was. Their reading of the race was, it transpires, way off.

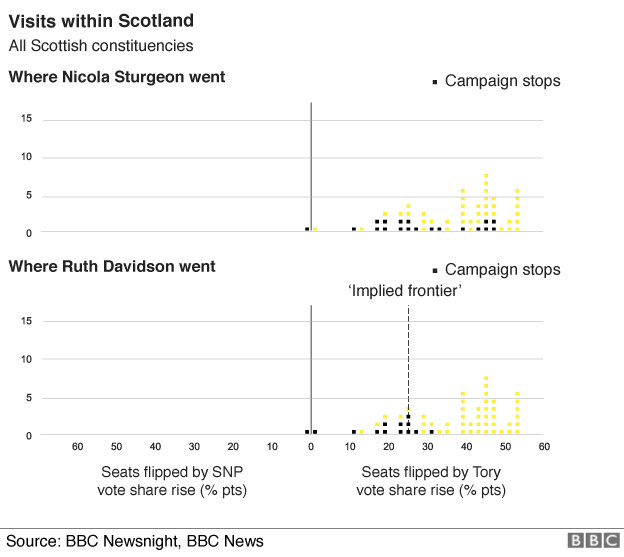

There is another datapoint which supports this conclusion. The campaigns tracker implied the frontier that the Conservatives were aiming for in Scotland was 13 gains. They made 12. And Nicola Sturgeon's patterns of visits suggest she roughly agreed.

So the Conservative campaign there seemed to make sense. It so happens, though, that this was the one part of Great Britain where Mr Messina and Mr Textor were not running the show. The data operation in Scotland was run by James Kanagasooriam of Populus.

Labour's campaigns triumph

Labour's efforts have always been harder to read. They did seem to build events designed to emphasise their presence on local TV bulletins, which made the charts difficult to interpret.

Here, though, is a graph showing Jeremy Corbyn's visits, combined with that same estimate of where the real frontier was.

Look at the right side. However they did it, Mr Corbyn was actually being deployed right there on the front line. The front line is just not where most public polls said it was. Did Labour quietly run a perfect campaign, then?

Labour activists have had a great day, so I hope they do not mind me saying "no".

Before the vote, as I said in my last piece, campaign officials in the party told me that they did not think Mr Corbyn's visits to Tory-held seats should be read as showing their ambitions. He went to places where he was wanted, which was not always a helpful guide to the party's thoughts. In truth, their analysis was, in effect, very close to the Conservative analysis I posted up above.

You can see that elsewhere. When you look at the party's ground operations, they were not matching these visits with resources. I know of MPs who got cut off by the party as dead losses who held their seats comfortably.

Just on Thursday, activists were dispatched to a deep defensive line. Shock gains like Enfield Southgate and Canterbury were shocks to lots of local activists, too, who yesterday were being sent to defend Labour-held seats elsewhere.

To be clear, this is not about people trying to do Mr Corbyn down. I have spoken to people today who could be claiming credit for their foresight, who are wandering around in a state of shock. And, frankly, it is a tribute to Mr Corbyn that Labour did so well, when they put their troops in strange places.

Ian McNichol, Labour's general secretary, and Jeremy Corbyn, Labour leader

What, then, can we learn?

First, these charts explain the epic scale of the Tory shock this morning is explained by how far short of their goals they have fallen. This is simply not a prospect they countenanced

Second, the fight in Scotland was much better understood by the pollsters and parties than the race in England and Wales. And the Scottish Tories are utterly formidable

Third, this was not 2015, when one party knew something the others didn't. This was a result that shocked absolutely everyone.