Five reasons the Home Office is so tough for ministers to run

- Published

- comments

The Home Office is the arm of government where at any given moment the political equivalent of a grenade can go off without notice, potentially destroying the careers of ambitious ministers - and occasionally their officials too.

The latest victim is Amber Rudd, ejected over the Windrush affair, almost exactly 12 years after one of her predecessors, Charles Clarke, was sacked over another immigration fiasco.

Rather than being daunted by the prospect of walking into the department, her successor, Sajid Javid, has promised a new approach.

Not only has he pledged to do "whatever it takes" to put right problems faced by the Windrush generation, he has also disowned the phrase "hostile environment" in relation to immigration control.

But he is also on a steep learning curve, because the Home Office is such a hard place to run. Here are five reasons why the Home Office can be such a poisoned chalice.

1. It's so big and complex, more things can go wrong than anywhere else

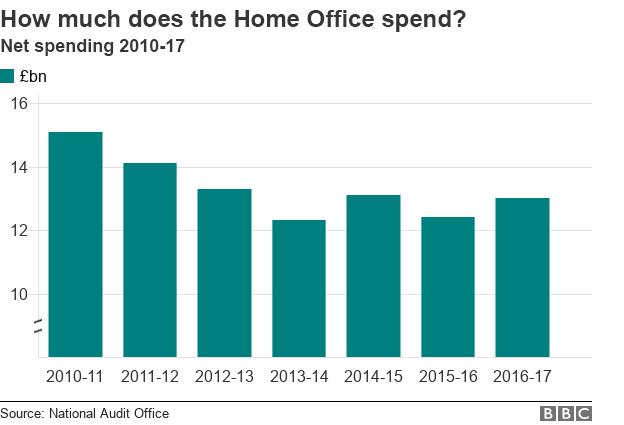

In financial terms, the Home Office is a minnow. It spends about £14bn, excluding income from migration-related fees such as visas and passports.

But it has a long list of responsibilities, which has evolved since the department's creation in 1782, as the National Archives has charted, external.

How the Home Office grew: Key milestones

1782: founded

1793: takes on immigration or "alien" powers

1823: begins to manage prisons (hived off in 2007)

1829: oversees creation of world's first police force

1875: begins to control explosives

1920: first laws to ban firearms

1933: first controlled drugs laws

Today, it's a behemoth.

It not only oversees the police in England and Wales, but MI5, all of the UK's immigration and border apparatus, and a host of bodies responsible for issues ranging from the licensing of bouncers through to the ethics of DNA retention and the use of CCTV cameras.

Every day there could be a civil servant knocking on the home secretary's door from a corner of the department the minister may never have heard of.

2. The Home Office is at the sharp end of some of government's toughest problems

The department's mission boils down to three simple goals for its 31,000 staff:

tackle terrorism

cut crime

control immigration

But the specifics of what is required to meet those objectives are ever-changing, as people who want to do bad things find novel ways to do them.

In the 1980s, for instance, priorities included the fight against the IRA and car crime. Today, the terrorism threat is dominated by jihadist movements that few people fully understand.

Separately, crime is moving online, with billions of pounds being lost every year to tech-savvy fraudsters.

Just last summer, the National Crime Agency said modern-day slavery now affected every town and city and was closely linked to global organised people trafficking,

All these new problems have been emerging in an era that has seen falling spending - leading many critics to say the department's 2010 settlement with the Treasury has added to the likelihood that things will go wrong.

And just when you think it's all change, old problems return.

Just weeks before her resignation, Amber Rudd launched the Home Office's latest attempt to deal with serious violent crime - the sixth such plan in 20 years.

Sometimes, the best laid plans are quickly out of date.

During her time as Home Secretary, Theresa May repeatedly clashed with police leaders

During her Home Office tenure, Theresa May took on the policing establishment and officials pushed through some important changes many said were long overdue.

But there are already calls for more rethinking of the police because of changing demands for their time, such as increasing prioritisation of cybercrimes, domestic violence and sexual offences.

On top of these big strategic questions, the home secretary has to take operational decisions that directly affect national security.

Almost every day, the latest holder of that office, Sajid Javid, will see a secret list of requests from MI5 and some chief constables to bug very (some potentially) dangerous people.

If the minister gets any of these calls wrong, the consequences - either for security or the freedom of someone wrongly accused - could be huge.

3. It's a department where things need to be controlled - but sometimes can't be

The Home Office has a "command and control" culture because so much of its work is aimed at controlling things deemed bad for society. But sometimes things go terribly wrong.

Twelve years ago, the department came as close as it had ever been to being broken up when the then Home Secretary, Charles Clarke, failed to put in place a plan to deport foreign national offenders at the end of their sentences.

Charles Clarke faced intense pressure over his handling of the deportation of foreign prisoners

Quite simply, the prisons arm and the immigration removal arm weren't working together. Charles Clarke was subsequently sacked by then Prime Minister Tony Blair, external, and replaced by John Reid, who would later describe the UK Border Agency as "not fit for purpose".

The immigration system has since gone through a series of major internal changes - and the Home Office gave up prisons to the newly created Ministry of Justice, external. It was meant to make life easier for the home secretary - but time has shown that controlling immigration remains hugely problematic.

The National Audit Office has repeatedly complained that poor Home Office decisions come from poor information.

Nowhere is that more obvious than with the Windrush scandal, or in a string of reports that have criticised other elements of the immigration system.

Some have called for immigration to be given its own ministry. But there's neither appetite for that in Whitehall nor any concrete evidence that it would help.

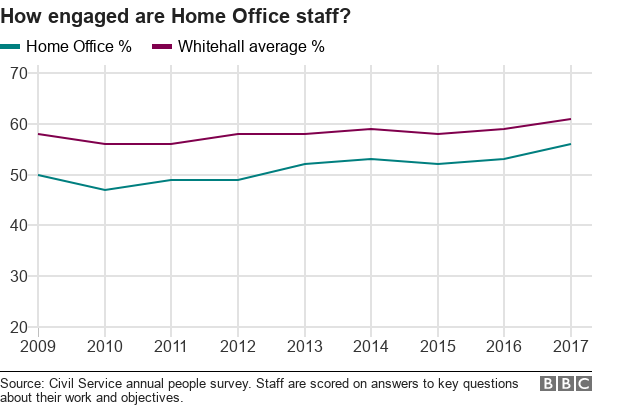

Instead, the department is trying hard to change its internal culture - and one of the biggest challenges it faces is tackling relatively poor staff morale.

Official surveys suggest it's lower than elsewhere in Whitehall - although there has been an improvement since 2016.

4. It's a place where politics and the law regularly come to blows

Every week new threats to take the home secretary to court end up on the desk of government lawyers.

In the past year alone, the department has been defeated in the Supreme Court over its "deport first, appeal later" policy, told that it can't remove EU rough sleepers from the country, and - most recently - ordered to pay punitive damages in a removal case that the Court of Appeal concluded it should never have fought.

Former Prime Minister Tony Blair failed to introduce on-the-spot fines for drunken louts

Sometimes a tough-sounding policy can't be translated into workable law.

Then Prime Minister Tony Blair discovered this 18 years ago when police chiefs and Home Office officials demolished what they thought was an unworkable plan to march drunken louts to cash machines, external to make them pay on-the-spot fines.

Three years ago, then Prime Minister David Cameron promised to ban "extremists", a plan Theresa May also backed, despite critics predicting it would be legally very difficult to deliver. The legislation has yet to materialise.

5. The biggest problems are always yet to come

Nobody has any idea yet how Brexit will affect the department, beyond the simple fact that the Home Office will need to monitor and manage millions more people than before.

But there's still no sign of an immigration bill that will explain the government's objectives after the post-Brexit transition - a situation that Parliament's Home Affairs Committee has described as "unacceptable, external".

Whatever is the next crisis in the making, no matter how bad the Windrush crisis currently looks, the one thing that is certain about the Home Office is that another opportunity to destroy a political career is always just around the corner.

- Published8 May 2018

- Published2 May 2018

- Published30 April 2018

- Published30 April 2018

- Published30 April 2018