Theresa May: Did she solve her seven burning injustices?

- Published

Prime Minister Theresa May said she wanted to "build a better Britain"

When Theresa May became prime minister in July 2016 she promised to build a better Britain and lead a government that worked for everyone rather than being "driven by the interests of the privileged few".

As part of that, she identified seven "burning injustices".

Since the speech, she and the government have been pre-occupied with Brexit - something Mrs May has called "the biggest peacetime challenge any government has faced".

Three years on, the Reality Check team assesses how she has fared in tackling the domestic policy goals she set out in Downing Street.

1) "If you're born poor, you will die on average nine years earlier than others."

In recent years, the gap in life expectancy between the most and least deprived people in England has worsened - by three months for men and seven months for women.

At the time of Mrs May's speech, the most recent figures on life expectancy inequality, external were for 2012-14, and showed a 9.1 and 6.9 year gap for men and women respectively. This had grown to 9.3 years and 7.5 years respectively by 2015-17.

We're looking at England because some key decisions for the rest of the UK, for example around education and health, are devolved to the Welsh, Scottish and Northern Irish governments and are not in Mrs May's power.

Theresa May gave her "burning injustices" speech straight after being asked to form a government by the Queen

Establishing how far Theresa May has acted to address this "burning injustice" is tricky, since life expectancy isn't determined by a single factor.

But there are a few things we know influence how long people are expected to live: lifestyle factors, like smoking and drinking alcohol, and social factors like income, access to good healthcare services and education.

During her premiership, the prime minister pledged an extra £20bn to the NHS in England spread over five years. Globally (with the notable exception of the United States), higher health spending is linked to longer life expectancies.

The benefit of this money hasn't been felt yet, but we could mark this down as an action taken to address this particular injustice in the future.

On the other hand, spending on public health, external - including things like smoking cessation and substance misuse services - has fallen since 2016. Social care didn't get any extra money alongside the NHS's "70th birthday present", and education spending is flat-lining.

Benefits cuts pledged before Mrs May became prime minister have continued to be rolled out and food-bank use and homelessness have continued to rise since the summer of 2016.

Since deprivation is the driver of this inequality in life expectancy, all of these things could play a role longer-term.

2) "If you're black, you're treated more harshly by the criminal justice system than if you're white."

Mrs May has taken steps to make this inequality more transparent, but there has been less in the way of action to directly alter it.

She ordered a Race Disparity Audit, external with the explicit motivation of "tackling burning injustices".

This was designed to show how people of different ethnic backgrounds are treated by a range of public bodies, including the criminal justice system.

It highlighted the fact that, for example, black defendants were more likely than white defendants to be remanded in custody rather than let out on bail while waiting for their cases to go to trial.

These disparities are largely unchanged, and in some cases have worsened.

It's hard to say from this alone that black people are being treated more harshly by the criminal justice system as it doesn't tell us anything about disparities in offending behaviour. But we can also look at the sentences being handed out for the same offences.

Black people were given longer sentences, on average, than white people for the same category of offence in most cases, excluding fraud and criminal damage.

And average custodial sentences for black people have increased over the past couple of years, while for white people they have remained the same.

In June 2016, 42% of under-18s in custody were from a black, external or minority ethnic background, with 22.8% describing themselves as black. By March 2019, the proportion of young people in custody from a minority ethnic, or specifically from a black background, had risen to 49% and 27.8% respectively.

Dr Zubaida Haque, deputy director of race equality think tank the Runnymede Trust, said while the statistics were helpful, "highlighting the gaps doesn't address the gaps".

3) "If you're a white, working-class boy, you're less likely than anybody else in Britain to go to university."

A review into the higher education system, external and its funding is imminent, which could have implications for poorer students.

There's been an upward trend in university participation for many years, and this has continued under Theresa May's supervision.

The number of people going to university for the first time from the neighbourhoods with the lowest higher education participation has increased by 3% since 2016 - a faster rate than the average for all neighbourhoods.

But this is part of a much longer-term trend - it's difficult to point to any of Mrs May's policies that would have particularly driven this.

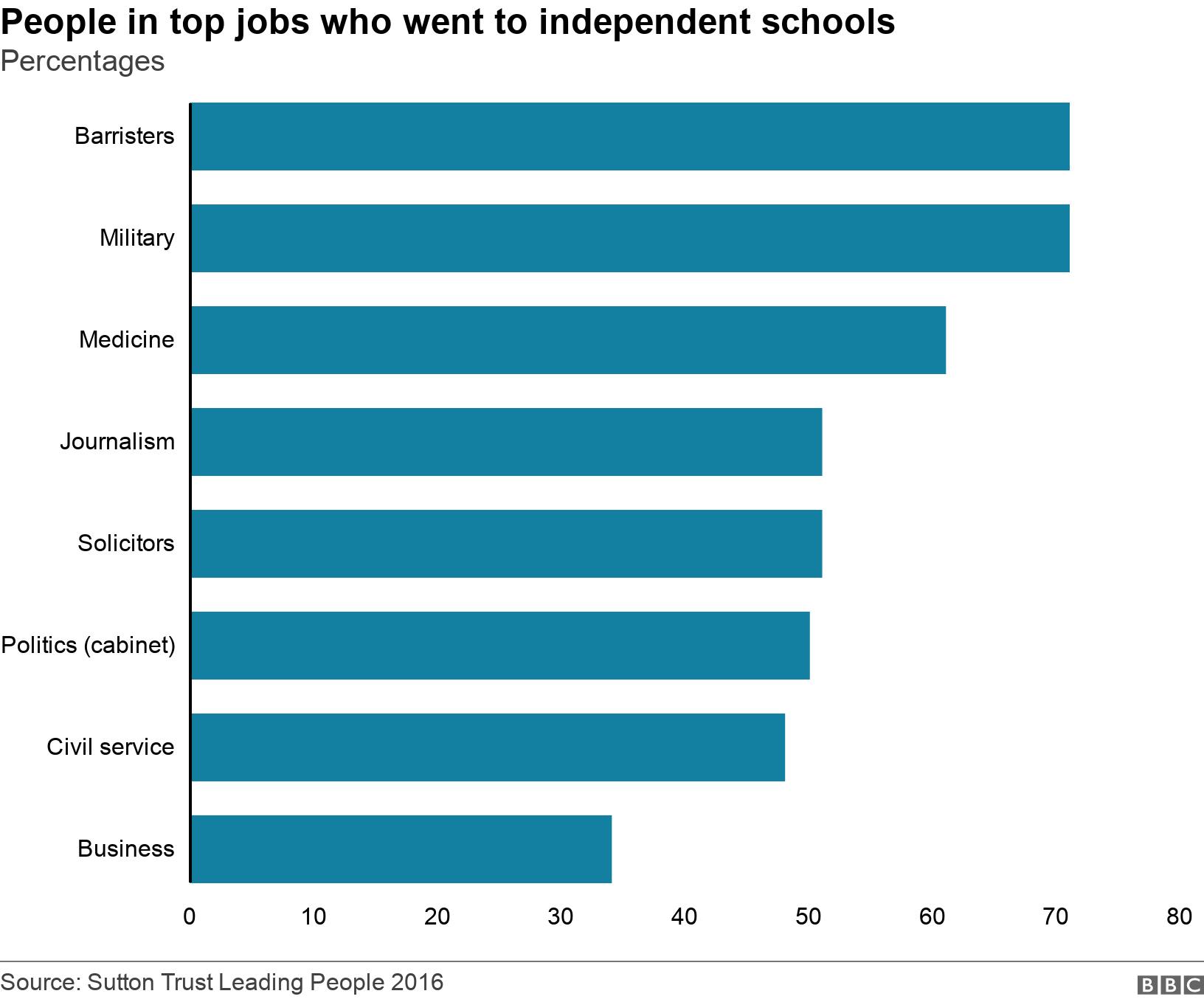

4) "If you're at a state school, you're less likely to reach the top professions than if you're educated privately."

The key data in this area comes from the Sutton Trust, external, which focuses on social mobility. It looked in 2016 at the proportion of people from private schools holding top jobs in a selection of professions.

There is little sign of improvement in this area, although the one area over which Theresa May has direct control - the cabinet - currently has 41% of members who attended independent schools, down from 50% in 2016.

The Social Mobility Commission, which reports to the government on this issue, released its annual report, external in April saying that social mobility had been virtually stagnant for the past four years.

It also found that people from professional backgrounds are 80% more likely to get into a professional job than their less privileged peers.

"At a time when our country needs to be highly productive and able to carve out a new role in a shifting political and economic landscape, we must find a way to maximise the talent of all our citizens, especially those that start the furthest behind," said commission chairwoman Dame Martina Milburn.

But there was some optimism from Russell Hobby, chief executive of Teach First: "Over recent years, we've definitely seen a welcome vigour across the education sector and government when it comes to solving the puzzle of inequality," he said.

"At the government level, this includes a welcome commitment to the pupil premium, new efforts to recruit teachers in poorer areas, and much needed emphasis on careers education in schools."

5) "If you're a woman, you will earn less than a man."

During her time in office, Mrs May extended the duty to report gender pay gaps, external to more companies.

A duty on larger companies to report their pay gaps had already been promised before she took office.

The gender pay gap has continued to narrow since she became prime minister, although this forms part of a longer-term trend.

Women on average still earn 18% less than men.

6) "If you suffer from mental health problems, there's not enough help to hand."

Of the £20bn Mrs May pledged to the NHS, £2bn is earmarked to be spent on mental health.

Despite the investment, there are clear signs services are struggling to cope. The number of out-of-area placements for people needing hospital treatment have risen by a third.

Children's community services are particularly strained. Just 16% of children referred for help last year were seen in six weeks - the rest had to wait longer or were turned away.

The children's commissioner Anne Longfield has said she is worried about the state of these services.

But the NHS's talking therapy programme has continued to grow, with more than a million new starts on a course of therapy in the year ending March 2018, compared with 953,522 in 2015-16. This is largely a culmination of many years of investment in the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies programme, launched in 2006.

Mrs May did take other steps to show her dedication to mental health care.

She appointed the first minister for suicide prevention, launched an annual review of children's mental health in England and ordered an independent review of the Mental Health Act after concerns over the use of force and detention.

7) "If you're young, you'll find it harder than ever before to own your own home."

During her tenure, Mrs May introduced a new stamp duty relief for first-time buyers and an additional £10bn for the Help to Buy loan scheme, both aimed at helping people on to the property ladder.

Home ownership among 25-34 year-olds has fallen steadily over the past two decades as property prices have soared, according to research by think tank the Resolution Foundation - but there's been a small uptick in home ownership among young people since 2016.

The think tank put this in large part down to banks being more willing to offer larger mortgages as post-financial crisis conditions have eased, as well as a slowing in the growth of house prices. But it did also point to stamp duty relief as a factor.

More on May