Brexit: What have been the sticking points?

- Published

A revised Brexit deal, acceptable to both UK and EU negotiators, remains elusive.

Only a few people know exactly what has been discussed behind closed doors, and the legal text of any proposed agreement has not been made public.

But it's worth bearing in mind that most of the deal hammered out by Theresa May's government - the withdrawal agreement and the accompanying political declaration - would remain in place.

The main changes Boris Johnson's government wants to see concern the Irish border, and the type of relationship it wishes the UK to have with the EU in the future.

Customs

All sides have ruled out customs checks at the land border in Ireland (between Northern Ireland and the Republic), and Mr Johnson's suggestion that checks could take place at "designated locations" away from the border was rejected by the EU.

That means there would have to be some customs checks within the UK instead, at ports along the Irish Sea between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. That's a big UK concession.

But Mr Johnson also insists that Northern Ireland has to leave the EU customs union, along with the rest of the UK, to allow it to take advantage of any future trade deals the government manages to negotiate.

The suggested compromise is that the legal customs border between the UK and the EU would be at the land border in Ireland. But the practical border, where checks would actually take place, would be in the Irish Sea.

Diplomats say that means Northern Ireland would remain legally in the UK customs territory but it would apply EU customs processes on goods arriving from Great Britain. There would be exemptions, including on personal items and other goods, to be agreed at a later date by the UK and the EU.

So it's a dual customs system, which has no obvious parallel anywhere else in the world, and it raises plenty of technical and legal issues which will take some time to pin down.

Consent

There's also the issue of political consent in Northern Ireland.

Both sides agree that any new economic status for Northern Ireland, which sets it apart from the rest of the country, needs to win democratic approval.

But the EU won't accept anything that appears to give a veto to one party in Northern Ireland, in this case the government's allies in the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). That, in the EU's view, would mean the entire proposed settlement on the Irish border could be unexpectedly torn up with nothing to replace it.

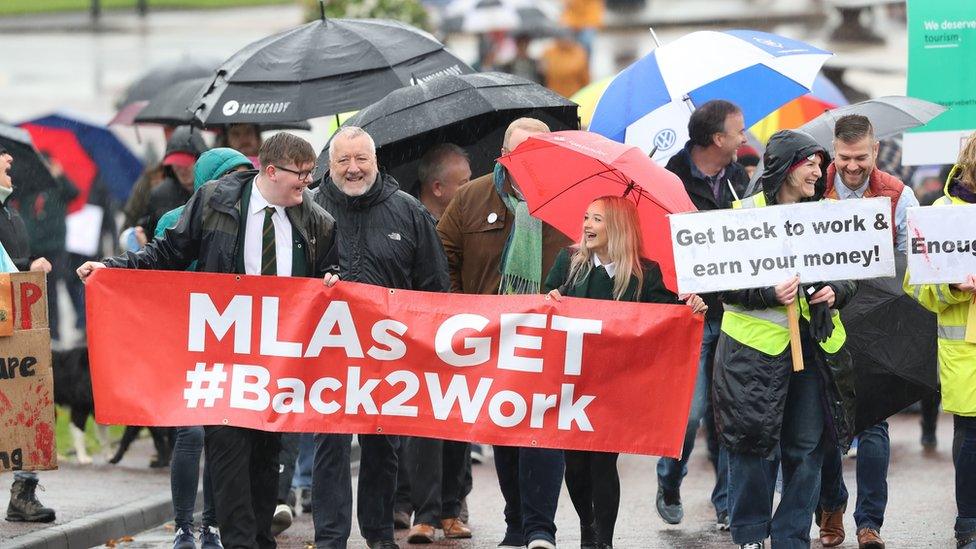

The Northern Ireland Assembly has not been sitting for more than 1,000 days

For its part, the DUP has been arguing that the Good Friday agreement, which forms the basis of the Northern Ireland peace process, provides for a dual majority (in other words a majority among both unionist and nationalist representatives) on controversial issues in the Northern Ireland assembly.

Others in Northern Ireland argue that if a dual majority is needed, then the prospect of Northern Ireland leaving the EU should also be subject to similar dual consent.

Diplomats say the latest draft agreement outlines a plan which would give the Northern Ireland Assembly a consent vote four years after the Brexit transition period ends in 2020.

If it voted to continue the new arrangements by a simple majority, another vote would be held four years later. If the vote was carried with a dual majority it would be held again eight years later.

Diplomats say that if the Assembly voted to end the arrangements, the UK and the EU would have two years to negotiate a new method to avoid a hard border.

All of this would replace the so-called backstop - the proposed guarantee to avoid a hard border in Ireland under all circumstances.

But so far, the DUP has made it pretty clear that it cannot accept the proposals as they stand.

Future Relations

The UK has submitted a new draft of the political declaration on the future relationship. Again, the text has not been made public, but Mr Johnson has made it clear that he wants a looser economic relationship with the EU in the future than Mrs May was seeking.

Diplomats say the political declaration will point towards a free trade agreement between the UK and the EU with zero tariffs or quotas, but one which is embedded in a framework for economic competition that is "fair".

One of the key phrases to watch out for here is the "level playing field" - the degree to which the UK will agree to stick closely to EU regulations on things like social and environmental policies.

Mr Johnson wants to make fewer level playing field guarantees, and the EU fears that could mean he will seek to undercut EU regulation in the future to gain a competitive advantage.

And that in turn has made a number of EU countries even more determined that any solution for the Irish border is legally watertight and fully thought through, before they sign up to any amended Brexit deal.

VAT

In any complex negotiation, there is nearly always an issue bubbling under the surface which emerges as a last-minute hitch.

This time it is VAT, and how to prevent fraud involving goods crossing any new border arrangement.

Time

On all of these issues, time is against the negotiators and their political masters. Mr Johnson still says he is determined to leave the EU on 31 October.

But if the House of Commons has not voted in favour either of a deal or of leaving with no deal by 19 October, then UK law says he must seek an extension to the Brexit process.

The EU has said it will not negotiate directly with Mr Johnson during the summit, which begins on Thursday.

But the next few days are obviously crucial.

Brexit explained

Brexit - British exit - refers to the UK leaving the EU. A public vote was held in June 2016, to decide whether the UK should leave or remain.