David Cameron: EU referendum claim fact-checked

- Published

Former Prime Minister David Cameron was asked on BBC Radio 4's Today programme whether he had any regrets about calling the 2016 referendum and whether he did it for "party management reasons"?

Mr Cameron said "every party was under pressure on this issue... every single political party in Britain fought an election between 2005 and 2015 with a pledge to hold a referendum: the Labour party did, the Liberal Democrats did, the Greens did, UKIP of course did, we did."

Is he right?

What did the parties say?

Not every party consistently argued for a straightforward in/out referendum, with the option of leaving the EU altogether, in that time.

But it's true to say that membership of the EU as an issue for political parties pre-dated 2014.

That was the year that the UK Independence Party (UKIP) won the most votes in the European Parliamentary elections, sweeping away their far more established competitors.

"I've read so many times… that the referendum came about because the Tories got whacked by UKIP in the 2014 elections," Mr Cameron said.

But he denied this, saying that support for a referendum "wasn't a flash in the pan".

The Liberal Democrats, although staunchly opposed to the UK leaving the EU, were the first major political party to call for an in/out referendum.

Current leader of the party Jo Swinson said in Parliament in 2008 that the Liberal Democrats "would like to have a referendum on the major issue of whether we are in or out of Europe".

An official party leaflet from around this time also supported the idea.

The party's 2010 election manifesto said it remained committed to an in/out referendum "the next time a British government signs up for a fundamental change in the relationship" with the EU.

This wasn't an indication of the party wanting to leave - it said it still believed it was in Britain's long-term interests to join the euro - but it did say there were circumstances in which the terms of membership should be put to the people of Britain.

Similarly, the Green Party in 2010 supported proposals for an in/out referendum, saying: "It's yes to Europe, yes to reform of the EU but also yes to a referendum".

Labour supported a referendum on the terms of the UK's membership in its 2005 manifesto - although not a straightforward choice between leaving or remaining. It dropped this pledge in 2010.

Mr Cameron and his successor Theresa May

Once a referendum had already been pledged by the Conservatives, in the 2015 election Labour stood on a manifesto of guaranteeing that there could be "no transfer of powers from Britain to the European Union without the consent of the British public through an in/out referendum".

As for the Conservative Party, it formally pledged an in/out referendum - with a time limit to deliver it - in 2015. The party had called for referendums on accepting elements of the EU constitution and on further transfers of power in 2005 and 2010.

In 2011, the coalition government established a so-called "referendum lock", creating a legal requirement to hold a referendum if any proposal were made to transfer further powers from the UK to the EU.

At a speech in 2013, Mr Cameron first suggested that he planned to hold a referendum in due course. He argued against holding an in-out referendum at that point, but said there should be time for a "proper, reasoned debated".

"At the end of that debate you, the British people, will decide," he said.

He indicated that he was in favour of remaining in a reformed EU.

What did the public think?

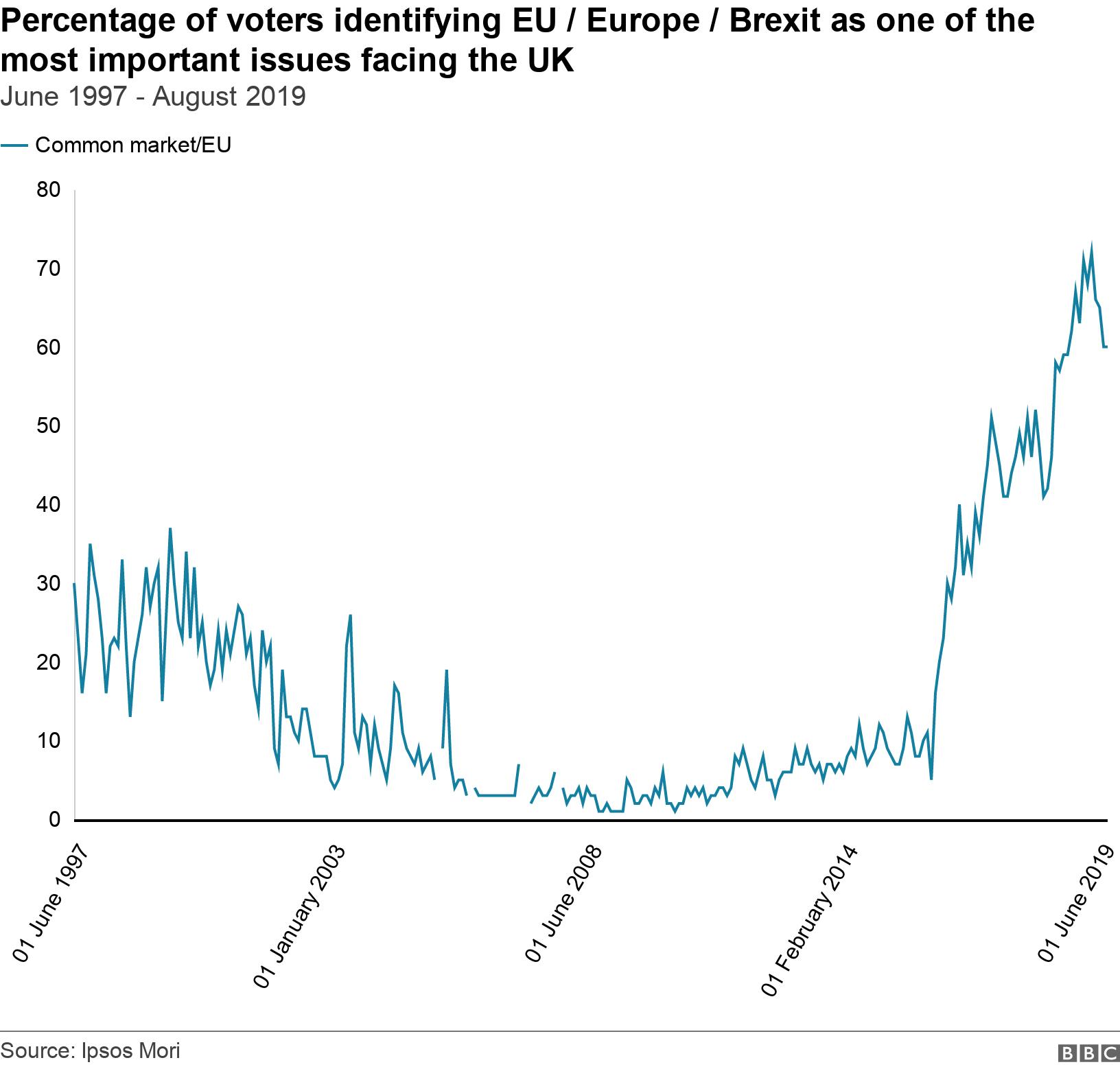

Since 1997, polling company Ipsos Mori has asked about 1,000 British voters every month which issues are the most important facing the country.

In the years leading up the 2016 referendum, Ipsos Mori's data shows Europe initially featured very low down on the public's list of concerns.

Soon after Mr Cameron became PM in 2010, for example, only 1% of British voters listed Europe as an important issue.

Despite the issue trending upwards in the years that followed, only 8% identified Europe as a concern in May 2014 - the month of the European elections.

But this seemingly low score may not tell the whole story.

While the economy dominated voters' minds in the early 2010s, immigration was also a significant and rising concern.

Michael Clemence, from Ipsos Mori, says that the two issues of Europe and immigration are likely to have been conflated as one in the minds of some voters around this time:

"Public concern about the EU (and what would later be called Brexit) stays pretty low until after the referendum vote in 2016."

"However, in the years prior to the referendum, concern about related issues was higher. For instance, immigration was the biggest worry for the British public in both 2014 and 2015," he says.