Profumo scandal evidence still secret in 'cover-up'

- Published

Cabinet minister John Profumo was forced to resign after he lied to Parliament

A former member of a government advisory panel on historical records says he has "never experienced such a concerted effort to withhold papers" as happened with the still secret files of the Denning inquiry into the Profumo scandal.

The art historian and TV presenter Bendor Grosvenor, who served for seven years on the Advisory Council on National Records and Archives (ACNRA), external, says: "It was hard to escape the conclusion there was something of a cover-up going on."

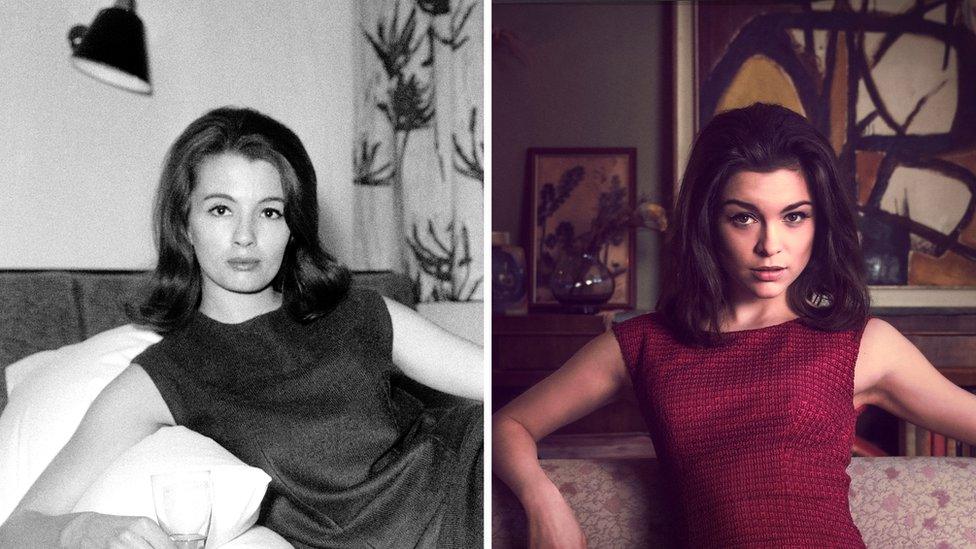

The recent BBC drama about the events surrounding Christine Keeler has drawn new attention to the continuing official secrecy regarding the Profumo affair of the early 1960s, which gripped the nation and shook the government.

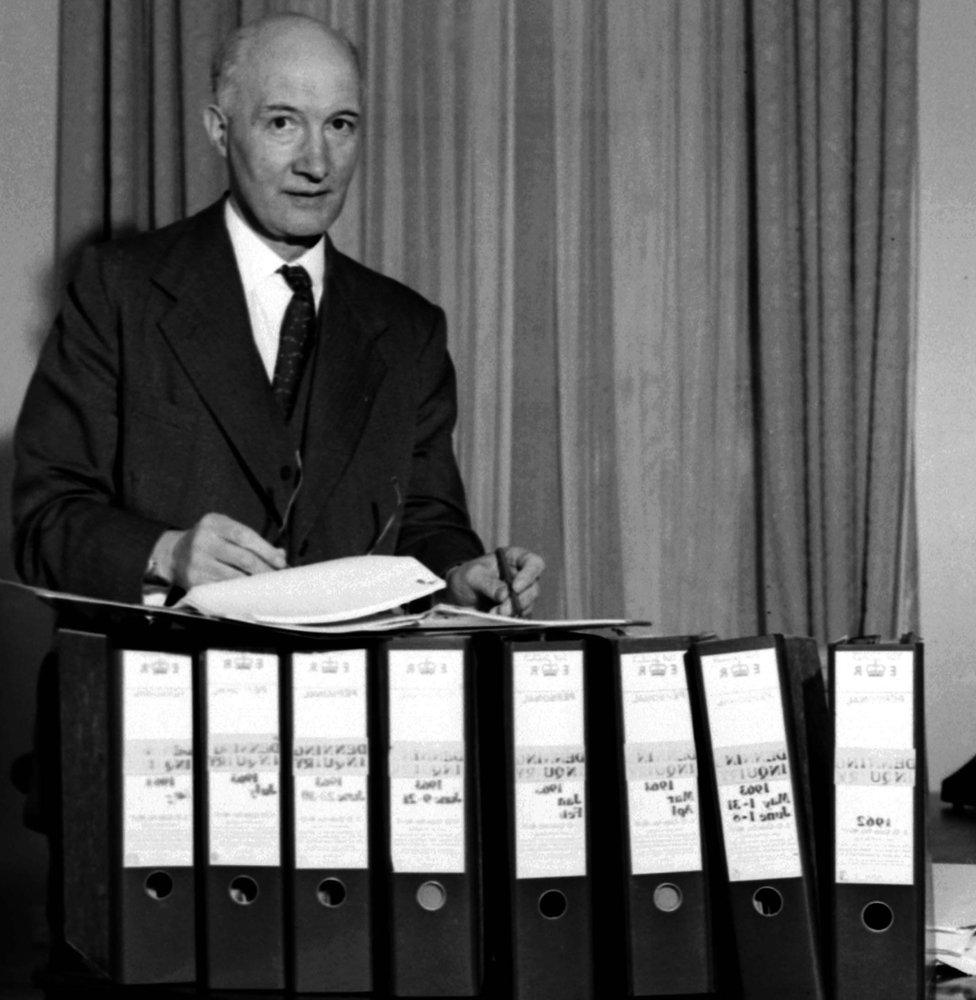

The files from the official judicial inquiry by Master of the Rolls Lord Denning have not yet been publicly released.

The Cabinet Office spent two years in discussion with the ACNRA, which gives advice on which historical papers should be released or stay secret, resulting in a decision to keep the files confidential until 2048.

According to ACNRA documents obtained by the BBC under freedom of information (FOI), the identity of some who gave evidence to Lord Denning has "never been known to the public". Some of these unnamed people were still alive in 2014 and possibly still are.

It raises questions as to how far the reaches of the scandal stretched into the British establishment.

John Profumo was forced to resign as Secretary of State for War in 1963 after he admitted lying to the Commons when he denied any "impropriety" with a young model, Christine Keeler. It turned out he was having an affair with her, while she also had a relationship with the Soviet naval attaché in London, a presumed spy.

While this presented an obvious security issue, tabloid newspapers at the time also featured sensational rumours that it was just one aspect of mysterious sexual scandals in high-class circles.

Appointed to conduct a judicial inquiry, Lord Denning concluded, external there had been no security breach and there was no evidence to link ministers to certain stories of "vile and revolting" sexual activities. His report has since been widely criticised as complacent.

Lord Denning's inquiry files are still secret

The judge omitted from his published report testimony from a prostitute who said, external transport minister Ernest Marples - who died in 1978 - had paid her to beat him while he wore women's clothes.

In 2015 the Cabinet Office reluctantly agreed with the ACNRA to transfer 25 boxes of Denning inquiry files for safekeeping to the National Archives. Of these, 23 were to be kept closed to the public until 2048 (the other two contained material already in the public domain, such as press cuttings).

According to minutes of advisory council meetings obtained by the BBC under FOI, the Cabinet Office initially asserted the papers were too sensitive to be taken away from its own direct control. It maintained some of the material affected national security.

In later discussions the Cabinet Office argued it was necessary to preserve the confidentiality of the judicial inquiry and protect personal information.

Dr Grosvenor says: "I was suspicious as the arguments to protect the papers kept changing."

"The papers should absolutely be made available to the public," he adds. "We fought off some rather spurious arguments. But by the end of it everyone felt rather worn down by the Cabinet Office."

The suggestion of releasing redacted records was dismissed on the basis, according to the minutes, that the amount of editing needed "would have left an unintelligible mess, and the release of snippets of information could cause an adverse public reaction".

Lord Denning had assured inquiry witnesses that their evidence would be confidential and only used for the purpose of his report. He also wanted all the transcripts and statements to be destroyed afterwards, but this wish was not carried out by civil servants.

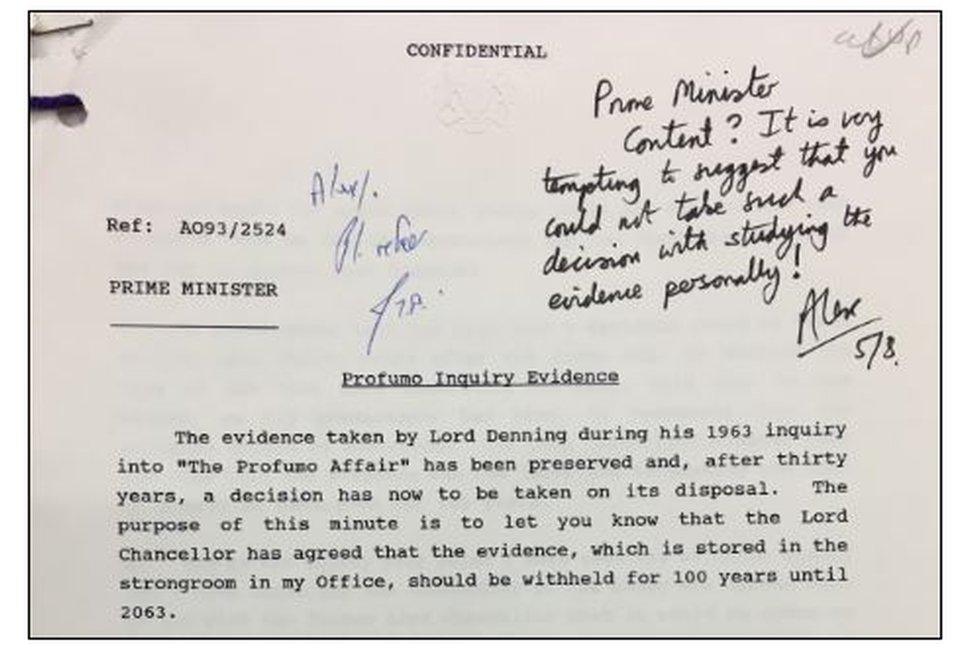

Reviewing the papers 30 years later in 1993, Cabinet Secretary Sir Robin Butler said it would be wrong to destroy them, as "they reflect an extraordinary episode and evoke the character of the 1960s in a very powerful way" and "historians would judge us harshly for such destruction". But he argued they should still be kept secret for several decades.

Another official then wrote to the then Prime Minister John Major: "It is very tempting to suggest that you could not take such a decision with (sic) studying the evidence personally."

Whether or not he took advantage of this opportunity, it will not be available to historians or members of the general public for many years to come.

The National Archives has dismissed a recent BBC FOI request for Denning inquiry evidence on the grounds that even if witnesses themselves are now dead, "the highly personal nature of the information" could "cause damage and distress to their families". The FOI refusal was upheld by the Information Commissioner.

A Cabinet Office spokesperson said: "The National Archives' Advisory Council recommended that the Denning inquiry records continue to remain closed until 1 January 2048. As with any historical records we follow procedures and guidance from the National Archives."

An Advisory Council spokesperson said: "The Advisory Council discussed the status of papers relating to Lord Denning's inquiry into the Profumo affair with the Cabinet Office over a period of time from 2014 to 2016. The papers were subsequently transferred to the National Archives closed under exemptions of the Freedom of Information Act."

- Published30 December 2019

- Published5 December 2017