Boris Johnson: The prime minister's year in No 10

- Published

It is one year since Boris Johnson became the prime minister of the UK.

And it wasn't 12 months he - or any of us - could easily forget.

On the anniversary of his premiership, we take a look at some of the most defining and controversial moments so far.

Getting Brexit Done

The country was following every twist and turn, watching Brexit votes and key decisions unfold in Parliament.

But when Mr Johnson came to power on 24 July 2019, his first task was getting to grips with Brexit - and following through with his plan, to ditch his predecessor Theresa May's deal and renegotiate with Brussels.

All sides of the Brexit argument took to the streets

When he took the reins, the deadline for leaving the EU was 31 October, and he condemned the "the doubters, the doomsters, the gloomsters" who didn't think an agreement was possible by then.

But protesters for both Leave and Remain swarmed around the House of Commons, he barely had a majority in Parliament and there were more rebels on his benches than John Bercow's daily "order!" tally.

Boris Johnson: "I'd rather be dead in a ditch" than ask for Brexit delay

Mr Johnson managed to secure a new deal with the bloc - minus the Irish backstop.

But it took withdrawing the whip from 21 of his own MPs, multiple failed votes in the Commons, an unsuccessful Saturday sitting, having to request an extension he'd rather "die in a ditch" than ask for, and, eventually, an election to get it passed.

The UK left the EU on 31 January and in March, the trade negotiations between the two sides began, with another deadline of the end of the year to contend with.

The unlawful prorogation

As if there wasn't enough argument amongst MPs, the PM set off more fireworks early on in his tenure.

While Westminster was on its summer break in August, Mr Johnson announced he planned to prorogue Parliament within days of its return in September until 14 October.

Some MPs voiced their objection to the suspension in the Commons

He said it would allow him to come back with a Queen's Speech and outline his "very exciting agenda" as the new man at No 10.

But MPs criticised the lengthy closure, accusing him of avoiding scrutiny, knowing it would only give them two weeks to pass proposed legislation preventing a no-deal Brexit.

Rows broke out, the Speaker got involved, and eventually the whole decision ended up in the Supreme Court, leading to Lady Hale ruling Mr Johnson's action as "unlawful".

Protesters rallied in Parliament Square against the prorogation

MPs came back to the Commons and got their no-deal blocking law, but Mr Johnson also got his Queen's Speech, with his plans laid for his time in Downing Street.

Who would have thought another Queen's Speech was only two months away...

Winter election

Another issue which cropped up throughout the first few months of Mr Johnson's leadership was when he would call an election.

The Tory majority was slim, and in order to achieve his plans, he would need the backing of the Commons.

The numbers in the Commons were not in the PM's favour before the election

But with prominent rebels scattered over his benches and a failing partnership with the DUP, it seemed impossible to garner support.

Within days of getting the keys to No 10, Mr Johnson ruled out a pre-Brexit election, saying voters wanted him to "deliver on their mandate" to exit the EU, not head back to the polls.

But failing to get his newly-negotiated deal through led to a change in approach from the PM.

He took to the dispatch box three times to call for an election. But under the Fixed Term Parliament Act, he needed two thirds of the Commons to agree.

On the fourth attempt, having written to the EU to ask for an extension to the Brexit deadline, he got what he wanted and an election date was set for 12 December - the first December election since 1923.

Boris Johnson introduced his campaign slogan in a novel way

Five weeks of campaigning began and the parties' policies were announced: the Tory's mantra of "Get Brexit Done" vied with Jeremy Corbyn's Labour calling to renegotiate the deal under their leadership - before putting it to a confirmatory referendum - and the Liberal Democrats promising to revoke the decision to leave the bloc altogether.

Cue head-to-head debates, cheering (and booing) crowds, and at one point, even a JCB digger being driven through a wall.

But on the night, Mr Johnson came home with a huge - by recent standards - 80-strong majority, securing his spot as prime minister, heralding the end of Jeremy Corbyn's leadership of the Labour party, and the end of the UK's membership of the EU.

Coronavirus

While much of the prime minister's first six months were dominated - as expected - by Brexit, he, the country, and the world, were in for a shock.

A few cases of Covid-19 had made their way into the UK in early 2020, but by March, Mr Johnson was addressing the nation, telling them to stay at home, protect the NHS and save lives.

Boris Johnson: "You must stay at home"

He came in for some criticism for not locking down the country earlier - and for some poorly chosen words on shaking people's hands - but everything changed when, within days of the announcement, the PM himself tested positive for the virus.

Soon Mr Johnson was in hospital, and subsequently was moved into intensive care. He began to recover and was moved out of the ICU.

And after a few weeks recuperating at Chequers, he was back in the hot seat in Downing Street, relieving his stand-in, Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab.

The PM was isolating and working from home after he tested positive for coronavirus

Back in charge, Mr Johnson faced questions over his decisions in tackling the outbreak.

There may have been praise for the establishment of the Nightingale hospitals, the sourcing of ventilators and the introduction of a furlough scheme for workers.

But there was criticism too - over failed testing targets, strategies for care homes and missing supplies of PPE.

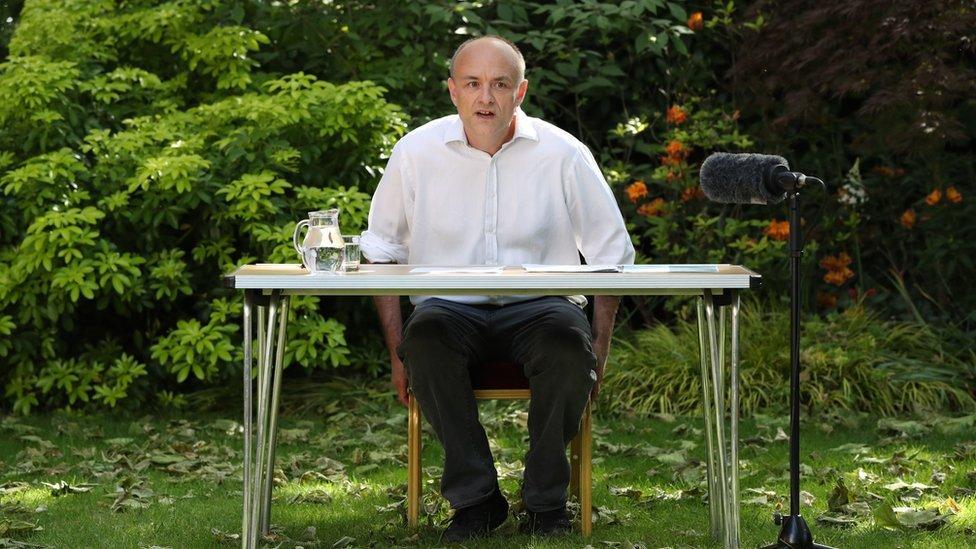

Criticism too, for Mr Johnson's decision to stand by his top aide, Dominic Cummings.

Dominic Cummings gave a press conference to explain his trip to County Durham during lockdown

Mr Cummings was widely criticised for travelling to County Durham from London at the height of the pandemic while he and his wife had the virus.

Lockdown measures may be easing, but coronavirus will dominate politics for the foreseeable future.

Hot topics

While coronavirus has, understandably, been the leading issue in Westminster and beyond in recent months, it has not been the only problem on Mr Johnson's desk.

Back in February, the prime minister was accused of "hiding" when severe flooding hit several parts of the UK, and action had to be taken to help struggling communities.

The PM had some awkward encounters when he visited flood affected areas

HS2 also became another hot potato for the PM, as he decided to back the project despite dismay from some in his own party.

And the issue of Chinese telecoms firm Huawei heated up debate within Conservative circles again.

Mr Johnson gave the green light to using the company's equipment in the UK's future 5G network back in January, albeit with limited market share.

But this was not enough for some vocal backbenchers, and eventually there was a change of tack by the PM.

The UK has now ruled out buying any of the firm's equipment for the network after the end of this year and is forcing mobile providers to remove all of its 5G kit from their networks by 2027.

The decision around Huawei has been a major test for Boris Johnson

There have also been rumblings about Mr Cummings and his plans to shake up Whitehall, after a number of senior civil servants announced they would step down from their roles this year.

Four figures have announced their exit in six months, and the most senior, Cabinet Secretary Sir Mark Sedwill, saw his role split, as he was replaced as national security advisor by a political appointee, chief Brexit negotiator David Frost.

The most recent controversy, of course, is the release of the Intelligence and Security Committee's report into Russian influence in the UK.

Boris Johnson was accused of holding up the report on Russian interference

The report claimed the UK was "playing catch-up" in face of the threat and had not investigated alleged interference in the 2016 EU referendum.

Mr Johnson was accused of sitting on the report for months and preventing its release ahead of the general election - as well as coming under fire for kicking the committee's new chair out of the parliamentary Tory party after he won the position ahead of No 10's alleged preferred candidate, Chris Grayling.

But the PM has dismissed the accusations, promising to update security laws and tackle the Russia threat head on.

The personal

It wasn't just political storylines that dominated the last year for Boris Johnson.

When he moved into No 10 last July, he was accompanied by his girlfriend Carrie Symonds, making them the first unmarried couple to ever live at the famous address.

The couple were pictured together at the Tory Party conference

Mr Johnson and his second wife, Marina Wheeler, had announced their split in September 2018 and were in the process of getting a divorce when he became leader.

The pair got their first pet together, a dog called Dilyn.

Boris Johnson and Dilyn pose for pictures together

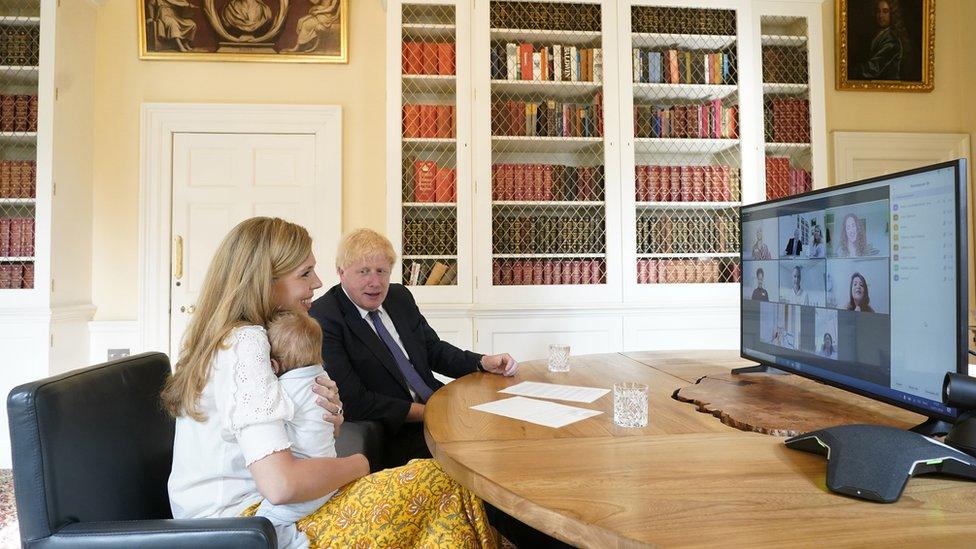

But come February, the couple announced they were engaged and Ms Symonds was expecting their first child.

At the start of May, Wilfred Lawrie Nicholas was born, named after their grandfathers and two doctors who treated Mr Johnson while he was in hospital with coronavirus.

Soon after the birth, Mr Johnson and Ms Wheeler's divorce was finalised.

The couple took part in a video call with midwives after the birth of their son

The PM also faced questions about his relationship with another woman, US businesswoman Jennifer Arcuri.

There were accusations she had received special treatment from him while he was Mayor of London and that the pair's relationship went beyond that of friends.

However, Mr Johnson denied the claims and said everything was done "entirely in the proper way".

More to come

Remember, under the Fixed Term Parliament Act, Mr Johnson has five years in charge of No 10 - unless two thirds of the Commons votes for an election.

As he has said, "we are not out of the woods yet", when it comes to coronavirus, and he has confirmed there will be an inquiry.

The economy has taken a massive hit, and questions keep on coming about how all the extra borrowing his government has undertaken will be paid back.

And, on top of this, post-Brexit trade talks with the EU are ongoing.

There will be plenty more action in Downing Street for Boris Johnson

So, watch this space for more drama in Boris Johnson's tenure.