Are judges about to be neutered?

- Published

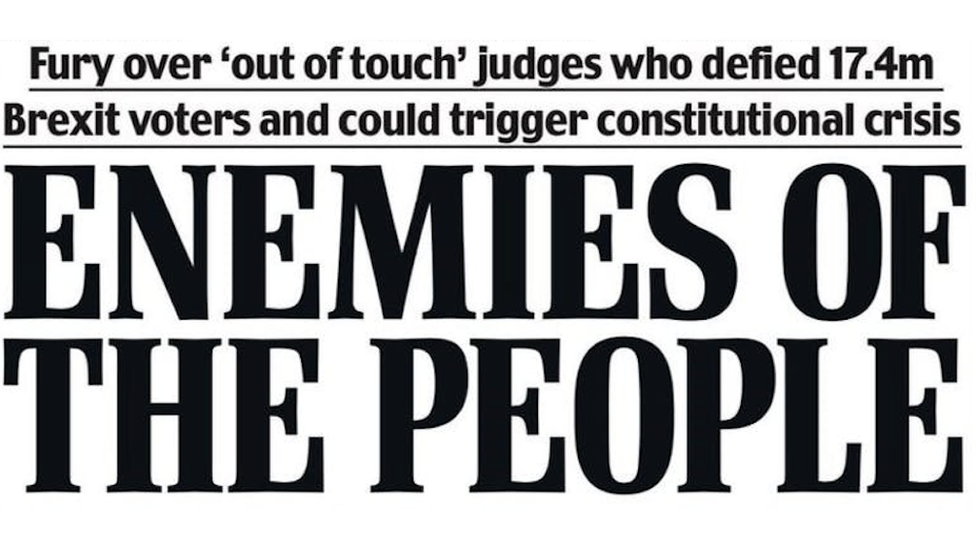

The Daily Mail's thundering headline attacking judges in the first Brexit case

It arguably became an issue in the public's mind with a headline: Enemies of the People.

So wrote the Daily Mail about judges who said only Parliament could trigger Brexit, rather than the prime minister.

Five years on, and the government plans to change Judicial Review (JR) - the tool behind that decision - and one of the most important features of the legal landscape.

Supporters of the plan to reform JR say its essential to prevent the courts being clogged up with meritless cases - and to stop judges taking political decisions.

But opponents say those claims don't stack up - and believe a significant act of constitutional reform is being driven by political revenge.

What is Judicial Review?

A Judicial Review is a High Court case in which someone asks a judge to examine whether a minister, official or public body broke the law in how they took a decision

It's not new - and every modern democracy has a comparable tool

The most famous British JR is the Supreme Court's ruling that Boris Johnson unlawfully shut down Parliament amid the Brexit political crisis

Most JRs go unnoticed - but they play a crucial role in good governance for many ordinary people who feel they have been wronged - people like Lucy Burke

Why Lucy turned to the law

Lucy and her son Danny

Lucy Burke's 20-year-old son Danny is a keen weight-lifter and talented skier. He also has autism and a learning disability so he needs help with a range of everyday things.

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence issued guidance that meant people like Danny could be denied critical care if hospitals were overwhelmed during the pandemic.

"That was absolutely terrifying," said Lucy. "Danny lives with something which is a stable lifelong difference, but the idea his dependence on others would be used in a critical care situation was really concerning. Nobody had stopped to think about that."

And so Lucy began a JR, warning Nice it would end up in court unless it thought again.

It's worth noting that her case is very similar to most of the 4,000 JRs every year - a simple concern of an injustice, that a court is being asked to examine.

Why are JRs controversial?

Only about 5% of JR claims ever reach court and less than half are successful, as detailed in the independent review of the power, external, commissioned by the government.

The most famous of Judicial Reviews: The Supreme court's ruling that Boris Johnson had unlawfully shut down Parliament

Critics claim many JRs have grown out of control and have led judges into politics, as their courtrooms are used to fight policy battles that should be left to Parliament.

The right-leaning think tank Policy Exchange - which has championed reforming JR - has listed some of these controversies, external.

While JRs have grown in use over the last 70 years, that seems to be because there are more state agencies with legal powers that the courts need to inevitably oversee.

And the government's hand-picked independent panel concluded that, in general, judges are not overstepping the mark.

However, the government has decided to press on with reforms in a bill now before Parliament.

Lord Chancellor Robert Buckland - the minister in charge of the legal system - proposes:

Creating a new way for judges to delay when the government has to act on a defeat in the courts, to give it more time to respond

Allowing judges to rule that while the government has broken the law, it does not need to do anything to retrospectively fix the mistake

Banning a specific form of last-ditch appeal in immigration cases, known as "Cart JRs"

The most interesting thing is what's hidden in the legal weeds. The government's independent review rejected a repeatedly-floated idea to exclude entire classes of ministerial decisions from court scrutiny.

These so-called "ouster clauses" could, for example, be created to prevent courts examining how a prime minister shuts down Parliament.

That explicit proposal is not in the bill - but the Ministry of Justice says the wording to outlaw Cart JRs could be a "template" to create more ouster clauses in the future. So the idea is not quite dead - and the final wording passed by Parliament may dictate whether ministers get an opportunity to have another go by a back door.

Is tension between judges and ministers new?

Sir Jonathan Jones QC was until last year the Treasury Solicitor - the head of government's elite in-house lawyers who spend their days defending judicial review claims.

His teams advise decision-makers how to act within the law - there's even a comprehensive guide to JR-proofing policy-making, which is a blueprint to good government, external.

He says during his career he saw no evidence judges were taking political decisions - but identifying legally bad ones when presented with the evidence.

"The truth is that the government wins most cases," says Sir Jonathan. "When it doesn't, there is normally a good reason why. It's not because the judges are just going off on one."

He argues that governments of all colours get frustrated with the courts as they find it harder to get things done as quickly as their manifesto had suggested.

"History has shown that ouster clauses don't work," says Sir Jonathan. "In the end, who's going to tell you where the limits of the law are, if it's not the courts?"

Algorithm exam grades: Controversial Covid plan was targeted by a JR until the government abandoned it

Professor Richard Ekins of the University of Oxford and head of Policy Exchange's Judicial Review has however urged the government to go further to correct the legal and political balance.

"The Judicial Review and Courts Bill is a welcome first step in the wider project of restoring the UK's traditional political constitution and vindicating the rule of law," he says.

"It has always been open to Parliament to reverse judgments of our highest courts and the Bill's measures are a carefully considered, limited response.

"This Bill is thus a narrowly framed proposal, which should be the beginning but not the end of the reform process."

Some significant recent judicial reviews:

2020: Students threatened to JR the controversial Covid A-Level algorithm. The Department for Education scrapped it rather than go to court

2018: The High Court ruled that the Parole Board had acted irrationally in deciding to release serial "Black Cab" rapist John Worboys

2017: The Supreme Court ruled in favour of a judicial review that said a controversial fee for access to the Employment Tribunal was unlawful - which had prevented people who had been treated unfairly from taking their boss to court

The Public Law Project could not disagree more. The campaign group's director Jo Hickman argues it's still difficult to understand what the government is trying to fix.

It asked the statistics watchdog to look at the figures used by the government to justify banning Cart JRs as a waste of time and money. The regulator concluded the government's case was indeed over simplistic, external.

"Throughout this process, the evidence to substantiate proposals has been either non-existent, misleading, or consistently hidden from view," says Ms Hickman.

"Not being able to undo the past consequences of an unlawful decision could undermine the point of having a legal mechanism that holds public authorities to account. This could plainly lead to some very unjust outcomes."

What happened to Lucy Burke's case?

Which brings me back to Lucy Burke and her son Danny who challenged the National Institute for Clinical Excellence's Covid guidance.

When the agency received her JR threat, it was enough of a cocked legal pistol to make it scrap and rewrite its critical care guidance there and then.

And that is how many JRs actually end - with a decision revised long before the matter gets into court.

"Judicial review is so important," says Lucy. "I was really glad that it was resolved early, but I would have been prepared to pursue it had it not been. How else will ordinary people challenge decisions by big powerful entities?"