What is the Private Members' Bill ballot?

- Published

The late Dame Cheryl Gillan made her Autism Act law through the Private Members Bill ballot

A little after 09:00 BST (08:00 GMT) on Thursday, a handful of MPs will - quite randomly - become very popular.

Seven of them will have won guaranteed debating time for a proposed new law of their choice in an annual "ballot" - a kind of parliamentary prize draw, presided over by the senior deputy speaker of the House, Dame Eleanor Laing.

As a result, they will become every lobbyist and pressure group's new best friend.

A further 13 MPs will have some chance - but not a guarantee - of getting their proposals debated, and they too will be able to bask in unaccustomed attention, although not to quite the same degree.

But all will enter into the parliamentary game of snakes and ladders that is the Private Members' Bill process.

They will climb the ladder of parliamentary fame by promoting some important cause, with media appearances and op-ed articles in the national press.

Then they will slide down some procedural snake as opponents drone away their debating time or allies fail to turn up to force their bill through.

Unwinnable or feasible?

Top of the ballot last time around was Labour MP Mike Amesbury, who steered through a measure to stop schools from requiring their pupils to wear expensive branded uniforms - a cause backed across the House.

He set his sights on an achievable goal, built alliances and worked with ministers and other parties to secure a change in the law that he thought would benefit his constituents.

And that is one of the big choices that confront winners of the annual ballot - should they take on some high profile but probably unwinnable cause, or find a feasible change in the law to aim for?

Big is not necessarily unfeasible, and unfeasible does not always mean ineffectual.

Past Private Members Bills have legalised abortion (David Steel), homosexuality (Leo Abse) and secured the abolition of the death penalty (Sydney Silverman).

More recently, there have been highly significant reforms from the late Cheryl Gillan (the Autism Act) and from Bob Blackman (the Homelessness Reduction Act).

And in the Blair years, the Labour MP Mike Foster failed to get through a bill to ban hunting with hounds, but the level of support he attracted on his own benches forced the government to legislate.

The ban on fox hunting came about after pressure from a Private Members Bill

Quite deliberately, the bills are very vulnerable creatures, which can be killed off by determined minority resistance.

Unlike government bills, debates on them are not timetabled so that a vote is taken at a set time - and speeches are not time-limited either.

That means that a few determined opponents can just keep talking, run down the clock and prevent a bill coming to a vote until the day ends - at which point the bill in question goes to the back of the queue and, usually, is never seen again.

It is known in the trade as a filibuster, and the art of filibustering is actually quite skilled.

Practitioners can't just drone on - they must have something substantive to say about the bill they're debating and they must avoid deviation, hesitation or repetition (although smart filibusterers can sometimes get away with repeating sections of their speech if the deputy speaker in the chair changes and the newcomer hasn't heard the earlier part of what they've been saying).

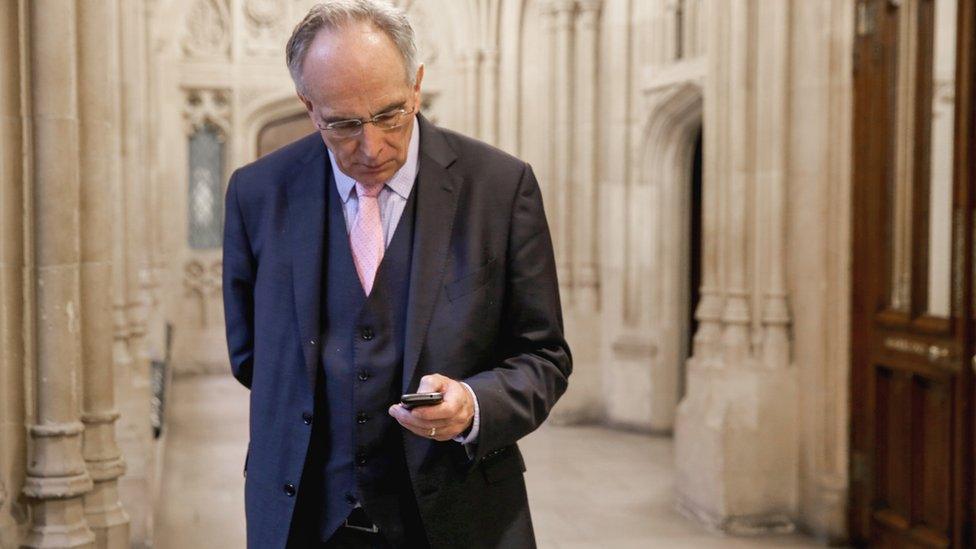

In recent years, a group of Tory backbenchers like Sir Christopher Chope, Peter Bone and Philip Davies have made a habit of "talking out" what they regard as vexatious, flabby, badly thought out bills.

So one of the first things any winner in the ballot should do is seek to persuade them not to target their particular measure.

It doesn't always work, but it's worth a try.

Friday sitting battle

To beat a filibuster, the promoter of a bill needs what's called a closure motion - a motion to put the matter to the vote.

The trouble is that, first, the chair won't allow that until there has been a substantial debate (at least a couple of hours) and second, the motion has to be supported by at least 100 MPs.

The idea is to stop something being forced into law by five votes to three on a sleepy Friday afternoon.

And because Private Members' Bills are debated on a Friday, 100 MPs must be persuaded to forego their normal day in their constituency to vote for the cause.

In normal times, it's a pretty good rough and ready test of whether a bill matters enough to become law - either it's so uncontentious that it is not filibustered and debates come to a natural end, or it is contentious but has enough support to clear that procedural hurdle.

So the MP proposing a controversial bill will need to build a coalition behind it, and conduct a whipping operation to ensure supporters turn up on the day.

The trouble is that during the pandemic, there can't be 100 MPs in the Commons.

And under Standing Order No 39A, voting by proxy is not allowed on any closure motions - which means that particular line of defence will not be available until the restrictions have been relaxed and closure motions will be possible again.

Tory MP Peter Bone is well practised at the art of filibustering

So what causes might surface this time around? It all depends on who wins a place in this year's ballot.

One of the winners might want to take forward the Climate and Environmental Emergency Bill being pushed by a number of green pressure groups.

There's an Assisted Dying Bill in the House of Lords, but the main backers of that cause in the Commons think it is premature to legislate and would probably try to talk an MP out of proposing such a bill.

There might be something on providing assistance to families who need representation at public inquiries, or a measure to regulate trailer parks.

Unless they already had a particular measure in mind, the winners of the next ballot will probably take a few weeks to decide what they want to do with the opportunity fate has presented them.

The winners are due to present their bills, which means announcing their titles and purposes on 16 June, so watch this space.