Non-doms: Why Labour squeeze on wealthy elite could backfire

- Published

Abolishing the non-dom status has become a key plank of Labour's policy platform

As Labour rides high in the polls, the party is threatening to scrap tax perks for the super-rich if it wins power.

Bashing the wealthy is not really Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer's style, but he has made an exception for those who claim special tax treatment known as non-domiciled, or non-dom, status.

If Labour wins the next general election, the party has pledged to scrap this "tax loophole" to raise an estimated £3.2bn a year.

Labour says it would use the money to train more NHS staff and offer free breakfast clubs for every primary school in England, at a cost of £2bn a year.

But the policy has given some wealthy people and their tax advisers the jitters, with some telling the BBC they're thinking about taking their money elsewhere, potentially leaving a gap in the UK's public finances.

Bad fortune

Dubai, Greece and Portugal. These are some of the countries that members of an economic elite have recently moved to instead of the UK.

The reason? The certainty of lower taxes.

One tax adviser, James Quarmby, says two clients with a business worth more than a billion were unnerved by Labour's policy and snubbed the UK in favour of residency in Greece, which also has a non-dom scheme.

In meetings with new clients, Labour's non-dom policy - and the party's double-digit lead in opinion polls - is often "the first topic of conversation", Mr Quarmby says.

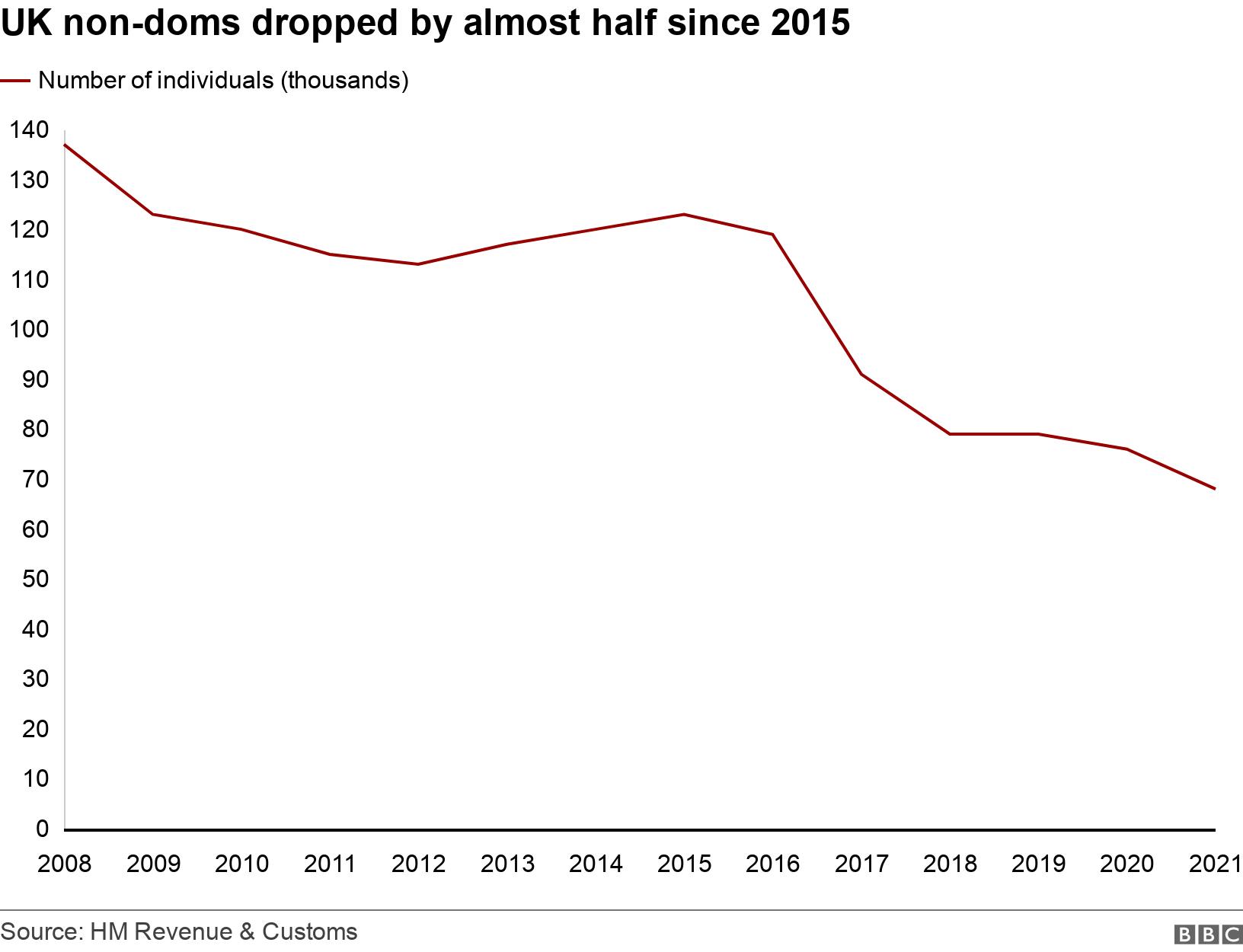

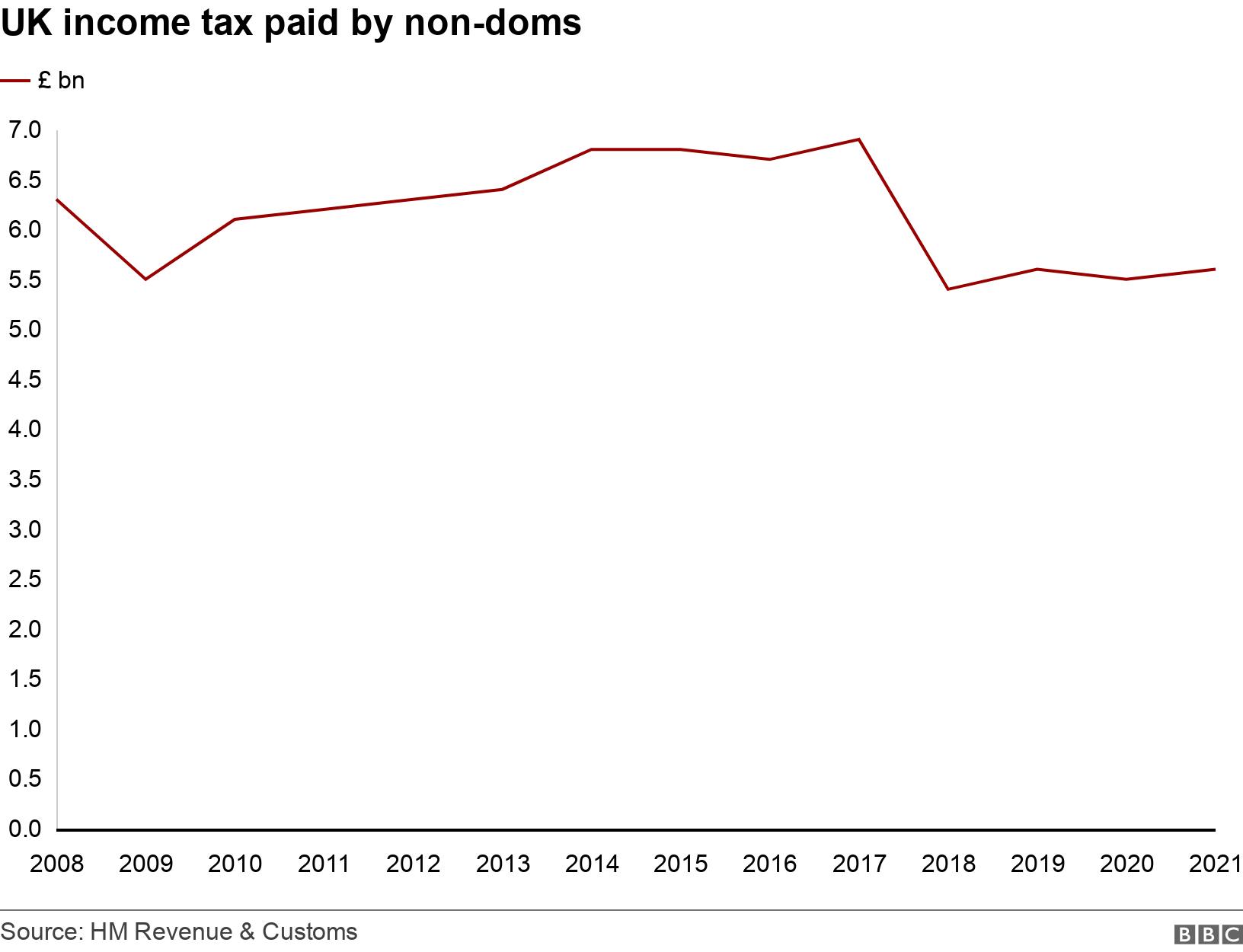

If those clients came to the UK now, they could join the estimated 68,300 non-dom taxpayers in the country. In 2021, they paid about £7.8bn in tax on their UK income, about 1% of national revenue overall.

On income and gains outside the UK, they paid nothing. Why?

Because that's the tax perk available to "non-doms", who declare themselves to be UK residents with permanent homes abroad. Once they've lived in the UK for 15 years, their tax-saving status expires.

For non-doms, their next move will depend on the finer details of Labour's policy, which are yet to be finalised.

For now, we know Labour would abolish the status and introduce a new tax scheme for temporary UK residents.

A Labour source said scrapping the tax breaks "is something we want to do as soon as we come in", but gave no specific timeline.

When changes were last made, in 2017, the Conservative government ended permanent non-dom status.

One former non-dom, who did not wish to be named, was among those who left the UK before the reforms came in. A French national who works in finance, he would only consider returning to the UK if he was able to reclaim non-dom status.

Now a resident of Dubai, where there is no personal income tax, he says the non-doms he knows are worried about Labour's policy and are already planning where they might go.

Non-doms make up a large proportion of finance jobs in London

If non-doms don't want to travel far, the Republic of Ireland is one option. It too has a non-dom regime, one that attracted a millionaire American following the UK's reforms of 2017.

The former UK non-dom says abolishing the status might deter high-paid talent. "It's difficult for people who have holdings in another country but want to work in the UK for, say, five years. It's messy."

That predicament will hardly pluck on Labour heartstrings, nor deaden the courage of the party's convictions.

The party says it will offer a new short-term tax scheme for temporary UK residents to continue attracting overseas talent, but has not specified how long that period would be.

Labour is sure that taxing non-doms on their worldwide income won't set off a mass exodus of the wealthy, as critics have long claimed.

Studies of tax data show very few non-doms responded to previous reforms by leaving the UK. One paper, external by the London School of Economics and the University of Warwick says the reforms in 2017 "led to just 0.2% of long-staying non-doms leaving the UK".

"Our best estimate is therefore that the same would be true if the regime were further curtailed or abolished," says Arun Advani, an economist and one of the study's authors.

Treasury scrutiny

The study divided tax experts the BBC spoke to for this article, with some critics arguing its findings were based on assumptions about the behaviour of non-doms.

The study's calculation that abolishing non-dom status would raise more than £3.2bn in tax each year has also been disputed. When the figure was put to Chancellor Jeremy Hunt last year, he said he had asked the Treasury to look into it.

Treasury sources say that analysis has not yet been seen by Mr Hunt, who is leaning towards keeping existing non-dom rules. Meanwhile, two sources with connections to the Treasury say its aides have sought expert advice on the options for reforming the system.

Treasury sources denied ministers are considering changing non-dom status.

That potentially leaves the path clear for Labour to use non-dom tax contributions to fund its policies.

To pay for its policies, Labour is relying on the calculations of academics, and the £3.2bn figure in one study.

Several billion "isn't going to scratch the surface", says Nimesh Shah, the CEO of Blick Rothenberg, an accountancy firm. What Labour hasn't done, the tax expert says, is a detailed study of the economic value of non-doms and their businesses to the UK.

Without that, non-doms are "an easy target for people to throw stones at", says George McCracken, a tax adviser to the super-rich. He says the UK's non-dom status had become "a political hot potato", one tossed around at the expense of Rishi Sunak, the prime minister.

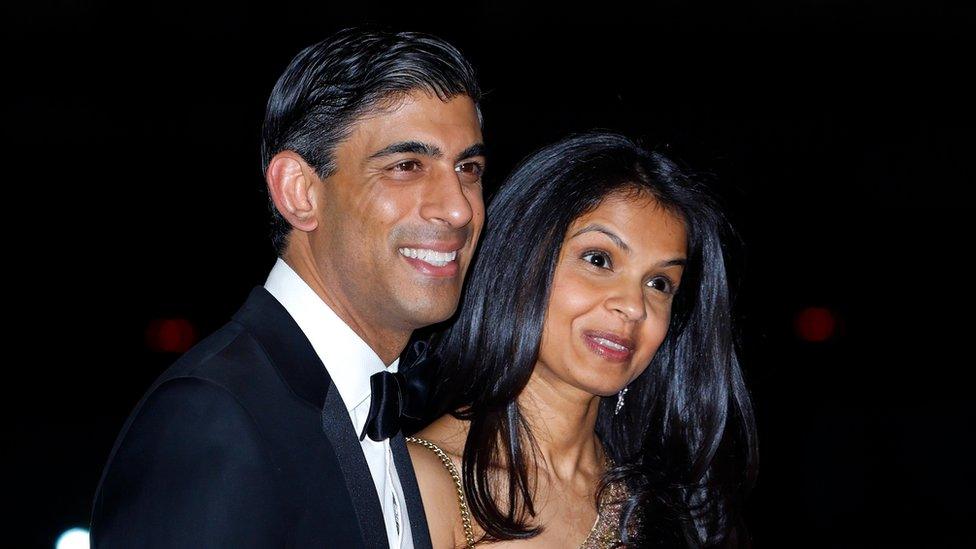

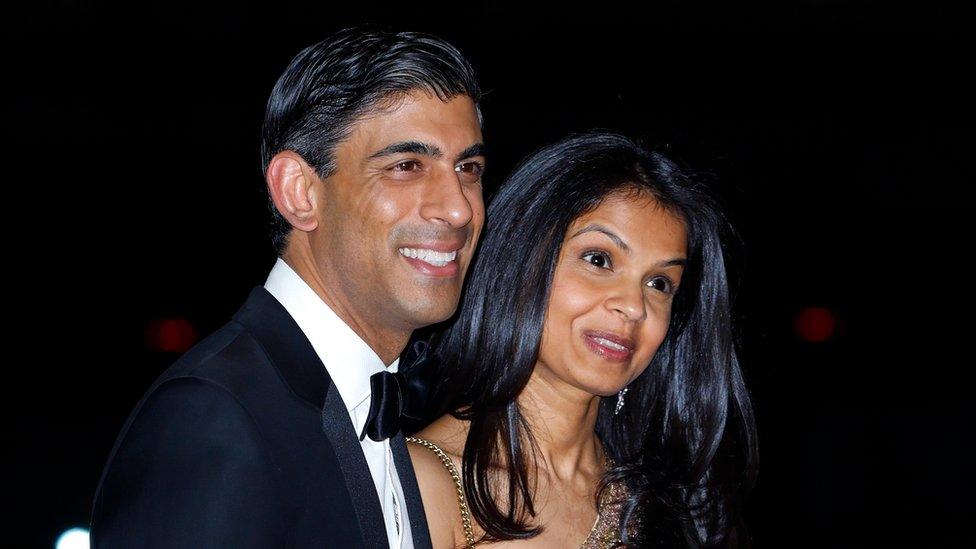

Mr Sunak's political stock fell last year after a media firestorm bounced his wife, Akshata Murty, into revealing her non-dom status. To quell the controversy, Ms Murty agreed to pay UK taxes on her overseas income while keeping her non-dom status.

Rishi Sunak's wife Akshata Murthy revealed she had been claiming non-dom status last year

The affair was seized on by Labour, whose leader and MPs railed against the "hypocrisy" of the then-chancellor's wife using a tax-saving scheme.

Since then, the "general mood among non-doms is that the UK is not very friendly anymore", says Mr Quarmby, the tax adviser.

There's a "very negative attitude" towards the status, one current UK non-dom says. She felt ashamed, and on reflection, has decided to give up her status and accept the consequences because "it's not a fair tax policy".

Even though she's an ultra high-net-worth person worth millions, she says scrapping non-dom status "would definitely not be a reason I would leave this country".

For a party that's courting business and rubbing shoulders with billionaires in Davos, is there a place for non-doms in Labour's "fairer, greener future"?

If tax advisers aren't sure yet, Labour's deputy leader, Angela Rayner, dropped a hint in a BBC interview last year.

Echoing a quip etched in Labour folklore, Ms Rayner said she was relaxed about people getting "filthy rich", before grinning and adding a caveat.

"As long as they pay their taxes."

Angela Rayner: I won't attack Sunak for being rich

Related topics

- Published23 January

- Published7 April 2022

- Published10 April 2022