Who is Nicola Sturgeon? A profile of the SNP leader

- Published

Nicola Sturgeon has led the SNP for less than three years, but is already leading them into a fourth election. Here, we look at the rise of the woman at the top of Scottish politics.

Born in the North Ayrshire town of Irvine in 1970, Nicola Sturgeon became an SNP member at the tender age of 16, having been inspired by a high-ranking female politician - but not in the way you might think.

It was Margaret Thatcher.

She told BBC Radio Four's Women's Hour: "Thatcher was prime minister, the economy wasn't in great shape, lots of people around me were looking at a life or an immediate future of unemployment and I think that certainly gave me a strong sense of social justice and, at that stage, a strong feeling that it was wrong for Scotland to be governed by a Tory government that we hadn't elected."

But, unlike the many who chose to support Labour - then the dominant force in Scottish politics - she was persuaded by the argument that that nation would only truly prosper with independence.

After studying law at Glasgow University and working as a solicitor at the city's Drumchapel Law Centre, Ms Sturgeon's entry into full-time politics came at the age of 29, when she was elected to the new Holyrood parliament in 1999, as a Glasgow regional MSP.

As a frontbench opposition spokeswoman, she sought to hold the Labour-Lib Dem coalition government to account on education, justice and health.

Nicola Sturgeon pictured alongside close friend Shona Robison in the original 1999 intake of MSPs

In the parliament's early days, Ms Sturgeon had a reputation for being too serious, which partly earned her the title "nippy sweetie" - but friends and rivals alike are at pains to point out her lighter side.

Fiona Hyslop, another long-serving SNP activist who is now Scotland's culture secretary, attested to Ms Sturgeon's strong sense of humour.

Recalling Ms Sturgeon in her 20s, Ms Hyslop, said: "She was always quite guarded, to make sure that she didn't do or say anything that perhaps would cause difficulty later.

"So she was always, in that sense, very sensible - but good fun."

One of her biggest political opponents, Michael Moore, who often found himself working with Ms Sturgeon during his time as Scottish secretary, jovially recalls her rehearsing Mandarin on the Edinburgh Airport runway while awaiting the arrival of the pandas from China.

The Salmond-Sturgeon leadership was a success for the SNP

Back in 2004, times were certainly serious for the SNP.

Beset by in-fighting and the negative publicity of a leadership challenge, the party's troubles were being exposed to voters in full view.

When John Swinney quit as leader, Ms Sturgeon saw her chance - knowing that although the situation had given her the opportunity to lead the party, the pressure was also on to unite the SNP as an election-winning force.

But then came the unexpected news that Alex Salmond would stand as leader - for a second time.

When he offered her the chance to run with him on a joint ticket as his deputy, Ms Sturgeon, who had always done her own thing when it came to politics, had to think it over. After reaching what she called an "instinctive" position, her leadership manifesto was withdrawn little more than a week after its launch, and the rest was history.

The Salmond-Sturgeon leadership was a success for the party.

Immediately after the leadership contest - and with her new boss still an MP at Westminster - Ms Sturgeon boosted her profile as the SNP's "Holyrood leader", grilling Labour's Jack McConnell at first minister's questions every week.

Nicola Sturgeon - a private life

Nicola Sturgeon says making independence appealing to women "will crack the referendum"

BBC presenter Jackie Bird, who spoke to Nicola Sturgeon, said: "She chatted to us in her kitchen which she revealed, with disarming honesty, she rarely visited. She also conceded that unless women could be persuaded to favour independence the referendum would not be won."

The work paid off with the SNP's 2007 election win, external, with Ms Sturgeon becoming Scotland's deputy first minister and health secretary.

She also won the Labour-held Glasgow Govan seat - the scene of past historic victories by SNP veterans Margo MacDonald and Jim Sillars.

At the same time, commentators noted Ms Sturgeon had undergone something of an image revamp and, it seemed, had adopted more of a common touch, which she later put down to having greater confidence in her abilities.

She began as health secretary by seeing through popular SNP pledges, like reversing A&E closures and scrapping prescription charges.

And she was later thrust into the international public eye during the global swine flu crisis, giving regular and incisive press briefings and updates after the first UK cases were confirmed in Scotland, becoming a fixture on 24-hour news channels.

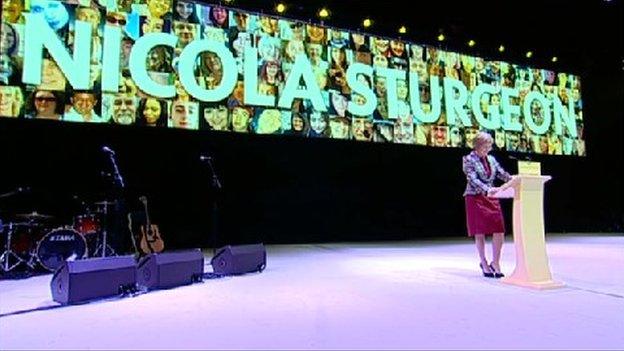

The SNP's campaigning has put Ms Sturgeon front and centre since she became leader

Her time at the top end of Scottish politics quickly became characterised by electoral success, with Ms Sturgeon spearheading the SNP campaign as the party won an unprecedented majority at Holyrood in 2011.

She later described the result - and the dismantling of Labour strongholds across the country - as having broken the mould of Scottish politics, and put the SNP's success down to being "in touch with the country it served".

Some five years after taking on the health brief, Ms Sturgeon accepted one of the Scottish government's biggest roles, as the "Yes Minister" overseeing the independence referendum.

Westminster's negotiator, the then Scottish Secretary Michael Moore, saw Ms Sturgeon's appointment as a sign things were about to get serious. He later said she was straightforward to work with "once you understand where she's coming from".

The dream shall never die

The referendum itself, on 18 September 2014, was a massive disappointment for everyone on the side of independence. They were beaten by 55% to 45%.

It was a severe blow for Ms Sturgeon - she told reporters she was "deeply disappointed" as the result became clear, albeit "exhilarated" by the campaign - but it was ultimately one which would propel her to the top of Scottish politics.

Within hours of the final result being confirmed, Alex Salmond announced he would step down as first minister and leader of the SNP.

Ms Sturgeon was immediately tipped as the natural successor; she said she could "think of no greater privilege than to seek to lead the party I joined when I was just 16".

Ultimately, there was no competition. More of a coronation, at the party's conference that November - although the new SNP leader said she would have "relished" a contest.

Nicola Sturgeon went on a stadium tour after becoming SNP leader

She opened her premiership more like a rock star than a politician, embarking on a sold-out stadium tour amid a blaze of popular support. Party conferences and speech events followed suit, employing slick presentation to build Ms Sturgeon into an almost presidential figure.

And in the meantime, despite the disappointment of the referendum defeat the SNP's membership surged, with tens of thousands of new members signing up - and Ms Sturgeon was to ride this wave of support to new highs.

Ballot-box behemoth

The party had already been the biggest kid on the block in Scottish politics; it had won a Holyrood majority in 2011 and the most council seats in 2012. But with Ms Sturgeon at the helm the party truly became an electoral juggernaut, starting with the 2015 general election.

The results were unprecedented. They were stunning. Ms Sturgeon's troops came close to sweeping the board entirely, taking 56 of the 59 seats in Scotland.

The swingometer went off the charts; huge Labour majorities were wiped out, with heavyweights including Douglas Alexander and Margaret Curran defenestrated - the former by a 20-year-old named Mhairi Black.

SNP wins landslide general election victory in Scotland

The trend continued in the 2016 Holyrood elections, with the SNP romping to victory while campaigning heavily on Ms Sturgeon's personal popularity.

The cover of their manifesto simply bore a picture of the leader, and the single word "re-elect".

It was another big victory. Not only did the SNP win more than a million votes and a record 59 of the 73 constituency seats, with a handful more from the top-up lists, the result gave Ms Sturgeon a "clear and unequivocal" personal mandate as first minister.

There was no repeat of the 2011 majority, but that had been almost a freak result; the SNP had broken the system by sweeping up both constituency and list seats. Because the party gained constituency seats in 2016, it was denied list seats in areas like Glasgow, where they won every first-past-the-post contest.

Just a few years earlier it had been unthinkable. From Shettleston to Springburn, Glasgow, once Labour's great Scottish stronghold, had turned yellow.

The SNP later completed the electoral sweep of the city in the 2017 council elections.

Five questions to Nicola Sturgeon

Which person has most inspired you? - "My Mum."

If you could do one thing for women, what would it be? - "Equal Pay."

When were you happiest? - "When I married Peter."

What makes you angry? - "When people talk down Scotland's potential."

What's your favourite holiday destination? - "In Scotland, it's Skye and abroad it's Portugal."

Five more questions - in a lift

SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon took the five-floor lift challenge

After her first Holyrood victory as first minister, Ms Sturgeon outlined education as the number one priority of her government. She stressed that she wanted to be first minister for the whole country, not just the SNP and Yes side - in effect, to build a political legacy away from the binary question.

But for all the debate about the length of a political "generation", the issue of independence never really came off the agenda. It was still the hot topic of debate and had become a decisive factor at the ballot-box, with Ruth Davidson building a Conservative revival by pitching her party as the defenders of the union.

In truth, Ms Sturgeon would probably have preferred to wait a few years before going back down the referendum road, to move on from the 2014 campaign and maximise her chances of victory.

But then Brexit changed everything.

The UK's exit from the EU presented the SNP with an opportunity, as well as a challenge. A new layer of complexity in the political picture, a new binary issue to factor in, but perhaps a chance to resurrect the dream of independence.

The SNP's 2016 manifesto (which had her face on the front) had raised the possibility of Scotland taking a fresh look at going its own way if voters north of the border backed Remain, while the UK as a whole voted to Leave the EU.

That is, of course, exactly what happened.

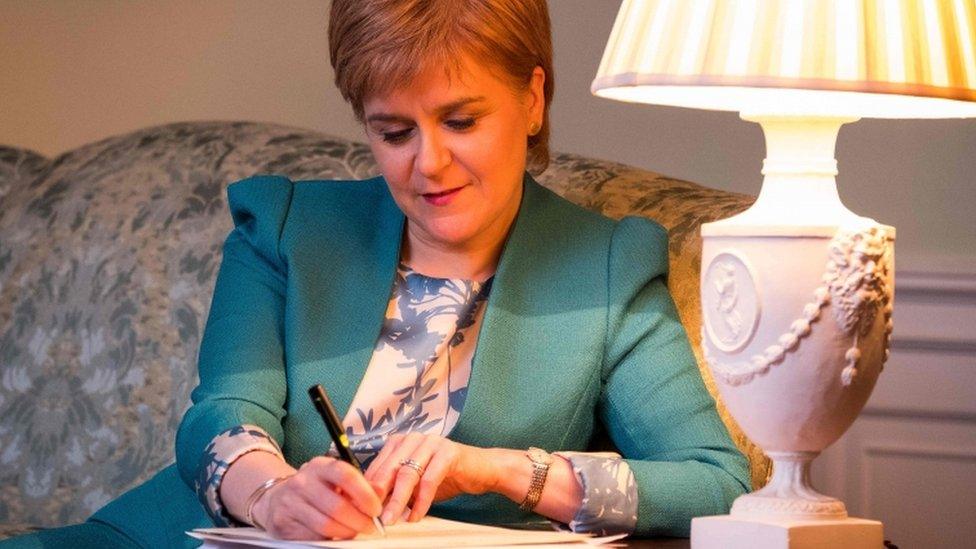

Ms Sturgeon wrote to Theresa May demanding the power to hold a second independence referendum

Ms Sturgeon is normally characterised as a canny, relatively cautious politician; a thinker, far from the mould of her comparatively gung-ho predecessor at Bute House.

But when it came to Brexit and the chance of what quickly became known as "indyref2", Ms Sturgeon threw caution to the wind.

Months of debate and megaphone diplomacy followed. Ms Sturgeon put forward a paper of proposals, which was roundly rejected. But it felt like it was all leading up to one thing.

Just as Theresa May was preparing to trigger the formal Brexit process, Ms Sturgeon dropped her bombshell: a bid for a second independence referendum.

From there, the two women traded constitutional blows at a dizzying pace.

Mrs May said (repeatedly) that "now is not the time" for indyref2. Ms Sturgeon sought and won the backing of Holyrood, and fired off a formal demand for a referendum. And then Mrs May called a shock general election.

In Edinburgh and London, it's possible the stakes have never been higher for either leader.

In terms of her private life, the first minister is married to Peter Murrell - who is also chief executive of the SNP, making them perhaps the ultimate power couple of Scottish politics.

The pair exchanged vows in 2010, after meeting 15 years previously at an SNP youth weekend in Aberdeenshire.

That said, Ms Sturgeon still finds time to retreat from politics by pursuing her great love of reading, and watching X-Factor.

Her mum Joan - herself an SNP politician, serving at one stage as the Provost of North Ayrshire - joked: "She can relax - there's always one eye on the phone, but I think she's fairly relaxed.

"The phone is never switched off - many of my family can vouch for that."

Nicola Sturgeon with her husband Peter Murrell

Expectations for the SNP under Ms Sturgeon are sky-high. Having swept Westminster, Holyrood and local council elections all within her first three years in the job, they are generally expected to win more or less every contest they enter.

And the leader's personal brand is at the heart of this; most of the merchandise at SNP conferences bears some form of the "I'm with Nicola" slogan.

Indeed, the first minister has transcended the need for a surname even among opposition circles. Say "Nicola" to more or less anyone in Scotland, and they will know exactly who you mean.

All of which only makes her job harder.

Hers is now after all a third-term government, with 10 years in power under its belt. In no democracy could such an established power be universally popular.

And she is now leading the SNP into a snap general election campaign where they must defend nearly every seat in the country; a taller order can hardly be imagined.

But if her history is any guide, Nicola Sturgeon will relish the challenge.