At-a-glance: The Penrose report

- Published

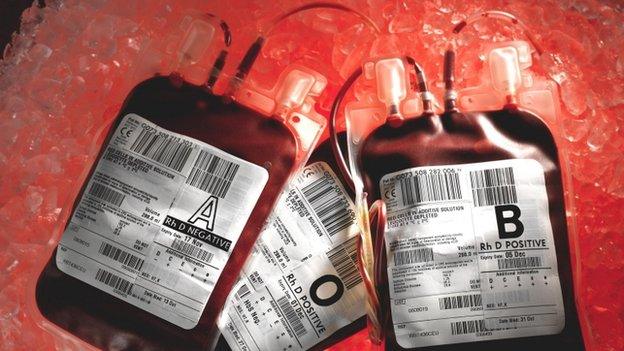

The long-awaited report by Lord Penrose, external into patients being infected by contaminated blood supplies in the 1970s and 1980s has been published.

While thousands of people across Britain were infected with Hepatitis C and HIV through NHS blood products, the inquiry was focused on victims in Scotland.

It has been described as the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

Background

The report looked at people in Scotland who were infected with blood-borne viruses - HIV and Hepatitis C - in the course of medical treatment on the NHS.

The period scrutinised by the inquiry began on 1 January 1974 and ended on 1 September 1991, when screening of donated blood for the Hepatitis C virus was introduced throughout the UK.

The infections came from blood which had been donated by people who had the viruses.

Some were infected during blood transfusions for illness, injury or during childbirth or surgery.

In the case of haemophilia therapy it occurred as a result of transfusions of blood products made from large pools of donations and given to remedy the deficiency of clotting factor in a patient's blood.

Numbers infected

About 2,500 people are thought to have been infected with Hepatitis C by blood transfusion on the NHS in Scotland. At least 18 were infected with HIV.

The report said a further 478 bleeding disorder patients (haemophiliacs) are thought to have been infected with hepatitis C, and 60 with HIV, from blood products.

Knowledge at the time

A statement from Lord Penrose read out at the publication of the report said: "The state of knowledge of each virus informed the inquiry's assessments of the acting of doctors."

HIV was first identified in 1983 but international acceptance did not "crystalise" until 1984.

The report said testing for HIV in blood products was not possible before the virus was identified.

The Lord Penrose's statement said: "Some commentators believe that more could have been done to prevent infection in particular groups of patients.

"Careful consideration of the evidence has however revealed few aspects in which matters should or, more importantly, could have been handled differently.

"In relation to HIV/Aids it appeared to the inquiry that when actions in Scotland were subjected to international comparison they held up well.

"Once the risk had emerged all that could reasonably be done was done in the areas of donor selection, heat treatment of products and screening of donated blood.

"Other than by a general cessation of therapy with concentrates, the infection of haemophilia patients with HIV over the period 1980-1984 could not have been prevented."

It said the science of the hepatitis C virus was not understood in the 1970s and identification of the "causative virus" did not take place until 1988.

Lord Penrose's statement said: "As with HIV it was not possible to test the native blood for the virus until the virus had been discovered, although alternatives including testing for other indicators of infection were adopted in some countries."

The first test kits for hepatitis C virus only became available in November 1989.

Delay in screening

The inquiry did point to a delay in the introduction of the screening of donated blood for the hepatitis C virus.

It said a decision on screening should have been taken by middle of May 1990 rather than in November 1990. It then took 10 months to implement. Issues in England and Wales led to a delay in Scotland, despite it being ready to implement the screening.

Blood from prisoners

The last year that blood donations were collected from prisoners in Scotland was 1984. By this time only a small proportion of blood was coming from prisons.

The report said the Home Office in the 1970s liked blood donations from prisoners as it was thought they were making "restitution" for their crimes.

But there was little information on how many prisoners were drug users and thus a risk of having infections.

The inquiry heard from Scottish National Blood Transfusion experts that "with the benefit of hindsight" taking blood from prisoners was "inadvisable and should have stopped earlier".

Risk of transmission

Heat treatment ended the transmission of HIV by NHS blood products in Scotland by October 1985, and from commercial products by about the same time.

The report said there may subsequently have been "isolated" infections from donors who had the virus but had not created antibodies.

Further developments in heat treatments also made blood products safe against the hepatitis C virus by 1987.

Recommendation

The inquiry's single recommendation is that the Scottish government takes all reasonable steps to offer a hepatitis C test to everyone in Scotland who had a blood transfusion before September 1991 and who has not been tested for the disease.

- Published25 March 2015

- Published25 March 2015