Taxing times at Holyrood

- Published

Things seldom stand still. Politics contains its own momentum, driving matters forward to the next controversy, the next announcement, the next election.

That is eminently so with regard to the pending Holyrood contest. Already, it appears evident that there will be significant controversy over tax plans which, to be clear, have yet to be finally endorsed and which, if they are, will not be implemented until next year, long after the ballot boxes have been packed away again.

Watching recent financial exchanges, including John Swinney's Budget, at Holyrood, it seems clear to this observer that Scottish devolved politics has already changed substantially.

MSPs are well used to discussing spending. Now they face the prospect of considering taxation too. And that is plainly concentrating minds.

To recap. The Scottish Parliament has had the capacity to alter tax from the outset - the so-called "Tartan Tax" power to vary the standard rate of income tax by +/- three pence in the pound. That has never been used for the reason that it raised too little to justify the concomitant controversy.

Tough negotiations

From April this year, Holyrood will set an income tax rate under the sharing plan devised by the Calman Commission. Mr Swinney has already declined to use the power to change the Scottish rate, noting that he is unable to distinguish between the high and low paid in so doing. He must levy uniformly across the bands.

But from April 2017, should Westminster and Holyrood so decide, the Scottish Parliament will control all rates and bands of non-saving and non-investment income tax.

This remains undecided because the Scottish and UK governments have yet to conclude an accompanying bargain on the fiscal framework governing the future indexation of the continuing block grant which will fund those elements of Scottish spending not covered by Scottish income tax.

The negotiations are tough. A relatively robust line from the Treasury has been matched by an orchestrated warning of potential failure from the Scottish government side.

Both positions are valid and understandable. However, I believe that the prize of a deal is so substantive for both sides that a settlement will be reached.

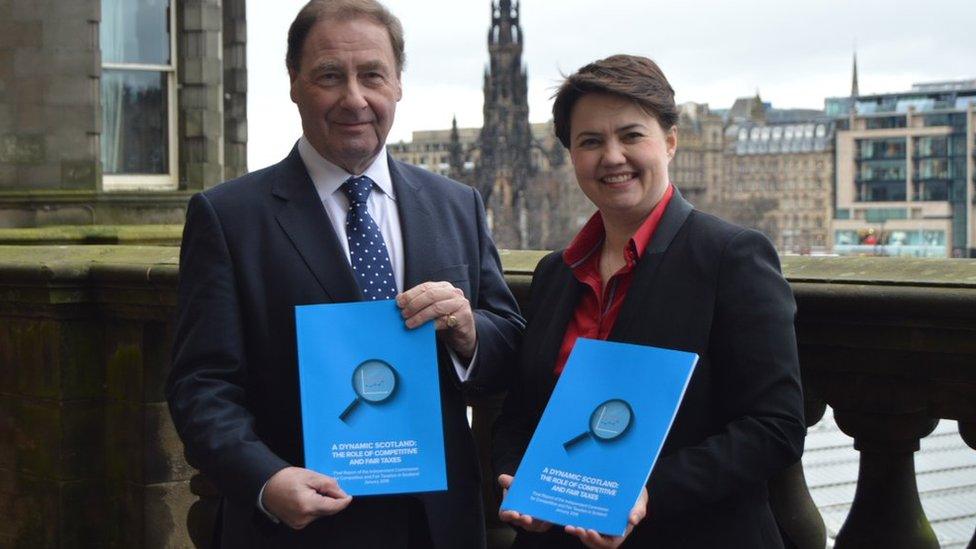

A commission set up by the Scottish Conservatives to examine taxation in Scotland published its report on Monday

A deal means the Scotland Bill becomes an Act, if Holyrood agrees. Scotland Act equals new tax powers from next April.

With that prospect on the horizon, the offers are already beginning to emerge. The Conservatives, it would appear, are engaged in a choreographed gavotte, swirling steadily and elegantly towards an offer to cut Scottish income tax.

Today emerged the thinking of the commission set up by the Tories. Chaired by Sir Iain McMillan, they favour a reformed council tax, a business rates freeze and, eventually, the abolition of residential Land and Buildings Transaction Tax.

But it's income tax which is the Premier League. On that, they say there should be a new 30p midway rate to ease the transition to upper rate tax for aspirational families. They say the overall tax burden in Scotland should be no higher than elsewhere in the UK - with the potential for a tax cut, if feasible.

For now, Ruth Davidson says she agrees with the underlying thinking - that Scotland already faces disadvantages such as remoteness from big markets and should not add to those with higher tax. For detail, we will have to hold fire for now.

Concerned questions

The Liberal Democrats will similarly set out their thinking although Willie Rennie has talked of the need to invest in education. The Greens say improved public services in Scotland cannot be funded without higher impositions, potentially affecting both income tax and council tax.

Labour has set out some early thinking, including a restored 50p upper rate for those earning more than £150k a year.

The SNP are looking at that but I hear one or two concerned questions behind the scenes. Would such a tax raise significant sums? What if, within a continuing UK, top earners registered elsewhere to sidestep the Scottish rate? What signal does it send about Scotland being open for business?

It is a conundrum for the SNP. As the governing party - and quite possibly the continuing governing party - they want nothing that jeopardises the economy of Scotland, particularly as future public services will be more dependent than ever on the buoyancy of that economy, given the new tax powers.

Equally, though, they want to match - more than match - the anti-austerity, pro-public services rhetoric of their Labour opponents.

PS: Have been enjoying what we must now call the Burns Season. Tonight will be my third Immortal Memory in a few days. However, nothing quite matched the "Kilmarnock Edition" served up at Tannadice on Saturday. Truly immortal, guys. Thanks for the memory.