The economics of Brexit - best and worse case scenarios

- Published

A six-page letter has altered the course of British history and its place in the world. It may also have begun the unravelling of Britain itself.

The letter is significantly more co-operative in tone than much of the rhetoric that got the country to this point.

The word 'co-operate' appears five times, 'partner' nine times, and 'citizen' seven times. There's no mention of the word 'budget' or 'cost', or of 'taking back control'.

There's a threat in there that if there isn't a trade deal between the EU and UK, the efforts to combat crime and terrorism will be weakened - without saying how or why.

But it makes clear that the negotiations ahead are overwhelmingly about the economy, with the aim of getting to a "bold and ambitious free trade agreement", based on "deep, broad and dynamic co-operation".

So where have we got to, and what does the letter tell us?

It hasn't been as bad as feared so far, has it?

The main impact has been to the value of the pound and, through that, to imported inflation. Arguably, the economy needed that anyway. By buying more than Britain was selling, it was drawing in capital from overseas, and it didn't look sustainable. With prices lower in sterling, exports have been doing nicely.

Consumers have kept consuming, at least until recently. With interest rates low, they've cut down on savings, and boosted borrowing. That doesn't look sustainable either, least of all as price inflation is poised to overtake earnings growth.

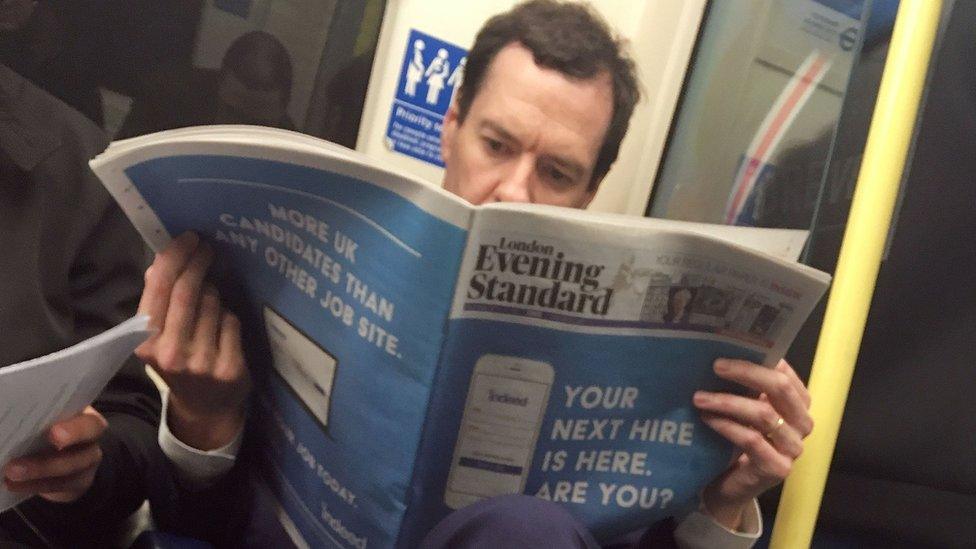

George Osborne's dire predictions have yet to be borne out by events

There were many dire warnings about economic collapse immediately following the vote, including an emergency budget and further, much more drastic spending cuts. They've proven to be vastly overblown.

The chief scaremonger, George Osborne, has gone off to advise Blackrock investment fund and edit the Evening Standard.

So can we trust predictions of the medium to long term?

They remain forecasts. But if true, they mean the economy will grow more slowly than it would otherwise do, at least over the next 13 years, leaving a gap of around 8% where EU membership might have taken us.

That assumes a loss of the dynamic impact of immigrant workers, and less inward investment. It is with new ways of working, often brought by foreign firms and helped by foreign workers, that productivity is driven faster. So without that, expect British productivity to slow further, when it's already poor.

The more positive outlook is that the gap will be filled by faster growth through trade deals struck elsewhere, and by a reduction in regulation from Brussels letting businesses grow faster.

What's the best that can come of Brexit, in terms of the economy?

The best outcome would maintain open trading access, with a simple, seamless transition of laws and regulations for goods and services, retaining complex supply chains for manufacturers.

The Great Repeal Bill, to be published on Thursday, is intended to start that process, transferring all those amassed European laws into British law, at least for now.

There's a big question of how much those rules and regulations will get unpicked, dumped or reworked. It probably depends on who has the loudest lobbying voice.

For instance, some will want to de-regulate labour markets, perhaps reducing the maximum working week which came from an EU directive and which has cost companies and public services a lot. Worker representatives will be lobbying to ensure that doesn't happen.

In the sunniest outcome for Brexiteers, immigration policy could focus on recruiting only the most productive immigrant workers, then making sure they don't stick around long enough to become a net drain on public services.

What would the worst outcome look like?

The chairman of the Scottish government's EU advisory group, Prof Anton Muscatelli, says Brexit would hit Scotland's economy

For those who see storm clouds over the British economy, none of that happens. Access to markets is hampered by customs, paperwork showing proof of origin and some tariffs.

Different sectors would be affected differently by a shift to what are known as World Trade Organisation, or WTO rules. Scotch whisky, for instance, would continue to see tariff free access to European markets, because that is already on offer to other countries without an EU trade deal.

But the car industry has a lot to fear from that; a 10% tariff on car sales into EU markets, other tariffs on the many components which cross borders in the supply chain, and the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders estimates £1,500 on every EU-manufactured car imported into Britain.

The impact on services is more complex, and harder to see, but potentially very serious. Financial services can operate in every EU country at present, without needing a licence in each one. If that 'passporting' right is lost, and seems likely, that would impose a big cost to set up in each country.

Simply retaining current contracts is causing concern. Under different legal circumstances, they face the requirement to redraw them. Again, it depends on what can be negotiated to minimise such complexity.

Will Scotland be affected differently from the rest of the UK?

That depends how different sectors are affected by the outcome of negotiations. A special deal could be done for car manufacturers, for instance, mainly in the Midlands and North of England. (Some think such a deal has already been done.)

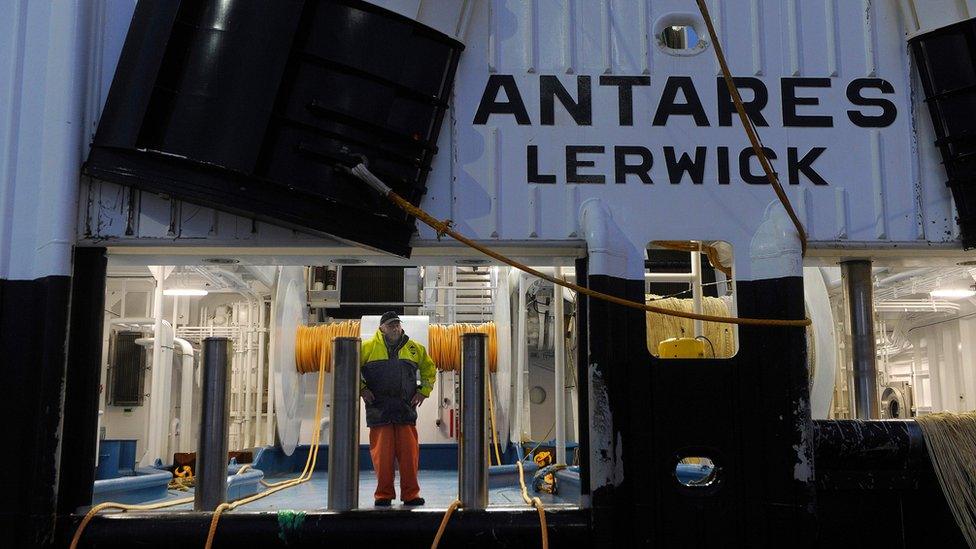

But fishing is one sector at special risk, even though skippers were those most eager to see a Brexit vote. More than 70% of UK deep sea fishing is in Scotland. (I wrote about this in October.)

It will be a priority for French, Spanish and probably Irish negotiators to retain access to British waters.

Relative to the rest of the economy, the size of the British fishing industry might look expendable, as it did back in the early 1970s.

If not, and access is denied, a suggestion that comes from a French businessman exporting shellfish from Glasgow is that there won't just be blockages in negotiations, but blockades at French ports. Ronald Scordia can foresee problems in getting his fresh and sometimes live catches to French, Spanish and Italian markets.

Angelbond, his French-owned company, is looking to expand in Glasgow, but also to hedge against Brexit risk by opening up operations in Ireland as well.

What about the migration of workers?

Much of the risk and opportunity around Brexit is common to Scotland and the rest of the UK, but demography is one area where Scotland has the most distinctive problem.

Immigrants are more likely to set up businesses. One of those I've heard from recently is Petra Wetzel, German founder of West brewery in Glasgow. She says that if she's forced to leave the country, it will be by being dragged, and she'll take a business with her, employing 125 people.

A third of them are EU nationals. Another company with deep roots in Scotland, publisher Harper Collins, is suffering the impact of EU nationals leaving the Bishopbriggs plant already, according to its chief executive Charlie Redmayne speaking at the London Book Fair.

It is almost entirely through immigration that Scotland has turned around its declining population. Without more young working age people, it was heading into serious problems.

Prof Anton Muscatelli, principal of Glasgow University, economist and chair of the Scottish government's advisory group on Brexit, told me that by 2015, Scotland was home to 181,000 non-UK EU nationals. Of them, 115,000 were aged between 16 and 35.

He says that has turned round Scotland's demographic challenge, bringing skills. It has "boosted and reversed the decline in Scottish demography, and in terms of Scotland's prospects, that is the key".

If the home-grown population is to make up for the departure of such people, they will have to train, work hard, accept pay that's competitive with trading partners, and have more babies.

How would things be different if Scotland were independent?

That's a big question. I had a look at that a couple of weeks ago. Happy reading.

- Published28 March 2017

- Published16 March 2016

- Published1 March 2017

- Published5 December 2016