Avoiding the exam reveal car crash

- Published

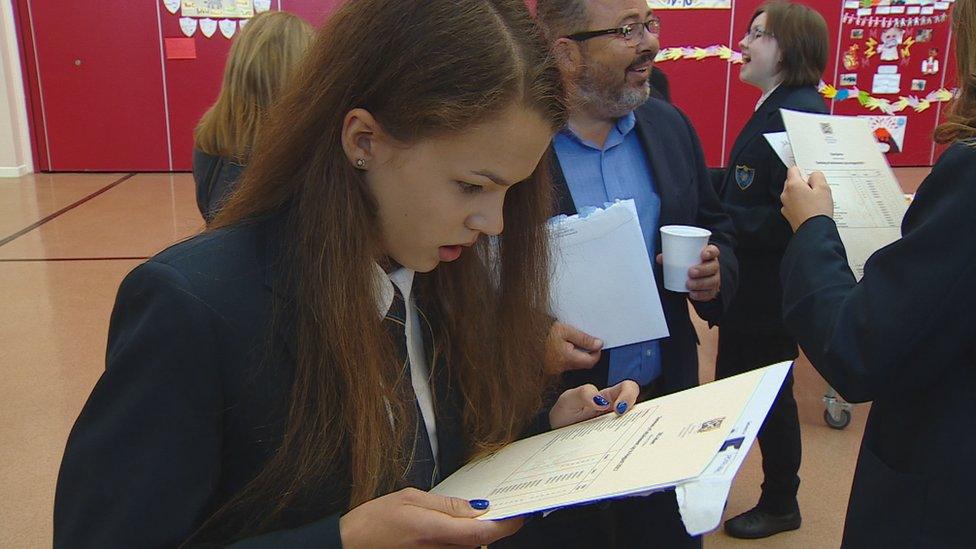

Reporting Scotland showed pupils at Airdrie Academy opening their results

It is what is known as car crash television and it has been widely shared on social media.

Teenager Liam Scroggie opening his A-level results live on Good Morning Britain, external got bad news, missing out on the grades he needed to get into his choice of university.

It was certainly uncomfortable viewing and the sort of moment I have always dreaded presiding over.

My heart went out to him.

As the BBC's Scottish education correspondent, I've sometimes faced criticism - occasionally from teachers and sometimes from other individuals - for filming young people getting their exam results or putting them live on air at such a nerve-racking moment.

Sometimes the concern expressed is for the wellbeing of the youngster.

And sometimes it is founded in a belief that all news outlets focus purely on the achievements of high-achieving pupils in leafy suburbs while ignoring the majority.

Sometimes the concern is that we are implying that a school's performance is being judged by the exam results in isolation.

These are all very important and legitimate points to make.

But I often wonder if the people who have made these points to me have actually seen or heard what we do on Reporting Scotland or Good Morning Scotland year after year, as they are all issues we are well aware of.

Or are they basing their view on an impression that "the media" all works together in one way?

Covering the exam results poses some stylistic challenges as well as editorial and ethical ones.

It is an important day in the news diary and one of the most important days in the lives of the youngsters.

So is it fair to show young people at a potentially life-changing moment?

It is worth making the point that most people who get their Higher results are normally old enough to get married, join the army or vote in Scottish elections. But there are important ethical and editorial questions.

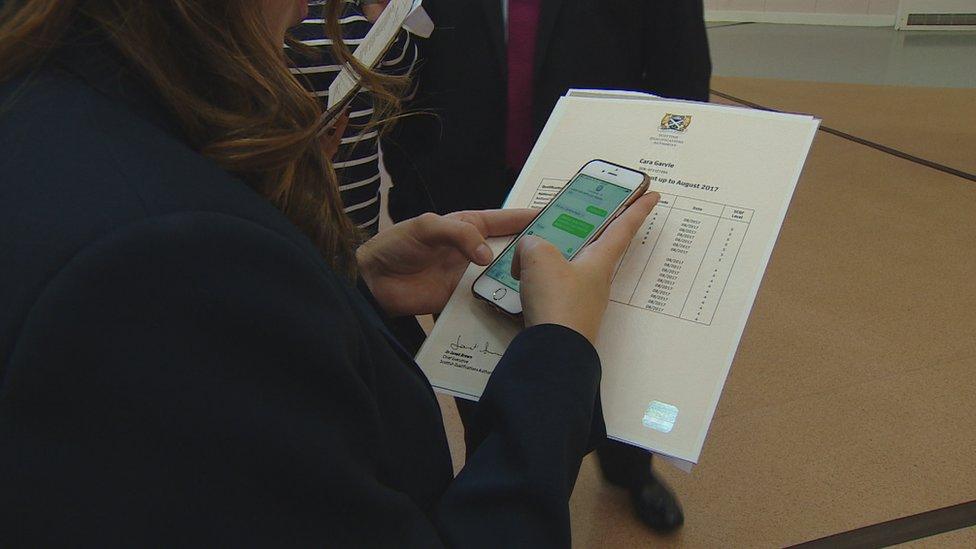

In Scotland, youngsters receive their results privately at home - by the post, by e-mail or by text.

So getting a group of youngsters together to get their results in public involves a degree of artifice and this should always be acknowledged on air.

How do we do it?

Generally we focus our coverage on one particular school and in recent years the schools we have picked would not have come close to the top of any newspaper league table.

Indeed BBC Scotland actively avoids using schools in affluent suburbs on results day and attempts to ensure a broad range of youngsters are featured - not just confident students from middle-class families who grew up with a family expectation that a place at a top university was all but inevitable.

It could legitimately be argued that this is unfair on youngsters who have worked very hard for brilliant marks but in news terms the reason for doing this is simple: exam results day offers an opportunity to discuss what the Scottish government would see as a defining mission, closing the attainment gap between youngsters from relatively rich and poor backgrounds.

For example, we may pick a school where a teacher can discuss the challenges the school has faced or how a growing number of their pupils are now achieving at least one Higher.

The other reason for attempting to include a wide range of students is that this helps demonstrate how results day in Scotland is now meant to showcase how achievement takes a number of forms.

Five As in Highers or good Advanced Highers are only one, very specific measure of achievement.

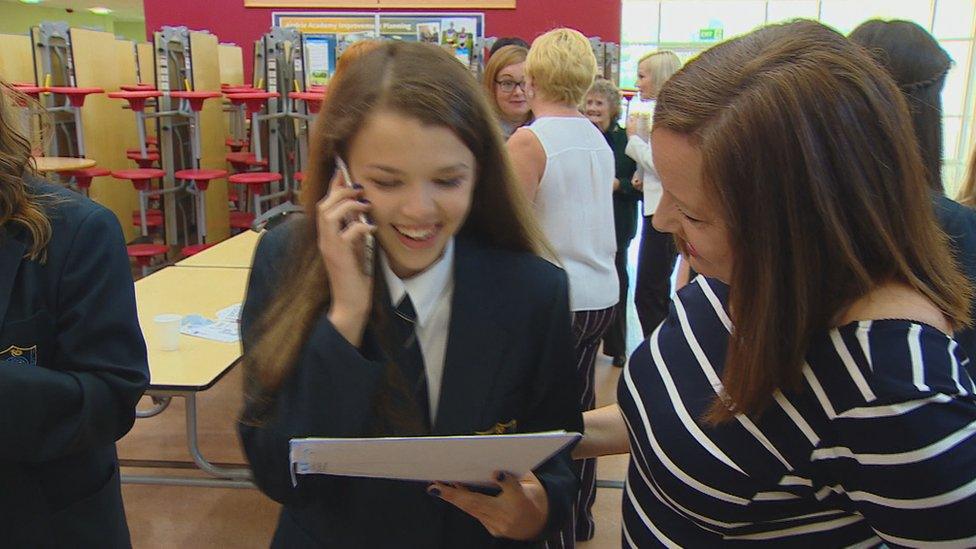

"I got a B in my English," exclaimed one joyful youngster in my television package on results day this year.

Her joy was infectious and for her a B was a real achievement to be proud of.

The context of the coverage is one thing - what about the ethics of putting young people live on air at such a key moment.

The welfare of young people is important to the BBC generally. We would not seek to upset or humiliate a child in any of our work.

As I said, we make special arrangements with schools and the SQA so some youngsters can get their results live.

We take all reasonable steps to minimise the likelihood of a young person being left distressed if they get "poor" results live.

Generally we pick a school in June - sometimes this will be a school which we have already established a relationship with.

The school will invite a group of youngsters along to specially receive their results - only a few will be expected to actually get their results live.

We also encourage the school to let the youngsters bring along parents to watch and offer support.

Schools have advance notice of the results and on the day, shortly before we go on air, the head will ask some of the youngsters if they'd like to open their results live.

The head knows these young people will get good news - results at least as good as the ones they had been hoping for.

The others act as an audience, offering their friends encouragement.

Because such a large number of young people are invited along, there is no implication that the others are set for disappointing news - indeed sometimes the youngsters who turn out to have got the "best" results are too shy or nervous to go on air.

It's a matter of who might have a good story to tell or who might feel personally comfortable going on air.

Then, of course, there is the question of the narrative in our finished piece.

This needs to reflect how the exam results are viewed in Scotland and how they are not seen in isolation as a measure of a school's performance.

We also need to reflect how disappointing results are not the end of the road and not the devastating blow they may seem at the time to someone who failed to meet their conditional university.

This seems to have been the case with Liam Scroggie, who despite his TV humiliation has been accepted by Hull University.

All news is ultimately about both storytelling people in some way - their experience, their views, their life story.

As one of my most distinguished colleagues has said before: "The most important quality a good journalist has is empathy".

Coldly reading out statistics in a studio would do no favours to the young people who have something to celebrate - especially when some of those who might ask me about our results coverage would also be the first to express concern that young people often only make the news if they are in trouble.

- Published8 August 2017