When is an island not an island?

- Published

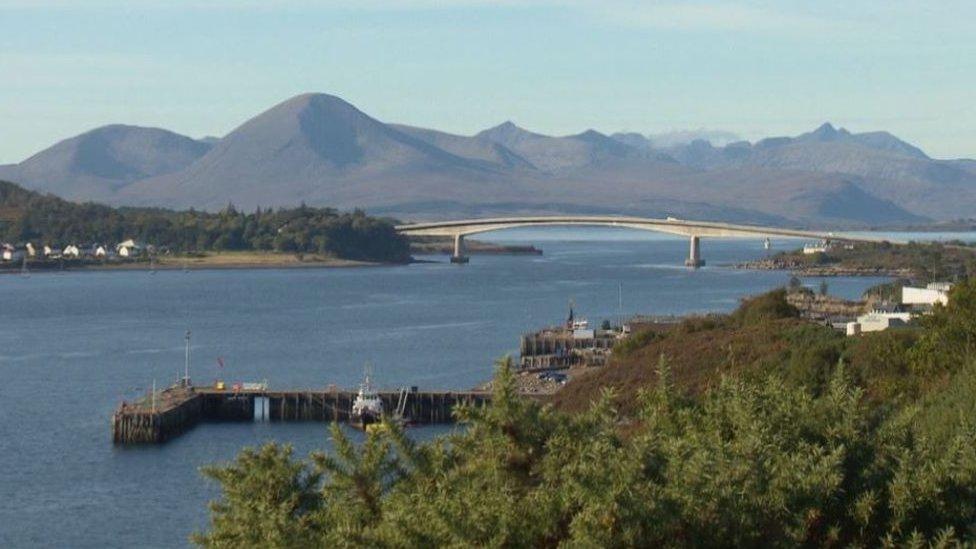

The Skye bridge was opened in 1995

An MSP has questioned whether Skye is a "real island" on account of the bridge linking it to the mainland. But what is a "real" island? To put it another way, when is an island not an island?

John Mason provoked an audible intake of breath from the rural economy committee when he suggested that Skye "doesn't have the problems of ferries and transport which real islands do" on account of its bridge.

The committee's convener Edward Mountain - not a real mountain - was quick to underline that "I'm sure we can all agree that Skye is an island", and Skye MSP Kate Forbes noted that "we'd have to rewrite the Skye Boat Song" if Mr Mason was right.

But this is not the first row over what is or is not an island in Scotland. In 2011, Argyll and Bute Council saw its budget shrink due to Seil being declared no longer deserving of island funding, on account of its road bridge.

So what are the facts behind this?

To start with, this is not an issue unique to Scotland. The South China Sea is currently a hotbed of rather more serious tensions over the status of various artificial islands, which have been built on top of coral atolls and rocks.

At one point in 2003, the EU claimed that Britain was not an island, external, in a proposed new definition that excluded anything "attached to the mainland by a rigid structure".

And to consider the contents of this rabbit-hole on an even greater scale, Australia, at 7 million square kilometres, is considered a continent, not an island, while the smaller but still massive Greenland, at 2 million sq km, is an island, not a continent.

Above water

The Scottish government's Islands Bill, which prompted Mr Mason's chin-stroking, describes an island as "a naturally formed area of land which is surrounded on all sides by the sea (ignoring artificial structures such as bridges), and above water at high tide".

That seems fairly reasonable, but it appears to go against a move the government itself made in 2011, when it apparently reclassified the island status of Seil.

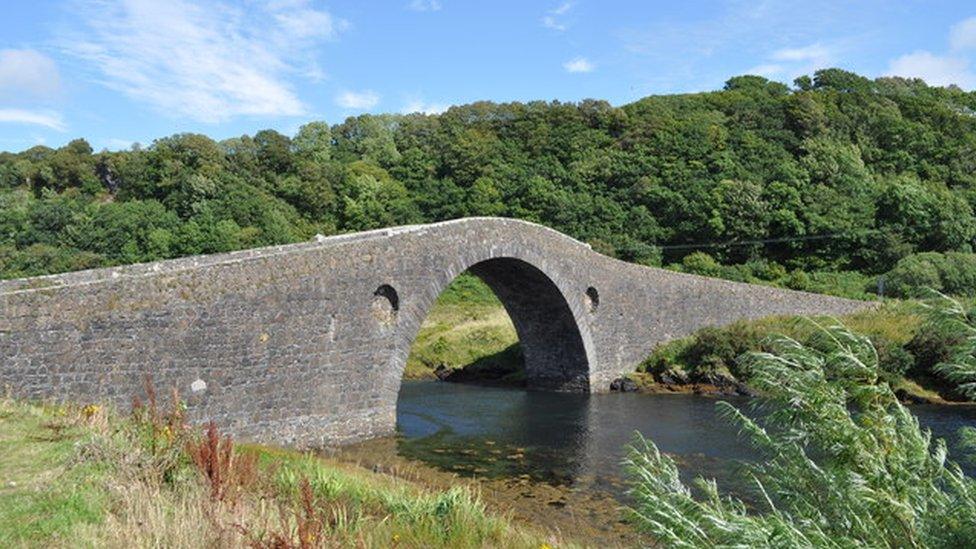

Seil has been linked to the Scottish mainland by the Clachan Bridge since 1792. The bridge is only about 22 metres long, but spans a channel linked to the ocean at both ends, leading to its nickname: "the bridge over the Atlantic".

However, in 2011 the government reviewed areas in receipt of the Special Islands Needs Allowance, and concluded that Seil no longer met the criteria - ultimately costing the local authority, Argyll and Bute Council, some £400,000 in funding.

Is Skye (left) an island, while Seil (right) is not?

Government officials justified the inclusion of Skye in the Islands Bill by citing the 2011 census, which listed 93 "inhabited islands" in Scotland.

These range from relatively heavily populated area like Lewis and Harris, Shetland and Orkney down to five tiny islands which each have a single occupant.

The census defines an island as being "a mass of land surrounded by water, separate from the Scottish mainland", and adds that: "Islands are still classified as individual islands even when they are linked to other islands or to the mainland by connections such as a bridge, causeway or ford."

This certainly describes Skye - but it also describes Seil.

In fact, the census report actually includes both in the list of 93 inhabited islands.

So far, so baffling.

The Clachan Bridge links Seil to the mainland - which has cost the local council £400,000

The answer to this conundrum lies in the specific funding mechanism disputed in the case of Seil.

The Special Islands Needs Allowance, external is designed to funnel cash to councils with needs and "characteristics unique to island communities". Some 85% of its budget goes to the three "islands councils" - in Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles.

Crucially, this fund does not apply to islands linked to the mainland by bridges - "islands with road bridge links are not eligible, as it is clearly easier to get there by road".

The government justified this in the case of Seil on the grounds that "in many cases the costs of providing public services on such islands [with bridges] will be similar to rural communities on the mainland, which are already accommodated for under the general distribution formula".

This refers to the fact that councils with a large number of islands in their local area - like Argyll and Bute, Highland and North Ayrshire - receive block funding grants per head of population above the Scottish average.

So both Skye and Seil are islands, but thanks to their bridges neither get specific islands funding.

When is an island not an island? The answer appears to be, when money is involved.

- Published13 September 2017